As humans, we have all experienced deception at some point in life. When my sister was six, she tried cutting her bangs to look more like “Belle” from Beauty and the Beast. Failing miserably, she was left to explain to our parents why her hair was cut diagonally. Ever so eloquently, she explained, “I was lying face up down in the bathtub, when a razor came out of nowhere and floated across my hair!” My parents instantly knew that she had made up the story, saving her the embarrassment of admitting her mistake. My sister, who had not put a lot of thought into her backstory, thought she could pass off a dishonest “signal” as an honest “signal”, benefiting herself while keeping the perceivers (my parents) in the dark. For similar reasons, animals in the wild have shown the ability to deceive when predation or the stress of risk is present. But in both the wild and in the household, deception is not always easy to get away. In my household, my parents knew my sister was lying because the false story (signal) was too dissimilar to the genuine one. In the wild, deception often fails when deceptive signals occur too often relative to their honest counterparts. In the wild, this poses a constraint on the degree of success when using a single, inflexible deceptive signal too often. One solution may be to decrease the frequency of deception, which would save the energy needed to produce the signal, but may cost energy when later fleeing a predator. Another solution would be to change the flexibility of the deceptive signal. If an individual could flexibly alter an aspect of the content or structure of the deceptive signal, the deceiver may get away with a higher frequency of deception. While this is an exciting idea, this flexible variation has never been observed in the wild…until…

THE FORK-TAILED DRONGO.

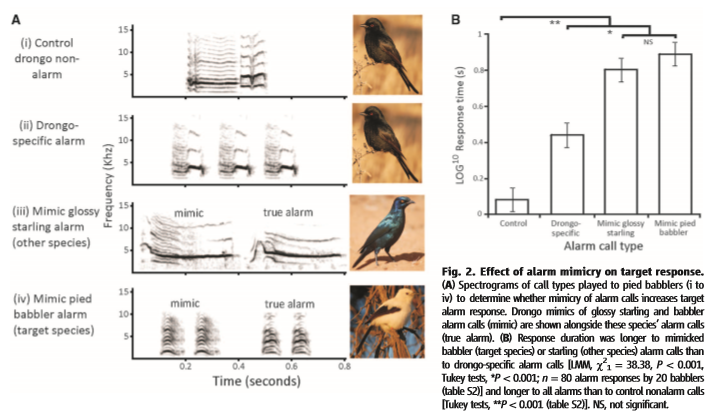

In their study published on May 2nd of 2014, Flower, Gribble, and Ridley wanted to see if fork-tailed drongos possessed the ability to differentially create alarm calls to scare and steal food away from a variety of different predators. Over the course of the research study, the 64 wild drongos observed spent over a quarter of their time following southern pied babblers and meerkats. When following these target species, the drongos would honestly produce true alarm class when they saw a predator approaching. The target species then heard this true alarm and would flee to cover in response. However, when an individual of the target species would find a large food item, the drongos produced false alarm class, causing the target to flee to cover, allowing the drongos to swoop in and steal food. But this is where it gets interesting. It turns out that the structure, and therefore perceived source (animal who truly produces it), of the false alarm changed in different scenarios. In some cases, drongos would change the duration and frequency of the alarm call to deceive the target species into thinking another animal was making the call. Therefore, the target species would see this as an honest alarm, as the “ever-deceptive” drongos was not the species producing it.

So where does this study leave us? For the fork-tailed drongos, this leads to a lifestyle full of deceit and reward. By varying their false alarm calls, drongos actually benefit in two different ways. One, they produce signals more likely to deceive their targets. Two, they avoid target habituation to repeated use of the same deceptive signal! In other words, they are tricking their target species with better accuracy, more efficiently, and over a larger period of time! But it isn’t all good news for the fork-tailed drongo. As the authors mentioned, “flexible variation might not maintain deception indefinitely because deceived species ma ultimately habituate to all the deceptive signals in their repertoire.” So the deceived species may eventually catch on in time, learning all the different ways drongos make false alarm calls. This leads to an interesting question to consider, and possible field of future study. Do fork-tailed drongos have the ability to create and mimic novel species? Can a fork-tailed drongos hear a novel alarm call and reproduce it with enough practice? Is this proof of theory in mind in birds?

Source: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/344/6183/513.short

Flowers, T.P., Gribble, M., and Ridley, A.R. (2014) Deception by Flexible Alarm Mimicry in an African Bird. Science, 344(513).