Do you remember seeing a picture of a massive animal with big ears in your fifth grade biology class? This picture was probably an African elephant! In class you discovered that African elephants are the largest land animals on Earth, weighing over 5,000 pounds and living up to 70 years. But did you know that humans represent a significant predatory threat to elephants?

Many tribes living in Sub-Saharan Africa are a significant threat to African elephants. One tribe known as the Maasai tribe comes in contact with elephants daily over grazing for their cattle and access to water. The result of the battle ends with an elephant being speared and a Maasai dead. But not all tribes pose a threat to the elephants. For example, the Kamba tribe has an agricultural lifestyle and is only worried about their crop, and their land. They are not bothered by the elephant and the elephant is not bothered by them. The age and gender of the member of the tribe also matters. Many Massai women and young boys are not involved in elephant-spearing events. So how does an elephant make a distinction between the different tribes, ages and gender to identify the most threatening individuals?

McComb and Shannon et al. (2014) answered this question by conducting a study on free-ranging African elephants in Amboseli National Park in Kenya. The researchers were trying to investigate whether elephants can use acoustic cues (voices) to discriminate between different subcategories in humans such as ethnicity, sex and age.

From March 2010 to December 2011, the scientists played recordings of Kamba and Maasai men, women, and boys to over 45 different elephant families living in Ambosli National Park. The speakers were hidden behind a camouflaged screen and the humans were asked to say “Look, look over there, a group of elephants is coming.”

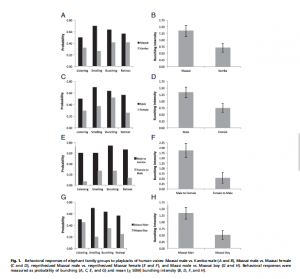

The results were recorded based off of the elephant’s reaction to the recordings. The reactions were divided into four different categories: listening after playback, investigative smelling, occurrence and extent of bunching and occurrence of retreat. The main category the study focused on was bunching.

Bunching is an elephant’s response to a situation that may be potentially dangerous to the herd. There is evidence of bunching in an elephant herd when the individuals cluster together with the young in the center and the adults facing outwards toward the threat.

From the Results in Figure 1, the elephant groups demonstrated more bunching and investigative smelling when presented with playbacks of Maasai men voices compared to Kamba men, Maasai women and Maasai boys. The scientists also compared behavioral responses of the elephant family when the voices of Maasai male and female were resynthesized. A resynthesized voice means a male voice becomes a female voice using a computer program known as a natural voice stimuli. The data shows that the elephants respond more to the male voice of the original speaker.

Overall, the results of this study show that elephants can make distinctions between voices that are associated with the level of threats between human subgroups. There are significant energetic costs for the antipredator behavior in elephants such as reduced foraging, increased locomotion and elevated stress. The ability for the elephant to decipher between human voice cues, allows the elephant to save their energy for more threatening predators such as lions and have increase fitness benefits.

So the next time you are in the middle of Sub-Saharan Africa near an elephant, be careful what you say, because the elephant can hear you!

If you would like to read this article you can find it on the website for Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

McComb, K., Shannon G., Sayialel K. N., Moss, C., (2014) Elephants can determine ethnicity, gender, and age from acoustic cues in human voices. PNAS 2014 : 1321543111v1-201321543.