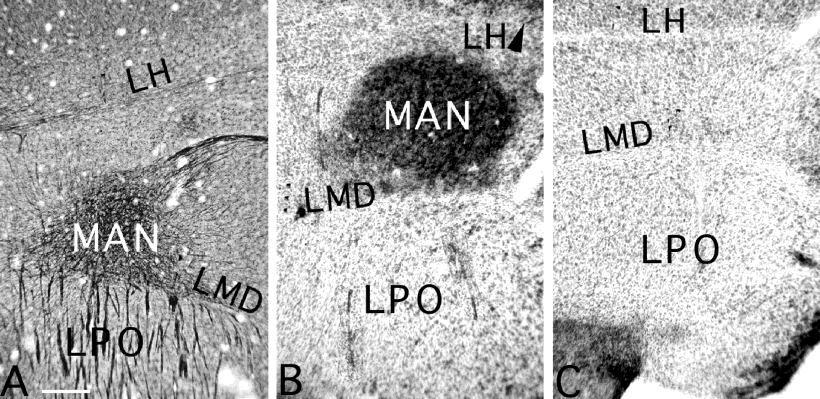

The ruby-throated hummingbird is one of the hummingbird species that does not sing. When compared to male Anna’s hummingbirds and male Amazilia hummingbirds, which do sing, the brain areas, such as the RA, HVC and LMAN, of the male ruby-throated hummingbirds are more similar to that of female songbirds like the female zebra finch rather than their male counterparts. As shown in the figure below the LMAN of the male ruby-throated hummingbird (C) does not have the dense fibers, shown in black, of the other male song birds (A,B)

Figure 1: Here is the LMAN area of the brain in a male zebra finch (A) a male Anna hummingbird (B) and a male ruby-throated hummingbird (C). By the process of fiber staining, you are able to see the darker dense areas of the LMAN more clearly. In such areas of the zebra finch and the Anna hummingbird you can see the dense plexus but this is not so for the ruby-throated hummingbird. This indicates one difference between male songbirds and male non-singing birds and supports brain development as a key factor for song learning.

Fig. 1 Source: Gahr, M., 2000. Neural song control system of hummingbirds: Comparison to swifts, vocal learning (songbirds) and nonlearning (suboscines) passerines, and vocal learning (budgerigars) and nonlearning (dove, owl, gull, quail, chicken) nonpasserines. Journal of Comparative Neurology 426: 182-196.

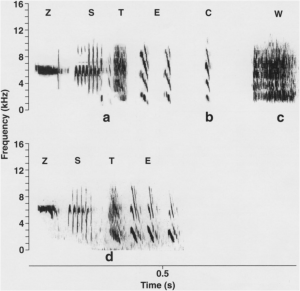

While the ruby-throated hummingbird may not sing, it does have a complex call. The call can be made up of some or all of the following six note types: Z note, S note, T note, E note, C note and W note. The Z note shown below in figure 1(A) are two narrowband frequencies and the slope at the end causes a zzzip sound. It is typically the longest note in the hummingbird’s call. The S note is usually fused with another note sometimes the T note. As with most of the other notes in the sequence this fusion of different notes creates the complexity in the hummingbirds call. The T note makes a click sound and is always fused with another note in the sequence. Likewise for E note in that it also is heard fused with other notes in the sequence. While similar to the E note, the C note is usually found at the beginning of a call w/o being attached to other notes. It can be heard as a single note or in a set of doublets or triplets. The W note the most unique note of all occurs the least of all the notes but is the longest when compared to the other notes of the hummingbird’s call. The sound resembles white noise or a zeep.

If you would like to hear the calls of the ruby-throated hummingbird click here:

Figure 2. A spectrogram of a ruby-throated hummingbird’s call. The first note shown (the Z note occurs most frequently) W note depicted at the end is usually made by the winner of an aggressive attack.

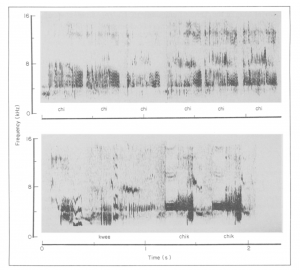

Figure 3. Spectrogram of a Anna hummingbird. It is more complex than a ruby-throated hummingbird call but some similarities, such as the W note at the end, can be seen between the two vocalizations.

Fig. 2 Source: Rusch, K.M., Thusius, K., Ficken, M.S. 2001. The organization of agonistic vocalizations in Ruby–throated Hummingbirds with a comparison to Blackchinned Hummingbirds. Willson Bulletin 113: 425-430.

Fig. 3 Source: Goldberg, Ewald, P.W. 1991. Territorial song in the Anna’s hummingbird, Calypte anna: costs of attraction and benefits of deterrence. Animal Behavior 42: 221-226.

Song Behavior

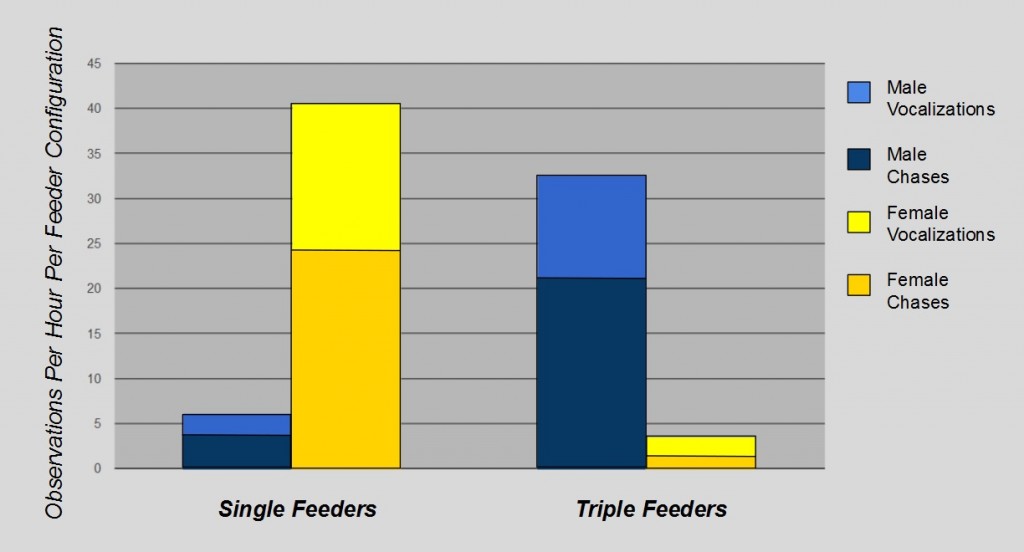

It has been observed in ruby-throated hummingbirds that aggressive behavior is often displayed after bird calls are enacted. The calls are typically described as agonistic, meaning aggressive or combative behavior towards members of the same species. In the experiment with data shown below, a single and a triplet feeder were set up and the number of vocalizations were recorded. When one bird approaches another at a feeder it was observed that the bird of residence, the bird originally at the feeder, calls first and the two continue to call at each other or sometimes chase until one bird retreats the feeder. The winner of this vocal dispute on average is the bird of residence. If two birds simultaneously arrive at the feeder, they both call and hover until one cedes possession of the feeder.

Figure 4. The average number of interactions by both male and female ruby-throated hummingbirds at single and triple feeders. On triple feeders males tended to have more vocalizations than females due to their territorial behavior around food resources.

Fig. 4 Source: Biswas, E., Dollison, C., French, J., Roos, E., 2014. The Effects of Resource Availability on Territorial Behavior of the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris) Biological Station University of Michigan (UMBS) http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/109734

This territorial aggression was looked at in further detail in terms of hormones. Hummingbirds have small bodies and with that high metabolic rates. In order to fuel their high metabolism, hummingbirds need to remember the best locations for food resources. In turn this, need for food/energy, leads them to become very territorial over food resources. The cost of aggression is taken into account, however, if that cost does not outway the need to for food, attacks such as chasing and vocalization will occur between male hummingbirds. Evidence supports that territorial hummingbirds have higher levels of DHEA during non-breeding season and the link between aggression and DHEA is shown to have a positive correlation. During breeding season testosterone was surprisingly correlative with territorial aggression. Female hummingbirds did not display the same levels of hormone variance or aggressive territorial displays yearlong.

Source: González-Gómez, P.L., Blakeslee, W.S., Razeto-Barry, P., Borthwell, R.M., Hiebert, S.M., Wingfield J.C., 2014. Aggression, body condition, and seasonal changes in sex-steroids in four hummingbird species. Journal of Ornithology 155: 1017-1025.

Future Research

Further exploration is needed in the subject of wing sound of the ruby-throated hummingbirds. While observations of hovering have been made in relation to competition over resources, sufficient evidence is needed to support the reasons why one hummingbird deters while the other remains at a food source location in relation to the sound the wings make while hovering. Also studies in wing sounds in comparison to mating have not been conducted in detail. The wing hum in tandem with agonistic vocalizations would help support the hypotheses for why ruby-throated hummingbirds and other non-singing hummingbirds can be territorial without complex vocalizations. In order to obtain these results, an observational experiment could be set up in which you have a hummingbird feeder that would insight aggressive competition for the food resource and the wing sounds at various points of the aggression can be recorded. The time spent hovering could also be observed and taken into account as a possible variable effecting the level of aggression. We could also set up a manipulative experiment in which we would band and capture male and female ruby-throated hummingbirds and record the males aggressive behavior overtime. In a lab setting we can closely observe how many mates they receive and compare it to something involving wing sound such as the length of time spent hovering during aggressive attacks.

Bibliography

Biswas, E., Dollison, C., French, J., Roos, E., 2014. The Effects of Resource Availability on Territorial Behavior of the Ruby-Throated Hummingbird (Archilochus colubris). Biological Station University of Michigan (UMBS) http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/109734

Gahr, M., 2000. Neural song control system of hummingbirds: Comparison to swifts, vocal learning (songbirds) and nonlearning (suboscines) passerines, and vocal learning (budgerigars) and nonlearning (dove, owl, gull, quail, chicken) nonpasserines. Journal of Comparative Neurology 426: 182-196.

Goldberg, Ewald, P.W. 1991. Territorial song in the Anna’s hummingbird, Calypte anna: costs of attraction and benefits of deterrence. Animal Behavior 42: 221-226.

González-Gómez, P.L., Blakeslee, W.S., Razeto-Barry, P., Borthwell, R.M., Hiebert, S.M., Wingfield J.C., 2014. Aggression, body condition, and seasonal changes in sex-steroids in four hummingbird species. Journal of Ornithology 155: 1017-1025.

Rusch, K.M., Thusius, K., Ficken, M.S. 2001. The organization of agonistic vocalizations in Ruby–throated Hummingbirds with a comparison to Blackchinned Hummingbirds. Willson Bulletin 113: 425-430.

the sound so clearly! is that you called it song?