Posted on behalf of Ron Patkus, Director of Archives and Special Collections

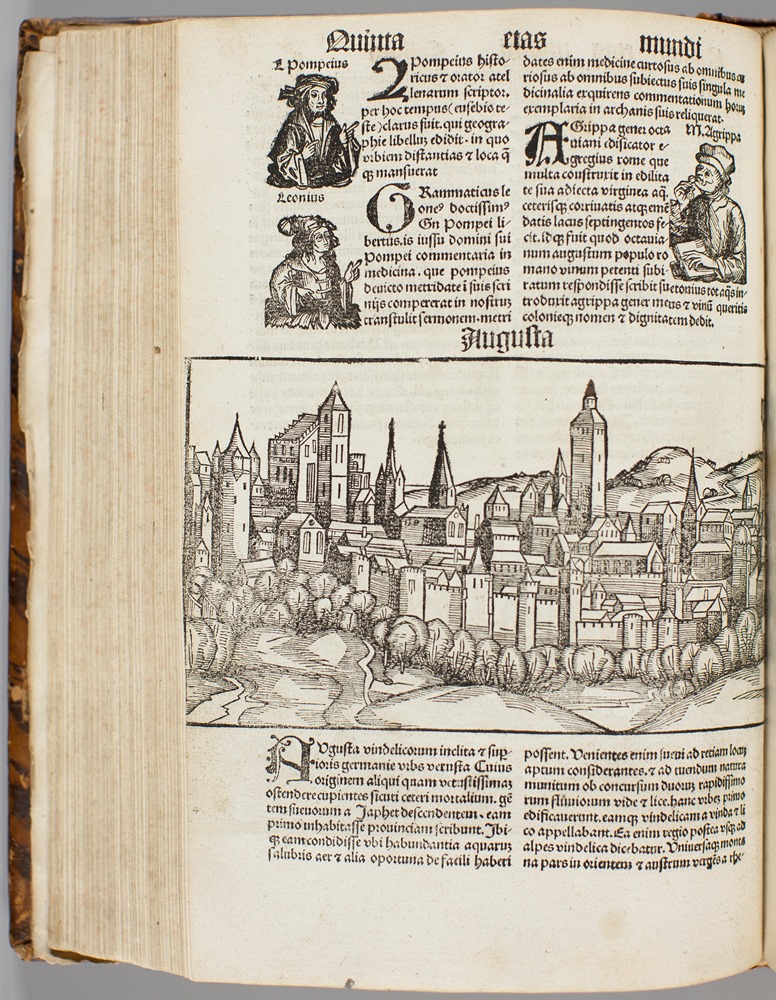

On view in the Vassar College Library this semester is “Never Before Has Your Like Been Printed: The Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493.” This exhibition deals with the most heavily illustrated book of the 15th century. Compiled by the German humanist Hartmann Schedel, illustrated by Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff, and printed by Anton Koberger, this folio-sized work presents a history of the world, beginning with the story of creation. Amazingly, the Nuremberg Chronicle features more than 1,800 woodcuts of people, cities, and events. Vassar is fortunate to count among its holdings both Latin and German editions of the book, which came out in the same year. In addition, it has a number of leaves from the two editions, as well as books that relate to the Nuremberg Chronicle in some way.

Because of its important place in the history of printing, many people have at least some knowledge of this famous work. Less well known is the story of the “pirated” editions of this work. In 1496, a printer by the name of Johann Schönsperger (c. 1455-before 1521) produced copies of the German text in Augsburg, a city about 90 miles south of Nuremberg. The next year he printed a Latin edition, and then in 1500 he again printed the German edition. Schönsperger’s editions followed the text of the Nuremberg originals closely, but they were smaller, with newly-made illustrations. They were therefore cheaper and more portable than the Nuremberg originals, and so aimed at a different audience.

Vassar holds a copy of the 1497 Latin edition that was printed in Augsburg, and it is on display in the current exhibition. This copy bears interesting marks of its history. We see, for instance, several inscriptions and ink stamps of previous owners on the title page, and a bookplate on the front paste-down for the most recent owner, George McMaster Jones. In addition, there are early marginal annotations throughout, including some relating to Pope Joan, with an expanded account of her life tipped in before leaf 191. The book is bound in 17th century sheep, with a decorated spine. Apart from this book, Vassar also owns a leaf-book, which tells the story of the Nuremberg Chronicle and includes a leaf from a copy of the same Latin Augsburg edition.

The story of the Augsburg printings tells us much about early printing in Europe. It’s interesting to see how Koberger and Schönsperger each tried to package and market a particular work in ways they felt would be profitable. Koberger may not have anticipated that other printings would be made so soon, and Schönsperger’s efforts almost certainly cut into the sales of the Nuremberg originals (we know from a 1509 accounting that nearly 600 copies of Koberger’s books were left unsold). In addition, the production and circulation of the Augsburg printings also tells us something about how popular this text was at the end of the fifteenth century. If we add up the copies sold from printings in both cities, we see that the texts circulated widely across the continent. Knowing something about the “other” Nuremberg Chronicle gives us a much fuller picture of this remarkable work.