Between a Rock and a Hard Place

Geological Illustration from Catastrophism to the Anthropocene

An Exhibition at the Vassar College Art Library

October 5 to December 20, 2018

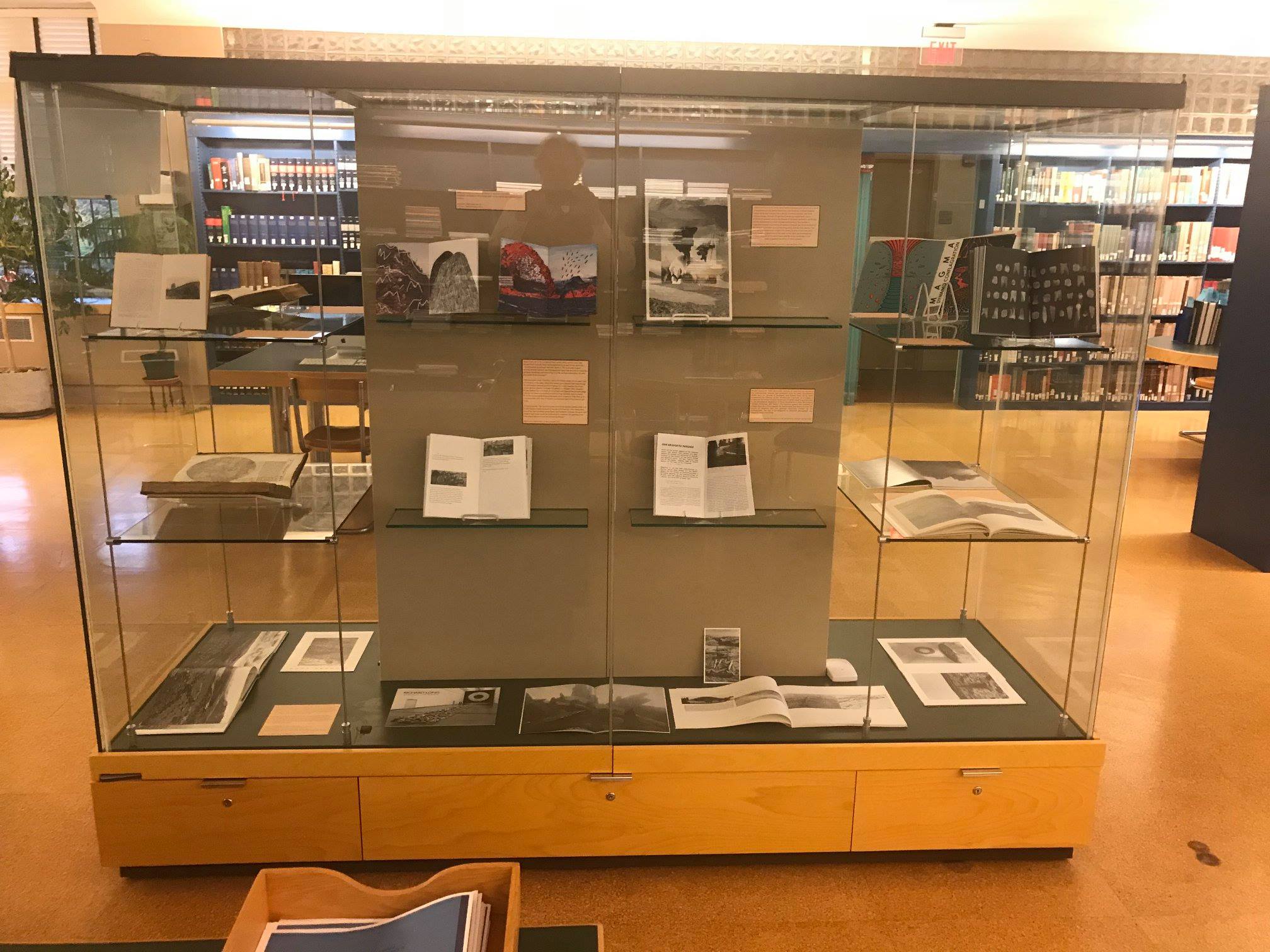

Our exhibit begins with the 1697 English edition of Thomas Burnet’s Theory of the Earth, opened to an engraved image of a view of the Earth at the receding of the waters of the great Deluge described in Genesis 6-9, showing a tiny Noah’s Ark grounded on Mount Ararat at the center, and, according to the author’s theory, Earth’s newly formed continents and mountain chains just visible under the waves. As an example of illustration we would consider the image today to be more fanciful than scientific, based on scriptural sources, since we believe today that most familiar landforms developed through time very gradually and not by catastrophes and cataclysms, divinely caused or natural, such as floods and volcanoes. The image, however, is emblematic of a number of natural histories illustrated by contemporary interpreters of the science and history of our planet, including the artists whose works appear elsewhere in this exhibit.

Detail of an illustration concerning the composition of the crust in the Paris’ basin, from Cuvier’s and Brongniart’s study.

Noah’s Ark, whose etymology (Old English ærc, from Latin arca, chest) describes a closed box or tabernacle (as in the Ark of the Covenant), denotes as well a box for keeping records. It is related to our word “archive,” and is symbolic of the impulse toward archivism that characterizes so many of the books displayed here. George Cuvier, the founder of paleontology, for instance, in his own Theory of the Earth (1818) presents the Earth itself as an archive of ancient activity as well as of living and extinct life forms, organized temporally in layered strata, which binds geologic science through the fossil record to biological history.

Eurypterus (sea scorpion) fossil. Courtesy Scott Warthin Museum of Geology and Natural History, Vassar College

The ark of the Earth itself therefore transports and discloses to us across great spans of time information about events and species that time and the Earth have both swallowed up, including, as Darwin would eventually surmise, our own ancestry.

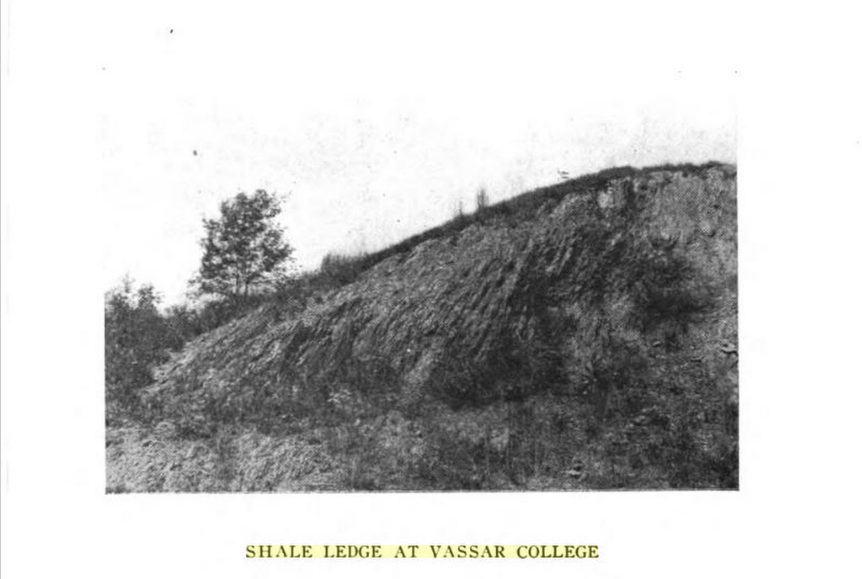

The close alliance between artistic illustration and geologic theory and documentation examined in the Frances Lehman Loeb Art Center exhibition Past Time: Geology in European and American Art, which this exhibit accompanies, was facilitated from the middle of the Nineteenth Century, as was all scientific recording, with the invention of photography and the adoption of the photographic document. George Shattuck, a Professor of Geology and Mineralogy at Vassar College at the beginning of the Twentieth Century, bolstered his own geologic exploration and teaching by becoming an early adept and proponent of this medium, deployed here for educational purposes in his photographic guide, Geological Rambles Near Vassar College, (1907). Besides his use of photography as an archival medium, Shattuck’s descriptive rambles signal another feature embodied in Burnet’s account of Noah’s Ark, that of the “story” in “natural history,” or the use of narrative for recording past events. Most of the remaining artists’ books in our own “ark” (our Art Library exhibit case was originally designed for displaying scientific specimens) investigate both types of documentary media: storytelling and the photograph.

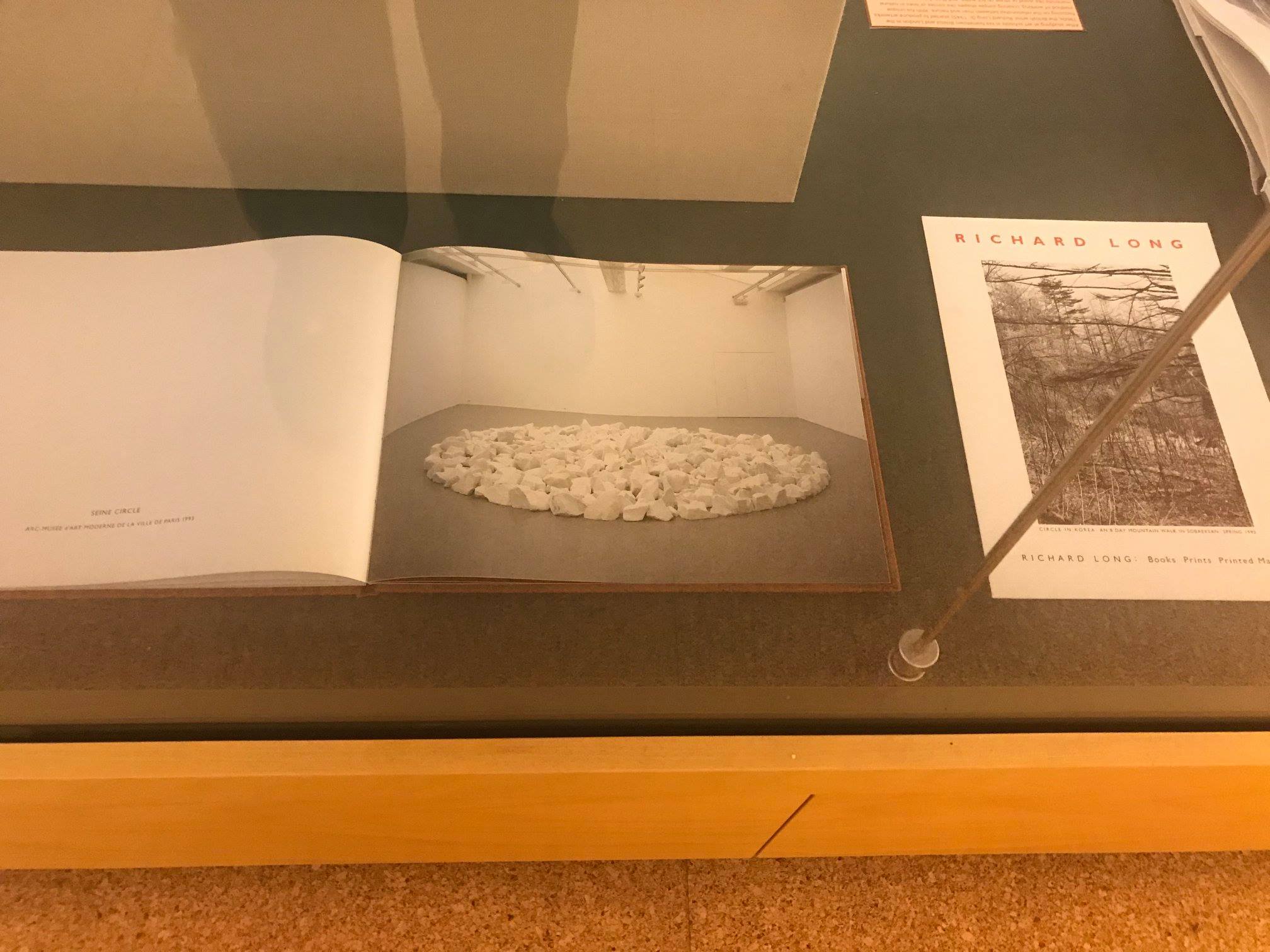

Most prominent here for examples of itinerant narrative and photography both are the publications of the British artist Richard Long, whose work is comprised of photographic and sculptural records of his own rambles across landscapes and his interventions therein. Eight of his books are exhibited here along the bottom of the exhibit case (1984-2001).

Long is keenly interested in the role of human activity on the memorial record of the Earth, and he may be viewed as an early interpreter of the concept of a new era characterized by human impact on the Earth’s geology and ecosystems, designated popularly as the Anthropocene.

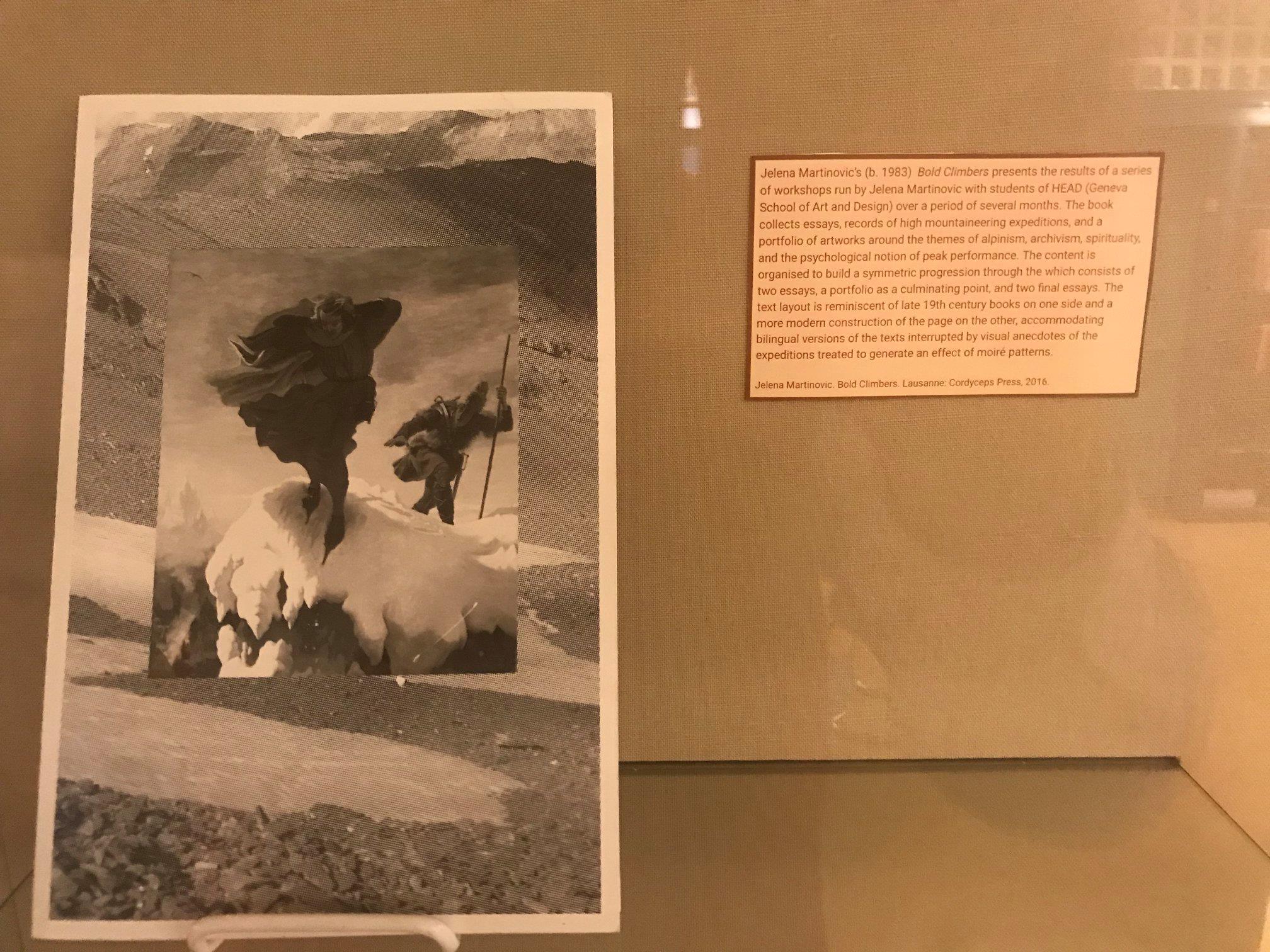

Other artists here whose works examine the tools of narrative and photographic documentation include Swiss-born Jelena Martinovic’s historically-inclined tribute to mountaineers, Bold Climbers (2016),

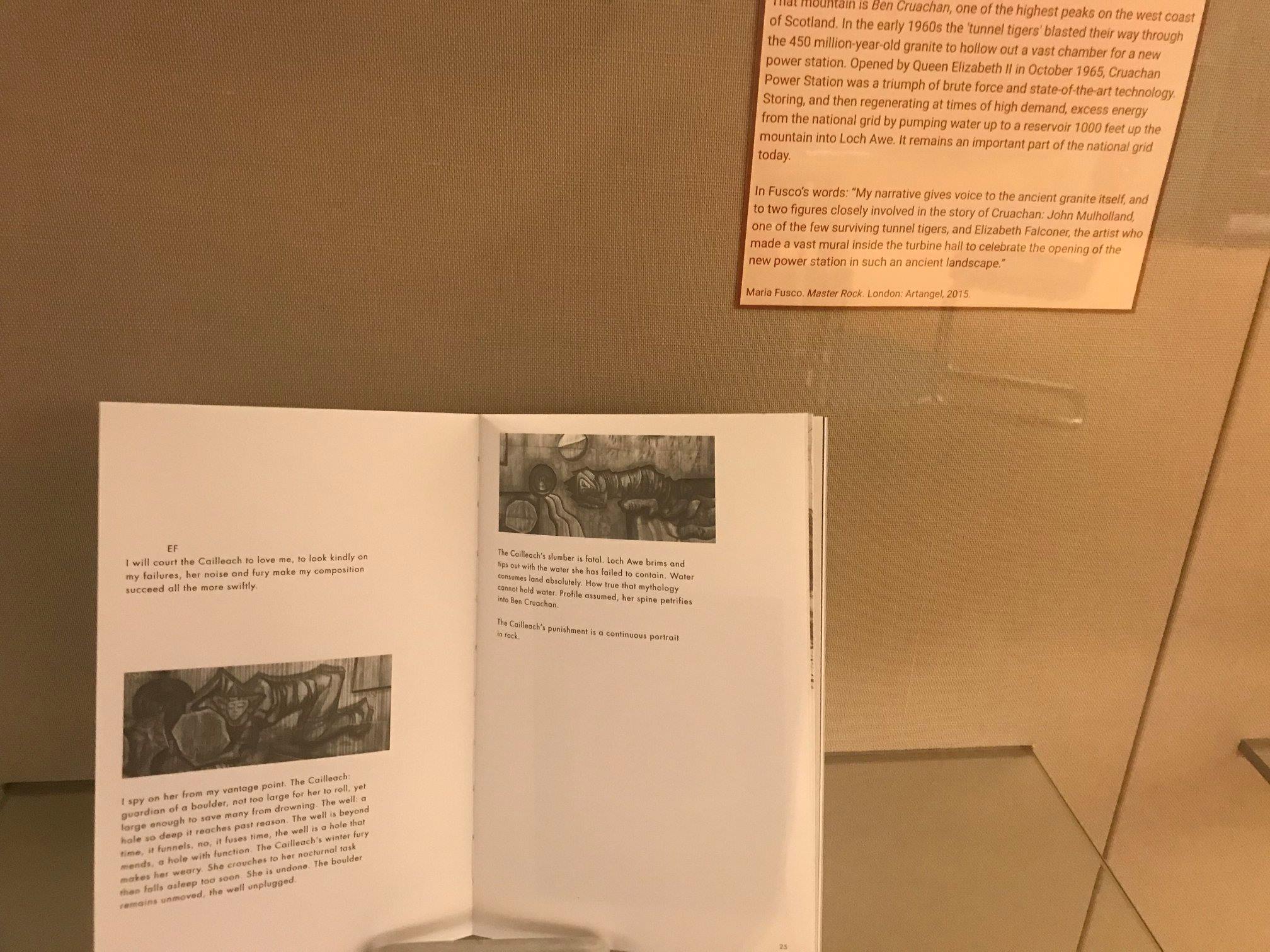

Belfast-born Maria Fusco’s myth-tinged book documenting the building of the Cruachan Power Station, Master Rock (2015),

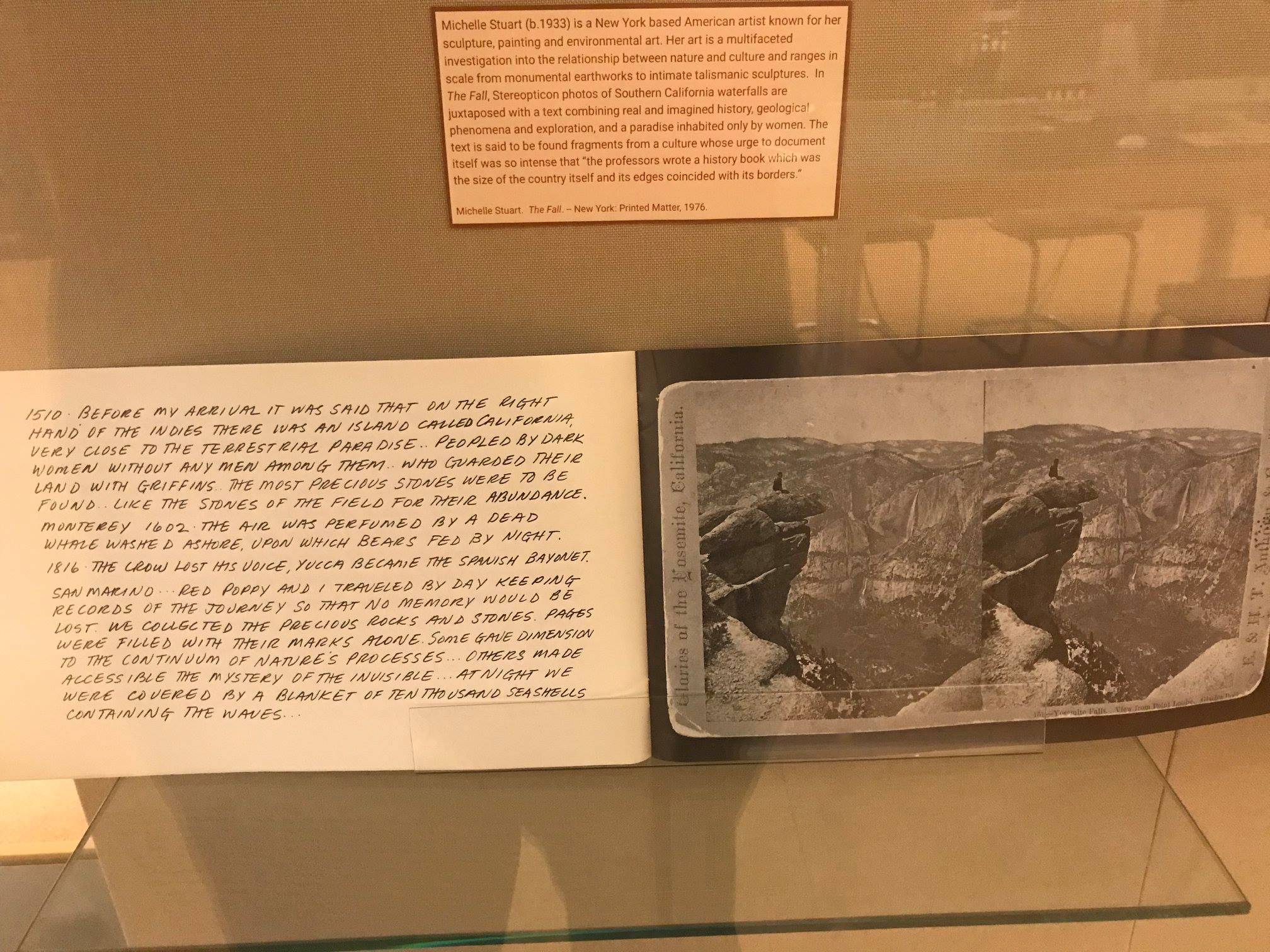

Michelle Stuart’s fanciful history of a California inhabited only by women, The Fall (1976),

and the Norwegian artist Kurt Johannessen’s talismanic and anthropomorphizing Steiner (2002), who recites stories not about rocks but to rocks.

Like Johannessen’s Steiner, Luke Stettner’s artist’s book History Database (2016) is an archive that blurs the distinction between the living or once-living, and non-living aspects of the geologic record. Like Martinovic, Fusco, and Stuart, Stettner employs archival photographs and illustrations, along with new photography, drawings, pictograms and photocopies to tell a larger story about mortality, documentation, and deep time.

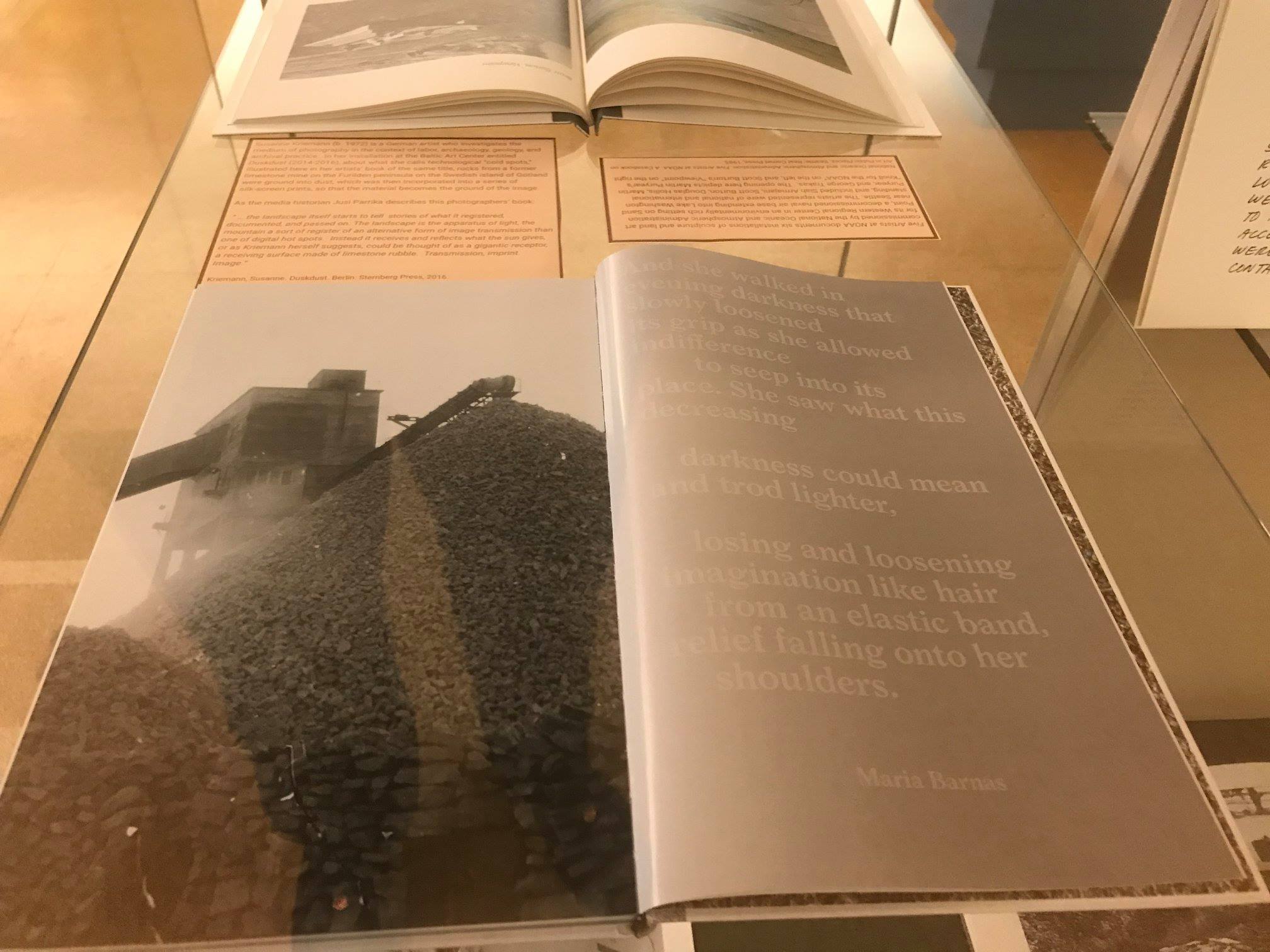

Most interesting in her exploration of the Earth, archives, narrative, and photography, in her work Duskdust (2016), the Berlin-born artist Susanne Kriemann creates documents from the material of the Earth itself in the stark light of what is sometimes referred to as the “bunker archaeology” of the Anthropocene. Her silk screens incorporate paper made from ground limestone from the abandoned quarry on the Swedish island of Gotland she investigates, while her photographs capture the natural light of the quarry at various times of day, relating these by association to narrative texts and archival materials, including old photographs.

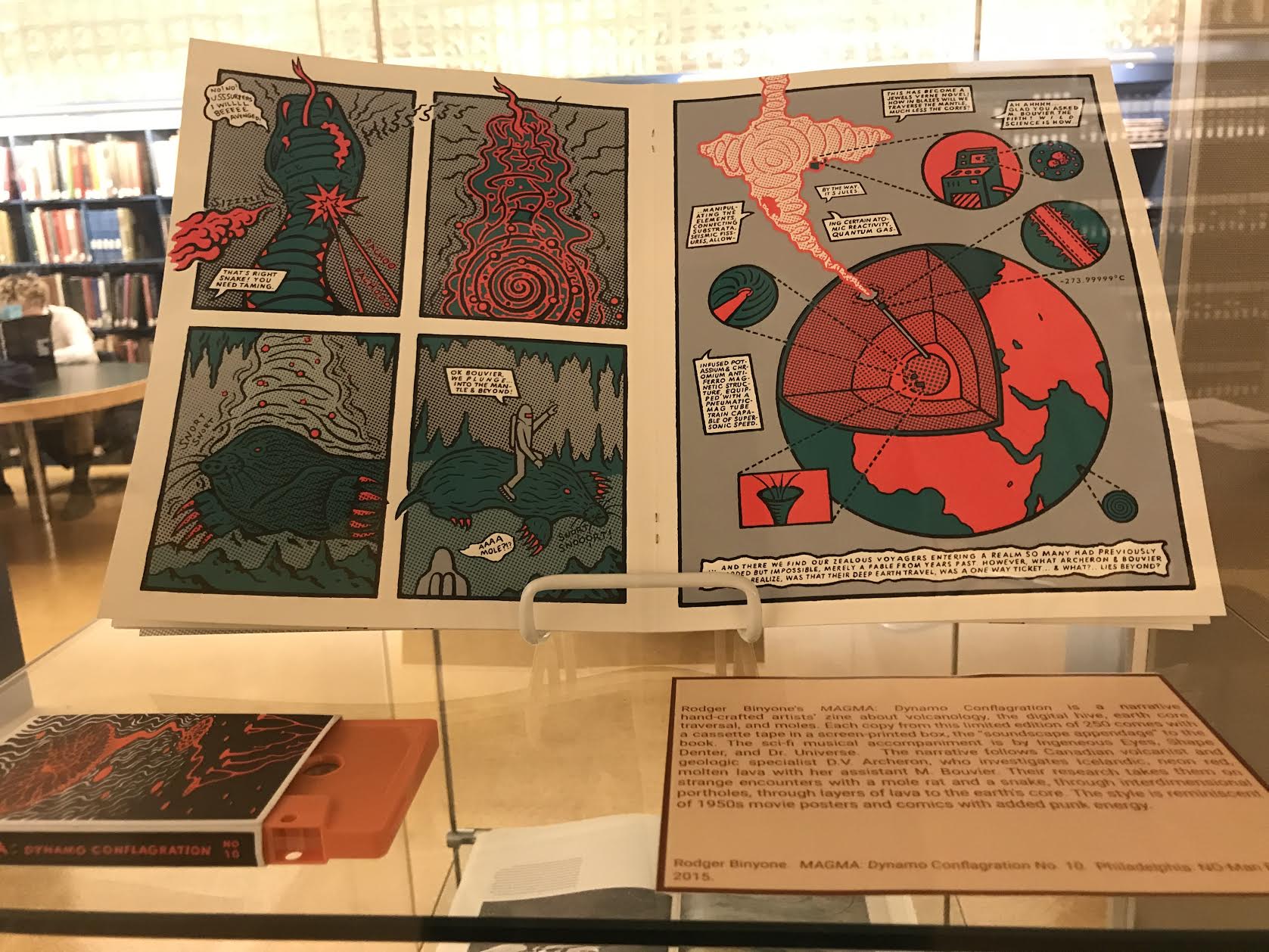

Not all of our contemporary illustrative interpreters of the Earth are photographers. The graphic (from the Greek graphos, to write, carve, or dig) artist Rodger Binyone’s colorful artist’s book MAGMA: Dynamo Conflagration No. 10 (2015), is a fanciful narrative based loosely on Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth (very loosely), about a Canadian volcanist and her assistant’s quest, aided by a mole rat, into the Earth’s core in search of a special neon-red Icelandic magma.

Brooklyn-based Sibba Hartunian’s books Volcanoes and Mountains are colorful multiples issued and sold inexpensively in small numbers, produced through environmentally-friendly risograph printing (employing a soy-based gelatin), enlisting the artist’s process in limiting the disruption done to the Earth by human intervention.

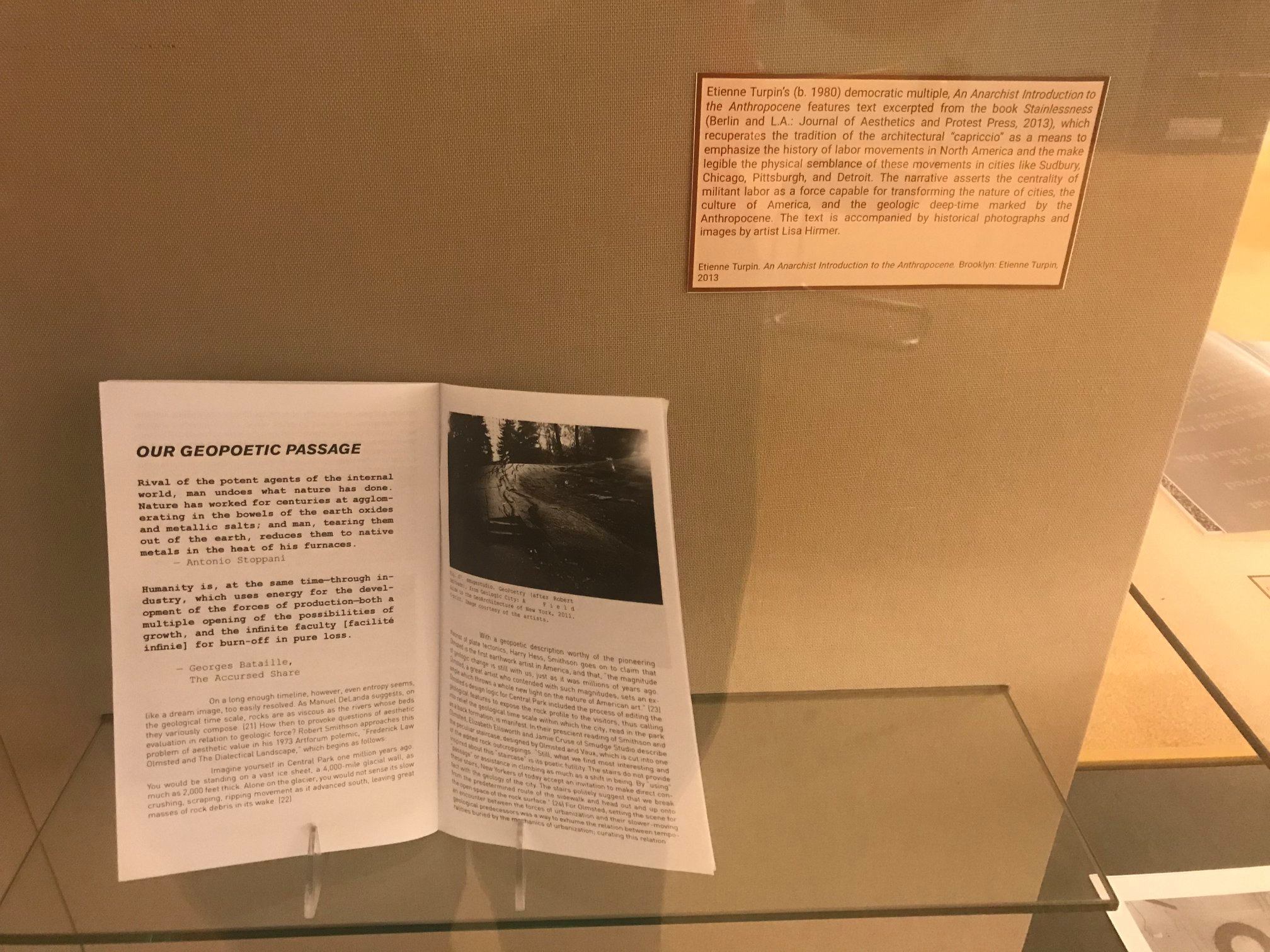

Also addressing the damaging effects of humanity on the Earth characteristic of the Anthropocene is Etienne Turpin’s An Anarchist Introduction to the Anthropocene (2015), which brings to bear a narrative asserting the “centrality of militant labor as a force capable of transforming the nature of cities, the culture of America, and the geologic deep-time marked by the Anthropocene.”

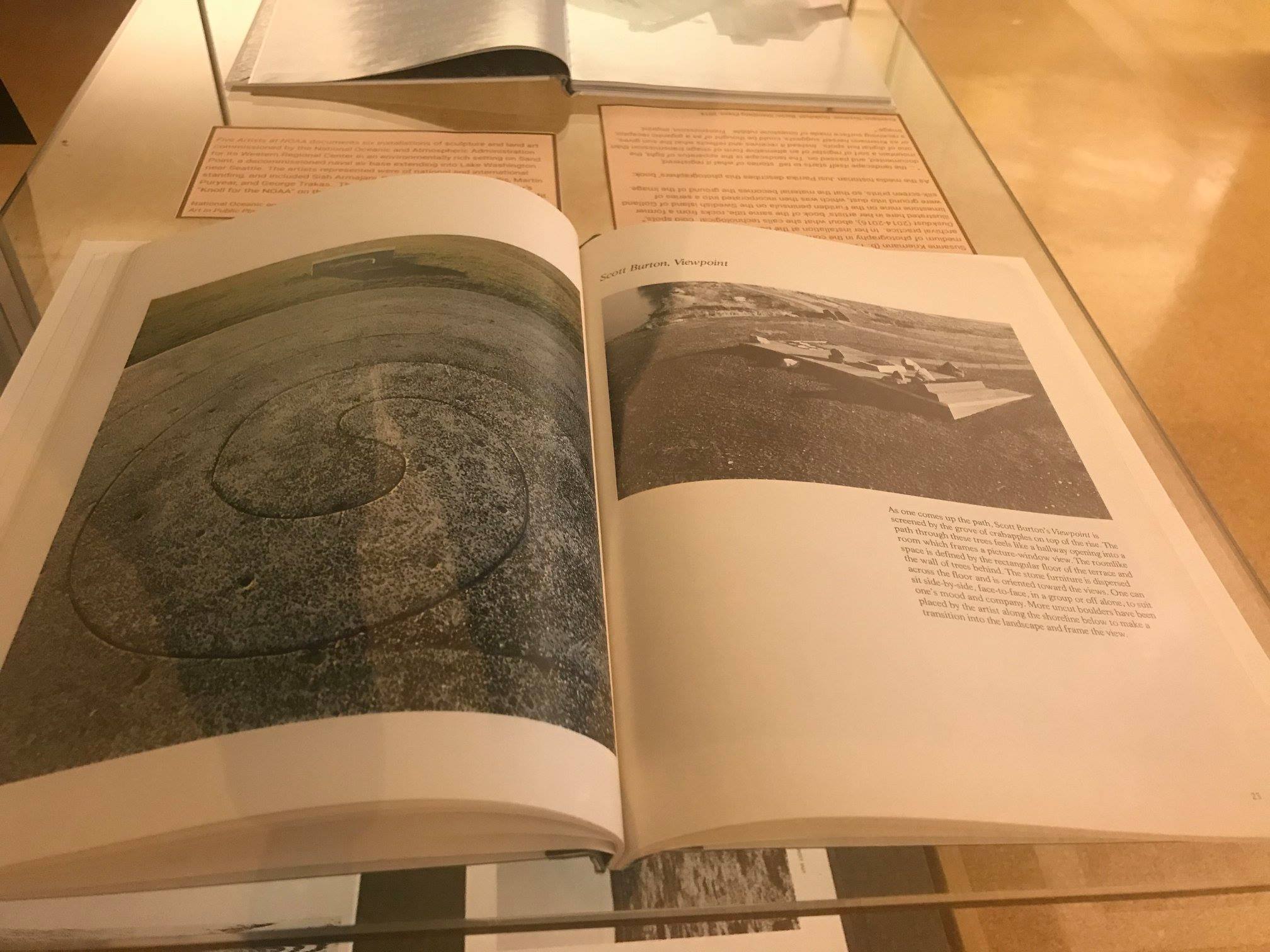

Positive approaches to our relationship with the Earth are also apparent in certain institutional or governmental competitive projects that meld earth science and art. These are represented here by the NOAAs (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) Western Regional Center at Sand Point, Washington in the land art featured in Five Artists at NOAA: A Casebook on Art in Public Places (1985);

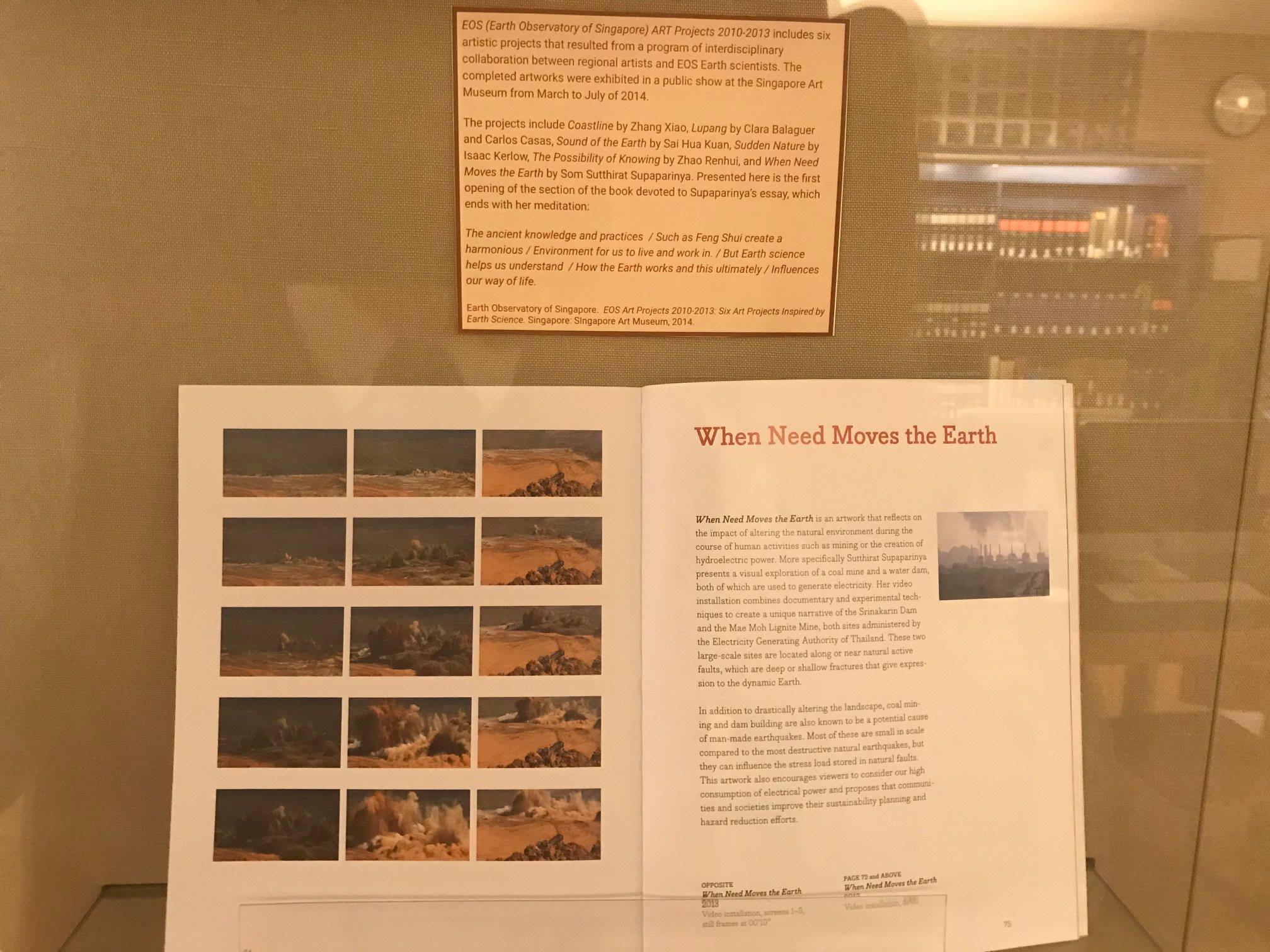

and EOS (Earth Observatory Singapore: Art Projects 2010-2013: Six Projects Inspired by Earth Science (2014).

Finally, in her acclaimed Queens Museum exhibition of last year, Wandering Lake (2017), documented in her artist book of the same name, Patty Chang offers a geologic, archival, and photographic meditation on the loss of her father and the birth of her son. Her thoughts are interwoven with a narrative inspired by the Swedish geographer and travel writer Sven Hedin, who tells a story about a migrating lake in the Gobi desert. A story of powerlessness, Chang’s statement has more to do with the function of art as a vehicle for mourning the present than its imagined role in making things better in the future. As a counterpart to the image we opened with of Noah’s Ark grounded upon the rock of Mount Ararat, the exhibit ends with the hard place of an emblematic photograph by Chang of another beached boat as she hopelessly scrubs its barnacled hull.

Checklist

Books in the Exhibition arranged by publication year:

Burnett, Thomas. The Theory of the Earth: containing an account of the original of the Earth, and of all the general changes which it hath already undergone or is to undergo till the Consummation of all things. Third Edition. – London: R.N., 1697. Loaned from the collection of Prof. Jill Schneiderman.

Cuvier, Jean Leopold Nicholas Frederick Cuvier, Baron. Essay on the Theory of the Earth with Mineralogical Notes and an Account of Cuvier’s Geological Discoveries by Professor Jameson, to added Observations on the Geology of North America. Illustrated by Samuel L. Mitchell. – New York: Kirk & Mercein, 1818. Loaned from the collection of Prof. Jill Schneiderman.

Shattuck, GeorgeBurbank. Geological Rambles Near Vassar College. -Poughkeepsie: The Vassar College Press, 1907. Loaned from the collection of Prof. Jill Schneiderman.

Stuart, Michelle. The Fall. – New York: Printed Matter, 1976.

Long, Richard. Aggie Weston’s. No. 16. – London: Coracle Press, 1979.

Long, Richard. Richard Long. – Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum Eindhoven, 1979.

Long, Richard. Postcards 1968-1982. — Paris: Union à Paris, 1984.

Long, Richard. Richard Long. – Fonds Regional d’Art Contemporain Aquitaine, 1985.

United States. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Five Artists at NOAA: A Casebook on Art in Public Places.— Seattle: Real Comet Press, 1985.

Long, Richard. Neanderthal Line, White Water Circle. — Dusseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 1994.

Long, Richard. Richard Long. — Dusseldorf: Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, 1994.

Long, Richard. Mountains and Waters. – New York: Braziller, 2001.

Johannessen, Kurt. Steinar. — Bergen: Zeth Forlag, 2002.

Turpin, Etienne. An Anarchist Introduction to the Anthropocene. – Brooklyn: Etienne Turpin, 2013.

EOS Earth Observatory Singapore. ART Projects 2010-2013: Six Art Projects Inspired by Earth Science. — Singapore: Singapore Art Museum, 2014.

Binyone, Rodger. MAGMA: Dynamo Conflagration No. 10. – Philadelphia, 2015.

Fusco, Maria. Master Rock. – London: Artangel, 2015.

Hartunian, Sibba. Mountains. – Sibba Hartunian, 2016.

Hartunian, Sibba. Volcanoes. – Sibba Hartunian, 2016.

Kriemann, Susanne. Duskdust. – Berling: Sternberg Press, 2016.

Martinovic, Jelena. Bold Climbers. – Lausanne: Cordyceps Press, 2016.

Stettner, Luke. History Database. – SPBH Editions, 2016.

Chang, Patty. Wandering Lake. – New York: Queens Museum, 2017.

Curated by Thomas E. Hill, Art Librarian

Poughkeepsie: Vassar College, 2018.