Sutematsu Yamakawa was born February 23, 1860, in northeastern Honshu, the largest of the four main islands of Japan. Twelve years later, Sutematsu (sometimes referred to by the Anglicized and more phonetical “Stematz”) became one of five young women to arrive in the United States with the Iwakura Mission, a diplomatic group from Japan’s

new Meiji government sent abroad to strengthen political ties and educate Japan’s leaders regarding western modernization. The five girls, aged 6-14, were to spend ten years in the United States then return to their country to become exemplary mothers in a modern Japan.

Shortly after her arrival in the United States in 1872, Yamakawa was placed with the family of Rev. Leonard Bacon in New Haven, Connecticut. Yamakawa spent the remainder of her childhood with the Bacons, becoming a cherished member of the family and best friend to youngest daughter Alice. After graduating from Hillhouse High School, Yamakawa was accepted at Vassar College, as was Shige Nagai, another student from the Iwakura Mission. Both were popular and did well academically. Nagai, who later became the Baroness Uriu, studied for three years as a Special Student in music. Yamakawa was president of her class, an active member of many clubs, and graduated with honors in 1882. She was the first Japanese woman to receive a college degree.

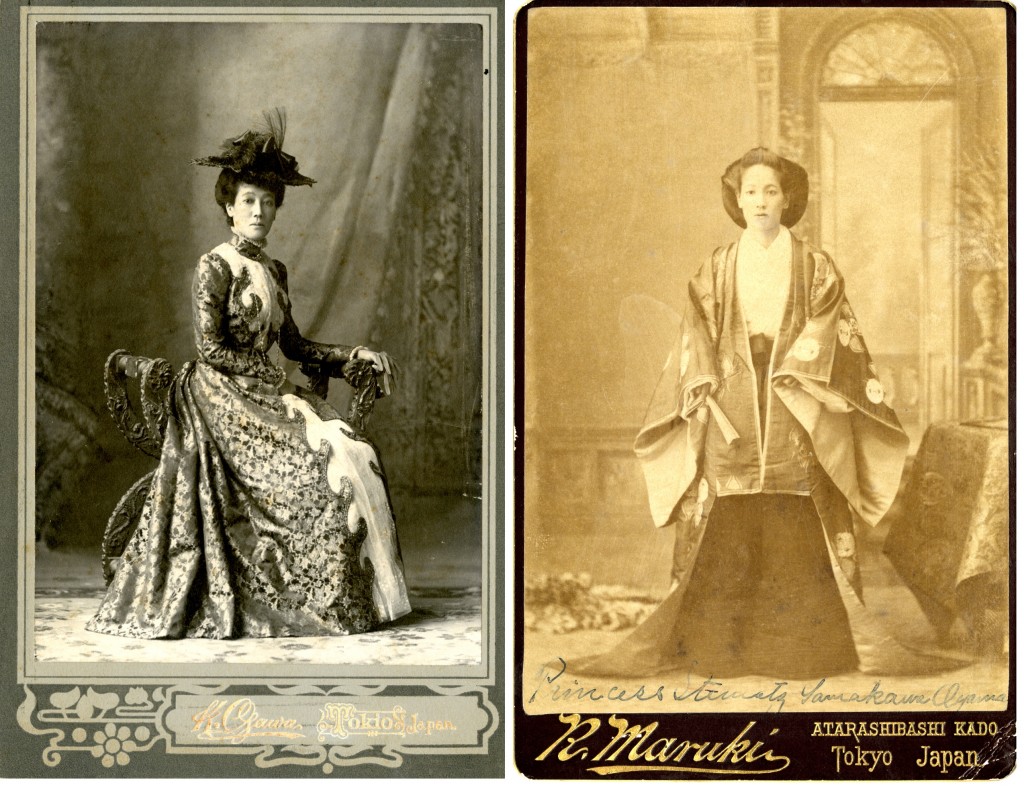

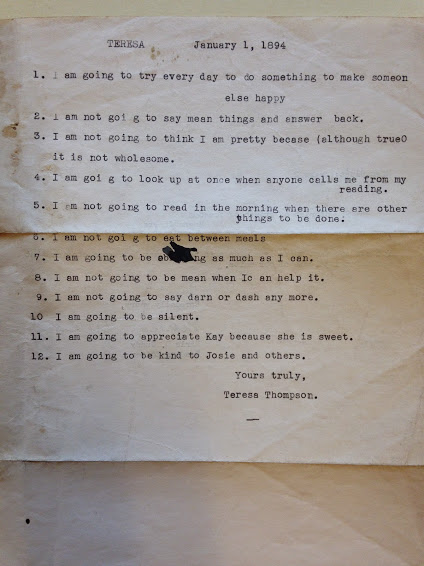

After Vassar, Yamakawa briefly attended nursing school in New Haven, but soon returned to Japan. She searched for teaching or government work, but because she could speak Japanese but had never learned to read or write the language, her job prospects were dim. Marriage seemed her only option. In 1883, she married Iwao Oyama, a 42 year old widower, father of three, and the Japanese Minister of War. After her marriage and a series of promotions for her husband, Sutematsu Yamakawa became Countess Oyama, and later, Princess Oyama. She took on roles common to government officials’ wives, but also met with the Empress to give advice on western style and customs, encouraged upperclass women to volunteer as nurses (previously considered a menial occupation), and furthered the cause of women’s education as a trustee of the Peeresses’ School in Tokyo and co-founder of the Girl’s English Institute (Joshi Eigakujuku). In 1919, Sutematsu Oyama fell victim to the influenza epidemic that swept Tokyo. She died just five days short of her sixtieth birthday.

This biography was taken from the Guide to the Sutematsu Yamakawa Oyama Papers in the Archives & Special Collections Library.