By Sofia Benitez and Alex Raz

Creatives are forever fascinated, tormented, and curious alike of what the world has to offer, and thus are constantly engaging in disciplines that isolate or explain certain notions. And from the visual to the performance, artistic translation and abstraction of actual events into personal vision has provided material for us to discover the context of these creations.

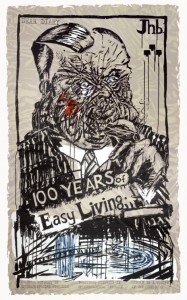

The exhibition “Tongues in Trees: Xylography and the Uses of Adversity” is curated by Art Librarian Thomas Hill. The exhibit is part of a larger series emphasizing woodblock printing. Photo By: Alec Ferretti for The Miscellany News

These “portraits” of the real and the ideal in history have allowed us to delve into the human psyche and analyze, notwithstanding limitations, the significance of certain works of art—where the environment of these works become entirely intertwined with their reception.

And so it is that, like constellations, we can trace connections that bind various reflections on human remembrances to create a boundless space of impressions.

These thoughts might all seem abstract, but appear concretely in the three ongoing exhibits at Vassar College: Tongues in Trees: Xylography and the Uses of Adversity (through December); Never Before Has Your Like Been Printed: The Nuremberg Chronicle of 1493 (through December 10); and Imperial Augsburg: Renaissance Prints and Drawings 1475-1540 (through December 14.) These displays inform each other in complementary discourses. They depict civilizations rendering realities that focus on chaos, historical narratives or cultural testimonies. With Imperial Augsburg and the Never Before… previously spoken to by Taylor and Kayla we will refer specifically to Tongues in Trees, because very unironically, it spoke to us.

Duke: Sweet are the uses of adversity,

Which, like the road, ugly and venomous,

Wears yet a precious jewel in his head;

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.

Shakespeare, As You Like It, 2.1.12-16

Tongues in Trees focuses on the art of print, woodcut and linoleum, fundamentally in the function of the medium as a vehicle to manifest experience. Frans Masereel, Werner Pfeiffer and Stanley Donwood participate in this collective diagram of the urban dimensions. Masereel, author of La Ville (1925), depicts the Europe between wars, bringing to light the realities of working class individuals and communities. He illustrates the process of facing modernity, the way in which the transition to urbanization complicated the phenomenon of human against machine–forecasting future feuds that would take a global scale. Masereel pursues an agitating geometry of animate and inanimate elements coexisting in a newfound environment; giants towering above people, herculean monuments that challenge the might of the individual, as well as striking, dynamic vignettes that play with perspective by alternating between the representation of character and setting. The polarized palette of black and white recreates the dichotomy of ecstasy and strife, elements present during the bridge between the world wars that contributed towards the tension of the Weimar period, now made tangible by the prints of this Expressionist exponent.

William Kentridge, “Art in a State of Siege,” from the triptych of the same title, 1986. Via art21.org.

The mutilated, heavily contrasted and expressionistic representations of Tongues in Trees are telling of a communal chaos that is not necessarily specific to eras or settings, but a persistent confrontation with reality. The wonder of the exhibition then is that its themes allow us to look forward from Imperial Augsburg and Never Before…, to look beyond the intricate details and self-aggrandizing portraits towards more resonant bodies and scenarios.

With this exhibition in mind, we’re also brought to think of similar artists, artists whose inward reflections on their identities and environment explore these negative spaces through printmaking—Xu Bing’s The Book from the Sky, Enrique Chagoya, Denise Hawrysio, William Kentridge, and Martin Puryear. Their works encompass a wide range: Bing’s exhibition addresses our use of language and the medium of the book itself, Chagoya complicates notions of culture and personal narrative through a historical lens, and Kentridge’s loosely inscribed layers carry with them not just an interrogation of the self, but of the political atmosphere that burdens individual lives.