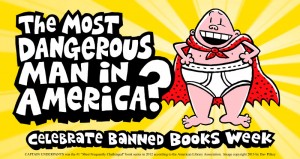

For those of you who don’t know, the supposedly dangerous man pictured here is none other than Captain Underpants. Why is a man in nothing but a red cape and underwear on your computer screen, you ask? He’s here because the entire Captain Underpants book series by Dav Pilkey ranks 13th on the American Library Association’s Top 100 Banned/Challenged Books list from 2000-2009. These and many other books have been censored for years, unjustly challenging our freedom to read. In celebration of Banned Books Week, each member of the CAAD team picked his or her favorite banned book. Read on to find out why these particular books are so important to us and we encourage you to pick your favorite banned book as well!

Kayla:

When trying to choose a banned book to write about, I had a very difficult time. The Grapes of Wrath is one of my favorite books of all time, and has been banned for its language, sexual references, and controversial implications about religion, society and politics. The Harry Potter series was an integral part of my childhood, yet has been banned in several schools and towns for the concepts of magic, witchcraft and wizardry conflict with Christian ideas. The banned book that has had the most impact on my life, however, as both a reader/writer and a person in general, is Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird (1962).

I was in seventh grade the first time I read To Kill A Mockingbird. At this point in my education, my literature classes still revolved around guided reading groups, each group choosing a different book to have small discussions about each week. About halfway through the year, the day we were to choose our next reading group text, my teacher held up a copy of To Kill A Mockingbird, telling us that, though it was a difficult read, she thought that many of us could handle reading it, myself included.

When she first labeled the novel “difficult,” I assumed she was solely speaking to the book’s more sophisticated language and complicated traits certainly are characteristic to the novel; however, I now realize that my teacher also meant that the subject matter itself was difficult.

After completing the book in seventh grade, my first emotional response was a sense of accomplishment. To Kill A Mockingbird was the first literary classic that I had read, and I felt for the first time that I was really maturing as a reader and engaging in “real” literature. This did not completely take away from the difficulties I had in reading about the issues addressed in the novel. The book as a whole delves into the racism that was so present in the south, particularly in Alabama, in the early twentieth century. The story also deals with issues such as rape, something that I had never really understood before. And I certainly did not fully understand the racial context or the horrific events that occurred in this conflict after reading the book the first time.

Sophomore year of high school, I read To Kill A Mockingbird for a second time as a required reading for the class. After having matured almost four years, reading a wider variety of texts, learning more about the history of the United States, and having more life experience in general, I came to a more complete understanding of the content of the novel. During my second read, I was able to connect the language of the text to the content of the story, and vice-versa. In this way, I was able to see so much more of Harper Lee’s intent as a writer, and was that much more appreciative of Lee’s literary talent. For the first time I was able to understand what makes To Kill A Mockingbird a “literary classic” after all. The book is a daring story that reveals the ugly truth of American history through beautiful language, fully developed characters, and an intricate plot, all serving to create an interesting, enjoyable, and most of all, impactful read. It is for the same reasons that the book is a classic that it is banned; therefore it is important that we continue to read such novels.

Sofia:

Banned Books Week: Are we really challenging anything?

As every bibliophile knows, or friend of a bibliophile knows, there’s a week a year when it’s difficult to escape literature, and that is Banned Books Week. While I felt compelled to rant about my absolute favorite books of all time, which are, consequentially (or not) in the top banned list, something else struck me as compelling in this week-long event. This happened while browsing through the books in the American Library Association’s ‘Banned and Challenged Classics’, and snippets of dialogue and images resurfaced the further I went down the list.

I will make a claim, and don’t leave me hanging here, but a good deal of the best books ever written are on that list. And by ‘good’ I mean to say I’m no moralist, and believe as Oscar Wilde that ‘there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written, that is all;’ which leads me to think about how the books taught in High Schools, written about in essays, revered by kids coming of age, and transcending the geographic and temporal boundaries by which humanity is constrained, enclose a sufficient amount of information deemed offensive by people or institutions, that to this day report them as inappropriate to the Office of Intellectual Freedom. This in turn is quite the antithesis because it implies that by limiting freedom one can somehow become free–when freedom in itself is a polarized notion, given that there either is or there isn’t, no freedom is partial otherwise it’s called something else. So why ban them?

During my teenage freedom spree I had a stage of embracing the unknown, very much like Emil Sinclair from Hesse’s Demian, who finds sanity in corruption and fascination with the occult. I thought of myself as grown up and perhaps even literate (at sixteen, mind you) and that the fact that I read what others frowned upon was somehow challenging not only my own beliefs, but the beliefs that I and my peers were brought up with. As exhilarating as it was to think that whichever book I held in my hands had some sort of higher implication, a silent rebellion of sorts, this existential battle was transfigured a week ago in a discussion for my Freshman Writing Seminar, Sending Smoke Signals: Representations and Realities of Native America.

While looking at distinct works from native and non-native authors, as well as understanding them within a historical context, we began to engage in a dialogue that questions their veracity, misinformation and perpetuation of stereotypes. What this has led me to contemplate is the way in which the transition from reception to interpretation, and how not asking questions (or knowing what the ‘right ones’ are) can lead to a state of mind that is as inert or unchallenged as those unexposed to a particular piece of creative endeavor.

Many artistic representations that we have grown up with have conditioned us in terms of social interaction, perception, and idiosyncrasy to the point of not being able to discern how much of what we have been taught is, if at all, true. Art and media in life and literature can be in many ways misleading, corrupted, or misconstrued by perpetuating misconceptions, feeding stereotypes, objectifying minorities and disempowering entire social groups. But when was it established that knowledge is in any way measured or moral? Is it not true that experience leads to knowledge, not only of times past but of present realities, and if so, why resist it?

While on one hand censorship is limiting, knowledge can be as well if no further analysis is pursued. Statements aren’t always facts, and even if they are, they must be contextualized in a broader spectrum in order to fully assimilate their significance. There is no absolute knowledge or all encompassing truth, though we build our own the more we read and learn.

So in the spirit of Banned Books Week, my wish is that we never stop challenging perspectives, read more widely, and realize that the acquisition of knowledge is as active a task as is breathing, and the lack of it would signify not only the cessation of a cycle, but the conclusion of an enterprise. A book extends beyond its last written page, and it’s up to us to discover where it leads.

Taylor:

Author Oscar Wilde once said that, “[t]he books that the world calls immoral are the books that show the world its own shame.” I wholeheartedly agree with this statement. And it is a shame that books like Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, for example, have ever been banned. A resident of Cherry Hill, New Jersey “feared the book would upset black children reading it,” which, as a young black woman myself, I suppose is a nice gesture. However, if we banned every publication that would potentially upset black children, let’s just say we’d waste a lot less paper. Lee’s book, though, would still be on shelves, along with my favorite banned book, Jodi Picoult’s My Sister’s Keeper.

If you haven’t read or heard about it, My Sister’s Keeper tells the story of 13-year-old Anna who files for medical emancipation from her parents when she finds out she has to donate one of her kidneys to her sister Kate. The story is further complicated by the fact that Anna was conceived for the sole purpose of donating various organs and cells to Kate, who’s dying from leukemia. Additionally, the relationship between Anna’s lawyer and her court-appointed guardian proves to be a rather interesting subplot, as does the delinquent behavior of Anna and Kate’s neglected brother Jesse.

Despite how much I love this book, I almost understand why it’s been banned in the past. The reason listed on the American Library Association’s website is that it’s “too racy for middle school students,” which I think is ridiculous. I read this book for the first time when I was in middle school and, if anything, all the medical and legal jargon was difficult to wrap my head around. It took forever to finish because I had to keep stopping and looking words up. That’s no reason to ban a book, though. While I disagree with the rationale on the ALA’s website, I see and do understand a different reason why My Sister’s Keeper has been banned: it probably scares some parents senseless to see a 13-year-old have so much agency over her own life. Think about it: this little girl is routinely picked apart to help hold her sister together. Her parents tell her to do it. It saves her sister’s life. Plus, it’s literally what she was born to do. The idea of Anna refusing never even crossed her parents’ minds, though her father did understand her choice. The way she stood up for herself was incredibly brave and beyond empowering to read…as a fellow student. If I were a parent, though, my mind would be flooded with questions. What if my child starts to think for him/herself? What if I ask my child to do something and s/he refuses, not out of defiance, but out of a legitimate sense of self-preservation? That just won’t do. I’ll just ban it. Kids never read banned books, right?

Happy Banned Books Week, everyone!