Ten years ago Richard Florida, a regional planning professor then known mostly for comparative studies of industrial management, published The Rise of the Creative Class. His dual thesis — that “creative” sectors were at the forefront of developed-world economies, and that their cauldrons of innovation, economic relations, and human labor were organized by urban form — was galvanizing for a time when urban boosters and economic analysts had only begun to abandon the “smokestack chasing” strategies of the industrial economy in search of lessons from the new economy. In the ten years since, critiques of Florida’s analysis, his booming urban consulting business, and many cities and regions’ uncritical and expensive embrace of his creative-class paradigm have been legion. But no critique has entirely refuted the underlying empirical dynamics that Florida certainly brought to wide notice, but that scholars had been simultaneously observing:

- Technology, design, advanced business and consumer services, professions, academia and cultural production sectors — i.e., the so-called creative industries — are, at their highest value-adding levels, led by the labor-market demands of elite workers, not the traditional organizational dictates of corporations. Perhaps the recording industry notwithstanding, “big business” in these sectors hasn’t exactly gone extinct over 15-20 years of being called “dinosaurs” and “elephants”; in important ways, corporations in these sectors have subsume their labor-control interests to the interests of these elite workers. This move was, after all, an important source of short-term, “flexible,” advantage in the new economy.

- Elite workers vary in the goals they pursue in labor markets, but they characteristically pursue assorted modes of labor autonomy in the workplace and throughout the broader sphere of labor reproduction. The latter points to the domains of private life, the schedules and balance of work and life, socializing and socialization outside the workplace, and — maybe most visibly, but not cut from a cloth wholly different than the other domains — the geographic location of the workplace.

- In the flexible organization of (let’s just use Florida’s shortand at this point) creative sectors, workers’ life course and cohorts constitute an important terrain upon which labor control is negotiated. When managers need workers to commit to burn-out “start-up” hours on the job, then single, child-free, 20- and 30-somethings start to characterize the workforce. When workers’ immersion in the latest collaborative practices, academic wisdoms, consumer styles etc. are sources of economic advantage in talent-driven industries, then the workplace takes on trappings of the college dorm. And when business involves the churn of start-up firms, the project-based hire of talent and independent contractors, and the regular vascillation between periods of intense work/high pay and no work at all, then the lives of elite workers start to resemble episodes of serial workplace monogamy punctuated by bouts of “sabbaticals” and the reordering of personal “values” and wants, with each stage textured by settings and milieus corresponding to workers’ lifestage and peer (sub)cultures.

Florida’s explanation in

The Rise of the Creative Class of “creative” (elite) workers’ labor-market demands is lacking, I’ve always thought, because he understands these workplace/workstyle features as intrinsic to workers’ values and modus operandi. In fact, since the late 1970s the creative economy is enabled and constrained by the broader dictates of “flexible” management and the market organization of everything — the relations of employment and workplace, the spheres of social reproduction, and policy thrusts in social welfare and economic development — that we call

neoliberalism. But, fine: thanks to Richard Florida, the lifestyles, workstyles, and place-based amenities that creative workers pursue have become germane topics where popular/policy interest in urban economic development are concerned. This shift in the discussion is appropriate, given the empirical research, if not the last word on the matter.An issue that’s obviously pressing when these economic dynamics are in play is the hierarchical racial and class ordering of the creative economy. Surprisingly, this issue hasn’t been taken up in a sustained, multidisciplinary fashion. Why not? To name four examples of critical scholarship on these new economy regimes,

Richard Sennett,

Richard Lloyd,

Andrew Ross and I have been focused on the external forces and structural contradictions embodied by creative workers and their workplaces. It’s one thing to recognize that capital externalizes costs upon groups and communities not advantageously tapped into the highly educated, highly mobile, and largely white workforce, but it’s another to devote attention to those groups and communities. And while this scholarship has paid considerable attention to the consumerist lifestyles and complex gentrifying gaze with which creative workers transform the cities and neighborhoods they inhabit (Lloyd’s idea that neobohemians make residential decisions and consume urban amenities through the prism of “as-if tourism” is especially clever), it hasn’t yet satisfactorily examined the costs and contradictions of the creative economy from the spatial/global bottom up, as it were.These shortcomings in the critical urban scholarship on the creative economy underscore the much-needed contribution of

Culture Works: Space, Value, and Mobility across the Neoliberal Americas (NYU Press, 2012), the latest book from anthropologist Arlene Dávila. In it, Dávila advances a powerful critique of the creative-class paradigm, particularly its proposals for culture-based urban economic development and its ideas about creative workers’ migration (the latter an increasingly explicit subject of Florida’s last three books). In significant contrast to many of Florida’s critics, Dávila doesn’t arrive at her critique from a traditional urban studies approach. From the field of Latino/a and Latin American studies, she explores the racialization of the creative economy not just in terms of material inequalities of socioeconomics and geographic mobility (these being the usual focus of sociologists like myself), but also the cultural politics of representations that legitimate and contest these inequalities. As an anthropologist, she brings ethnographic insights into the ethnic enclaves and developing-world populations that are impacted by — and, in turn, challenge — creative-economy restructuring and the state policies that promote it. Dávila’s institutional analysis is keen, particularly regarding the state and nonprofit agencies that promote arts, culture and tourism. Around the middle of the book, chapters on the behind-the-scene politics of museum formation and arts funding, among other things, reveal her further deftness in radical cultural advocacy and art criticism.Dávila’s ultimate target is neoliberalism itself — the actually existing neoliberalism that encompasses the trends in economic restructuring and urban policy described above, as well as other developments on the geopolitical scene. Neoliberalism further entails the highly contested opening of developing world economies to capital: not just the establishment of export processing zones and global commodity chains familiar to observers of the international division of labor, but to flows of real estate investment and tourists from the global north. The state hardly shrinks away under neoliberalism; while rolling back public welfare services, it actively promotes and enforces neoliberal policies by deploying regulatory and policing/military powers on behalf of private interests. Legal codes proliferate to regulate contract activity and public-private ventures in the sphere of commerce. Alongside parallel developments in the nonprofit sphere (particularly to organize funding allocation and grant competitions), these shifts in state and legal activities valorize firms, cities and individuals as competitive entrepreneurs in the market, and accordingly encourage evaluations of social goods and activities in terms of their value to economic well-being. Additionally, with the safety net pulled back and rights of citizenship narrowed around capital’s needs, the informal sector blossoms in a variety of ways — one of neoliberalism’s unsurprising paradoxes.’Culture’ in all its manifestations is especially affected by neoliberalism in two key ways, as Dávila argues. First, cultural producers are evaluated, celebrated or denied institional support in terms of the economic benefits they generate; this is a crucial implication of the creative-class paradigm, if not Richard Florida’s original intent. Second, as evoked by the title Culture Works, cultures of expressivity, geography, community and identity are (in Dávila’s words) reduced and instrumentalized into economic policies. This is the gist of contemporary place branding and state promotion of tourism most notably, but it further involves the institutional regulation and hierarchical ordering of cultural producers themselves into primary and secondary tiers. To put a New York city face to this dynamic, Davila invites us to imagine a “highly educated, white, liberal, Brooklynite independent writer” from the economically ascendant, institutionally sanctioned ‘creative economy’ alongside the

barrio creatives of East Harlem, the city’s venerable Puerto Rican enclave:

In today’s economy, street writers, bomba y plena dancers, and tamale makers are not regularly considered cultural creatives…. When [these] local cultural creatives are recognized, it is primarily for providing background, color, and vibe, rather than as agents who in and of themselves are worthy of investments and policy initiatives…. The question I ask is, how can [New York City] be so widely considered “the global arts capital” when the majority of its residents remain at the margins of its creative economy? And how would the city’s economy be enriched or transformed if we accounted for the hidden contributions of its cultural workers of color? (pp. 73-5).

Dávila organizes the book into three sections corresponding to three research sites that comprise a suggestive tour of cultural productions and political stances by Latino/as and Latin Americans across the Americas. The first is Puerto Rico, the de facto colony of the United States where consumption-based investment (in the form of shopping malls and public-private artisanal fairs) has recently increased under the pro-business/pro-statehood policies of Governor Luis Fortuño. The second is New York City, where Latino/a cultural advocates have challenged the institutional funding and curatorial criteria that customarily disenfranchise Latino/a artists and cultural producers. (Their battle extends geographically to Washington D.C. for one chapter documenting the struggle to establish a National Museum of the American Latino as part of the federally funded Smithsonian Museums.) The third is Buenos Aires, where tango music and the urban scene have drawn growing numbers of visitors and migrants under the anti-neoliberal administration of President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.The section on Puerto Rico examines spaces of cultural consumption and production. A chapter on shopping malls extends the “point of purchase” analysis of

Sharon Zukin and other consumption scholars, by examining into how shoppers recognize and contest the national stereotype that (as one informant) “shopping is our national pasttime,” with the highest density of shopping malls across Latin America. Modestly interesting, this chapter sets up a far more engaging chapter on the folk art/craft fairs sponsored by shopping malls and other private interests looking to generate consumer traffic with artisanal events. Traditionally a field informed by strong cultural nationalist sentiments and dominated by older male artists, folk art has exploded as an informal income-generating strategy for Puerto Rico’s poor and (more recently) middle classes who have lost earnings and jobs under neoliberal economics.In this chapter, Dávila articulates two themes that recur throughout

Culture Works. First, the incorporation of cultural production under neoliberal enterprises and their emphasis on extrinsic criteria of economic benefit invariably triggers

authenticating discourses that are contradictory and interpreted differently among different stakeholders. Second, at least where cultural producers are concerned, neoliberalism and the claims to authenticity that emerge to challenge it give rise to a curious phenomenon of middle-class informality. It takes social capital to get choice spots in these fairs, and cultural capital to explain to sponsors and regulators how innovative craftwork falls under the umbrella of nationalist artisanal tradition. Without these forms of advantage, poor and unlucky artisans have to resort to crashing fairs and setting up in unsanctioned events that police regularly shut down; they find themselves in disrespected fields like craft jewelry and unable to successfully explain how their work satisfies the highly regulated standards of national folk art.Hierarchical conflicts over artistic authenticity and economic value resurface in the section on New York, where Latino/a artists and cultural advocates find themselves on the institutional defensive in museums and galleries. The still-ongoing initiative to establish a National Museum of the American Latino finds itself running headlong into the unfortunately familiar culture-war demand that it “benefit ‘all the cultures that make up the American identity, and [present itself] foremost about reinforcing U.S. national identity, rather than only one of its components” (pg. 99). In New York City, cultural advocates for communities of color band together as the Cultural Equity Group (in which Dávila has participated extensively) to challenge two expressions of institutional bias in the city’s art fundings. First, in a city of over 1400 recognized arts and culture groups, 34 institutions receive 75-80 percent of the city’s art budgets. These recipients include famous institutions that are no doubt legitimately funded, at least to some degree, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the American Museum of Natural History. But why aren’t the New York Historical Society, the Whitney Museum of American Art, much less the great number of institutions representing the arts and cultures of NYC’s ethnic communities?The second form of institutional bias comes from the aesthetic criteria adopted by curators and arts funders alike. While it’s romantic to believe that “art for art’s sake” is the best principle by which the artists can challenge neoliberalism’s insistence on economic value, this belief is premised upon “the dominant Western-based universalist notion that art is most valuable the more global, universalist, and disconnected from particular communities it is posed to be” (pg. 113). Organizations in the Cultural Equity Group are systematically disadvantaged by this belief. Generally originating from the city’s civil rights and ethnic nationalist struggles of the 1960s and 70s, these groups serve communities of color through multidisciplinary programming that can include neighborhood development and residential empowerment; to that end, they’re sometimes receptive to public-private solutions that are anathema to the romantic “art for art’s sake” perspective. As Bill Aguado of the Bronx Council of the Arts explains, “They see us as a social service organization, but not as arts groups or as valuable assets…. It’s all a colonial situation” (pg. 87).In fact, community engagement and collaboration with so-called social service missions can be enriching experiences for artists, as Dávila learns from Miguel Luciano in a chapter dedicated to this young artist whose work is celebrated for its pop-culture savvy and conceptual ruminations on Puerto Rican identity:

One of my challenges in accessing [traditional galleries and] commercial spaces is that these have not been the most interesting spaces for my work, because they are interested in the bottom line and in selling to their base. I’m interested in having these conversations about culture, history, identity, and empowerment, and this type of work works best with institutions where I can work with communities and where a conversation can be built around the work and where the concern is not with the market but with the experience of the work (pp. 123-4).

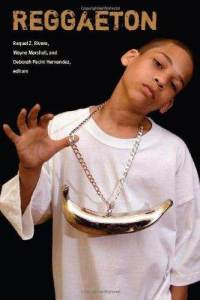

Platano Pride, a 2006 sculpture by Miguel Luciano

as featured on the cover of Reggaeton by Raquel Z. Rivera et al (eds.)

Overall, Dávila is skeptical of the vision that creative-city boosters would have us entertain of creatives and visitors actively “engaging” some generic, ethnically unspecified urban arts scene:

Connection to place represents another significant impediment to the evaluation of barrio cultural creatives. Our contemporary creative economy values movement and mobility, and it is “fickle” cultural initiatives that can pack up and leave that are most valued and that are said to require incentives and to demand romancing: the chain restaurant, the Starbucks, the museum from downtown seeking a cheaper location in a gentrifying neighborhood. In contrast, cultural institutions that are anchored in place, or whose activities revolve around their identity, are easily taken for granted. Most problematic, barrio creative work is devalued because it is regarded as instinctual to ethnic communities and lacking in any training and expertise. You are Puerto Rican; you dance bomba y plena. You are Mexican; you cook tamales. It is what you do; it is in your DNA. You are moved to “protect your culture” for ethnic pride or, in the eyes of many people, for ethnic chauvinism. If no higher degree is involved, if you do not come packaged with the appropriate credentials, then there is no creative work to talk about, despite the hours of training and the sacrificed income that characterizes most cultural work (pp. 81-2).

Mobility moves to the forefront of Dávila’s section on Buenos Aires, which to my thinking is the high point of Culture Works. The two chapters here make the most explicit and valuable contributions to urban studies and cultural geography, and Dávila’s ethnography is at its liveliest, not least because she’s a participant in the “tango tourism” that provides one chapter’s subject. This phenomenon refers to the marked boost in tourism to Buenos Aires since 2002, when Argentina ended its economic crisis by devaluing the peso devaluation. At the center of this tourism, mostly from America and Europe, is the consumption of tango music, in the form of experiences (dancing in tango venues, watching others dancing at themed restaurants, taking lessons, navigating “tango maps” of the city) and goods (CDs, “tango shoes,” etc.). Tango tourists correctly recognize that this globally popular dance and music came from Argentina, but few grasp how local Porteños (residents of the port city of Buenos Aires) regard tango with greater ambivalence. Most importantly, the generation that lived to see decades of military repression in Argentina end associate tango with this era:

Decades of military repression, alongside a postcolonial-fueled resistance to the acceptance and validation of tango, took a toll on how Porteños learned and related to the dance, to the point that few dancers, except newer generations or older dancers, have memories of learning to dance within the family or in intimate social encounters. In my interviews, older dancers recalled that after the Revoluión Libertadora in 1955, tango dancers would be followed from milongas [tango dance venues], questioned, and harassed by the police and that subsequent military governments promoted rock music and global rhythms, which were considered less politically volatile. Because of this legacy, learning to dance tango has become a matter of schooling, a time-consuming and costly venture more accessible to middle classes than to the popular sectors that historically originated it. In sum, the tango-Buenos Aires connection is not generalizable to the entire city or to all sectors of society. As one musician explained, “There’s no tango in the villas miserias[slums], there’s no tango in the provincias [provinces].” There you are more likely to hear cumbia or other more popular rhythms” (pg. 139).

Tango in Argentina is thus consumed primarily in delimited spheres — highly sanitized tourist bubbles in the day, milongas at night where foreigners outnumber Porteños as much as four to one. This is of course a fertile environment for authenticating discourses regarding tango. Dávila describes how controversy abounds over flashy kicks and exaggerated moves, and how umbrage is taken over clumsy dancers or foreign women unable to wait for the initiating “look” from a male Porteño. Controversially, in 2011 one tournament organized by city government was targeted to “Argentine natives” and required one partner to be an official resident of Buenos Aires. Yet Porteños’ participation in tango is complicated by class and race. Tango’s economic benefit to Porteños is enjoyed mainly by middle-class participants, those most likely to have the training and English-language proficiency that result in renumerable opportunites, from “taxi dancing” (male dancers for hire) to careers in performing or teaching overseas. Moreover, the high cost of admission to milongas as well as the broader impacts of tourism-fueled gentrification means “locals can hardly afford to go dancing on a nightly base, as is commonly done by tourists.”In fact, many Porteños look favorably upon foreign tango enthusiasts, distinguishing mere “tourists” from those who appreciate the dance in good faith, and even recognize them as “

gente como uno” (people like us). As Porteña dancer Susana Miller explains, “

No hay extranjeros en el tango, si entendés el tango como producto porteño” (There are no foreigners in tango, if you understand tango as a Porteño product; pg. 158). This moral identity, obviously a source of collective pride, is infused with middle-class anxieties over Buenos Aires’ stature in the world at large in the era of the devalued peso. Few Porteños are able to visit the global north as easily as tango tourists do their city. However, the popularity of their dance and their city with Americans and Europeans —

especially Europeans, since Argentina has long been regarded as the most European of Latin American cities, a distinction that connotes a troubled history of Peronism and racial classifications vis-a-vis indigenous people of color — offers a sense of symbolic citizenship that compensates for this economically downgraded status.The book complements this supply-side view of Buenos Aires’ allure with a chapter on the demand-size view of Buenos Aires’ burgeoning expatriate community. Many expats cite tango as the initial attraction (for instance, read “lifestyle designer”/self-help dude

Tim Farriss’ perspective on Buenos Aires), but even the choreographically challenged find much to admire in the city’s cosmopolitanism, urban amenities, easy-going way of life, and advantageous cost of living. The city certainly makes it easy for expats to stake a claim in Buenos Aires, rarely checking white foreigners’ documentation and ushering in urban gentrification by opening neighborhoods up to residential/commercial property developments in residences and commerce suited to expat tastes.Dávila’s key insight is that expats’ view of Buenos Aires living is spatially relational, predicated upon “the ‘wages of empire’ afforded by their nationalities, in ways that soften the economic uncertainty, insecurity, and downgrading that increasingly characterizes workers in creative sectors in the United States and Europe” (pg. 166). She elaborates:

This quest for a more balanced life was repeatedly mentioned by expats I spoke to, who openly shunned the stress and tediousness that they felt was characteristic of their respective career paths back home. Drawing on familiar dichotomies of rationality versus emotion, work versus enjoyment, and technology versus arts and beauty that have historically circulated as part of nationalist/imperial ideologies to distinguish the United States from Latin American countries, they tended to see Argentinean culture as an oasis of familiarity, social life, enjoyment, and liesure that many believe to be characteristic of Argentinean culture and the unique cultural disposition of Argentineans, rather than the product of the political and economic conditions that facilitate expats’ ability to achieve a greater degree of leisured living (pg. 174).

Although Dávila doesn’t inject her analysis of expats’ mobility with a great deal of theory from economic geography, this chapter provides illuminating ethnographic detail on the economically structured geographies through which people migrate from industry cores in the north to discretionary destinations in the peripheries. These are “creative” geographies not because the creative workers necessarily appreciate urban and cultural amenities more than other people (despite what Richard Florida might insist), but because their economic identities and “flexible” employment give them greater freedoms to prioritize lifestyle and pursue those priorties in places of their choosing. (In my writings, I’ve called these people

quality-of-life migrants, and places like Buenos Aires

quality-of-life districts.)In these geographies, success in labor markets back home inform the status hierarchies that expats enter into in Buenos Aires. At the top, the group Dávila calls “cyber workers” still draw high incomes from the north and thus have the greatest resources to enjoy the city at its fullest, if only for finite periods of sabbatical. Retirees also experience the city this way, although perhaps at lower income levels. Then there are various categories of labor-market dropouts who couldn’t afford this quality of life back home. Many of these become entrepreneurs in Buenos Aires, filling a peculiarly non-local niche: bed and breakfasts, taco restaurants, bagel and cupcake shops, and so on. “A few expats have even become successful brokers of Argentinean culture abroad,” Dávila notes, describing the case of electro-cumbia DJ Grant Dull, who internationalized a local music that underground Porteño DJs lacked the connections, savvy and influence to market abroad.

If the cultural gaze with which expats often view Buenos Aires is often explicitly colonial — one expat describes the city as an ideal “halfway house” between the global north and Latin America (pg. 177) — it nonetheless finds some sympathetic reception among Porteños who have internalized the colonial assessment that their city is less “modern” than the European centers it was modelled upon. In this way, a moral reciprocity is established between expats and Porteños, neither quite seeing the other in their individuality so long as they symbolically soothe each others’ cultural anxieties.I confess to not being very familiar with Arlene Dávila’s scholarship, so among other things I don’t know if she would call herself an urban anthropologist. But the Argentina section highlights how

Culture Works is an important work of urban anthropology, insofar as the latter revolves around the study of people’s movements to cities. Customarily this is the move of indigenous or rural people to cities, still the most important manifestation of ‘urbanization’ in the developing world, but Dávila has pulled off a cool trick in redirecting the urban anthropological question toward a developed-world group celebrated (by Richard Florida, at least) for their peripatetic mobility and consumption of place.If Dávila insightfully strips the presumption of geographic immobility (which is traditionally an outcome of socioeconomic security) from the privileged groups in urban hierarchies (in this case, “creative classes”), I found myself once or twice nagged by how she problematically projects the presumption onto barrio creatives. On the whole, she succeeds her in aim “to expose that creative industries generate particular mobilities, that they favor certain type of mobile bodies while circumscribing the social and physical mobility of others” (pg. 16). And at least where mobility into elite institutional settings for art training and grant funding are concerned, she elaborates and further illustrates the concern that art historian Yasmin Ramirez raises in regards to New York art funding: “It’s not enough to say black and Latino organizations. You have to focus on the communities these organizations serve, and where they’re located, and address the class dimension at the heart of why some institutions serving blacks and Latinos languish and others are able to get monies and tap resources.”But then there’s the case of Miguel Luciano, the Puerto Rican artist who is the subject of a whole chapter in

Culture Works. Luciano was born in San Juan, received his MFA at the University of Florida, and then moved to New York because, Dávila reports, “he was attracted to what he described as the city’s symbolic importance for the Puerto Rican community” (pg. 113). A crucial event in his career was his first mainstream gallery show, curated by Juan Sanchez at the Chelsea-based CUE ART Foundation.

Luciano’s selection for a solo show by the revered Nuyorican artist Sanchez was especially meaningful to Luciano and was evocative of his longstanding identification with the Nuyorican artistic community. Juan Sanches is not only one of the few Nuyorican artists who has received nationwide legitimacy from mainstream galleries and collectors; he is also an artist who has never been shy to explore topics related to Puerto Ricans’ identity and experiences with poverty, colonialism, marginalization, and empowerment both on the island and in the Diaspora. These are concerns that Luciano shares with Sanchez and that induce his pride in having his work identified with a Nuyorican artistic tradition, even though, in his own words, he is a “transplant” who did not experience what he described as a “typical” Nuyorican trajectory, having moved to New York City from Florida. The key identification is neither geographical nor historical; a “Nuyorican” tradition is thus conceived as the extension of the politicized and community interventions of Taller Boricua and the community of Nuyorican artists who broke artistic barriers in the 1980s alongside the Nuyorican movement to formulate the work that was in intimate conversation with the empowerment of the Puerto Rican community both in the States and on the island (pg. 121).

The issue I find odd here is an inconsistency (or, worse, a double standard) in what Dávila regards as legitimate mobility for the creative class. His artistic interests notwithstanding, Luciano surely counts as the creative class, not the barrio creatives — if an MFA and critical acclaim doesn’t give you that status, what does? His community membership among Nuyoricans is symbolic, not ‘real’ in terms of residential origins. How then does his mobility and institutional status not put him on the wrong side of the “class dimension” (in Hernandez’s words) that divides artists and artistic institutions of color? I don’t think an answer necessarily involves revisiting or reworking identity politics, so much as an acknowledgement that mobility is a more complex phenomenon that Dávila describes. It’s among this book’s many achievements that Culture Works introduces such questions into the on-going critique of the creative economy and its simplistic celebration.

View on the Musical Urbanism site.