Given a long and ongoing history of racism, characterized by the enslavement, repression, and exploitation of black bodies, what prompts the world’s Black communities to join the American public as immigrants?

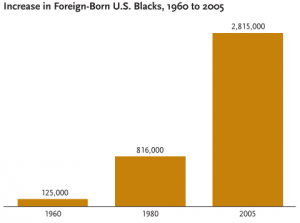

Because of the color of their skin and shared ethnic roots, international Black peoples may not be unaffected by the racial caste system which U.S. native-born blacks have endured since this country’s founding. Despite this, about eight percent of the U.S. foreign-born population is comprised of Black immigrants (Faris 2012). These immigrants were even responsible for at least one-fifth of US-born black population growth between 2001 and 2006! The foreign-born Black population has been on the rise since the latter half of the 20th century, proceeding from a 150 year period of sparse immigration (Kent 2007:3,4). As America – the ‘Nation of Immigrants’ – approaches an increasingly cosmopolitan population, how will the future of race relations and international diplomacy shape the trajectories of our Black immigrant communities?

A clarification of terms: Who, what, and where is Black?

‘Black’ is used loosely in this discussion so as to represent both the racial and ethnic categories which Black individuals embody. When populations are referred to as Black in an ethnic context, it is to say that they have common ancestry and cultural elements rooted in African diasporic communities. These are the cultural groups which originated on continental Africa and were dispersed throughout the Americas and the Caribbean during the Atlantic slave trade. Black ethnic communities will differ from one another; there is no single culture that represents the Black ethnicity. In a racial context, Black will be discussed as the American classification of individuals who might have a common skin-tone, ethnic background, or social/cultural affiliations often associated with those who might be called ‘African American,’ or those with longer US-born lineage dating back to American slavery. Diamond Sharp, editorial fellow at The Root, sheds light on the Black racial/ethnic distinction,

“I think what’s at the heart of much of the discord is that, because of racism in the United States, “black” people get lumped together. Our respective histories and cultures are not recognized or valued. We may all share a skin tone, but our cultures are not the same. People have the right and the need to identify themselves with their respective cultures.” (2014)

In respect of the multitude of cultural realities that blackness encompasses, it may be useful to read into the context in which a community is labeled or self-identified as Black throughout this article.

Black Immigration: Demographics and Origins

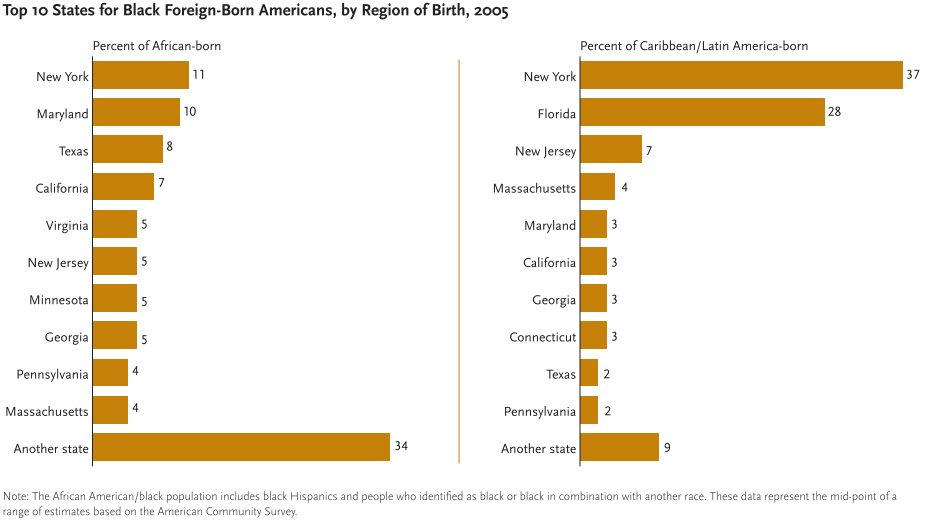

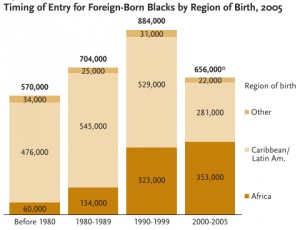

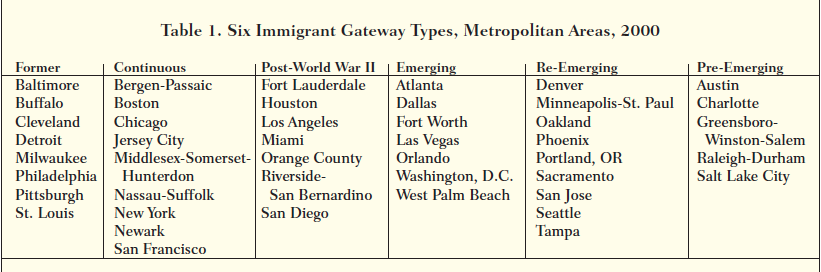

About two thirds of America’s 2.8 million foreign-born Black population in 2005 came from the Caribbean and Latin American countries while one third were born in Africa. Black foreign-born Caribbean immigrants are largely from Jamaica, Haiti, Guyana, and Trinidad and Tobago. From Spanish-speaking countries, most Black immigrants are from the Dominican Republic, Mexico, Panama, and Cuba. The majority of black African immigrants are from ten countries: Nigeria, Ethiopia, Ghana, Liberia, Somalia, Kenya, Sudan, Sierra Leone, Cameroon, Eritrea, and Guinea. Together, these ten countries account for 70 percent of black immigrants of African origin (Kent 2007:4-7). Black immigrants, like many others, settle throughout America’s metropolitan cities, as seen in the figure below:

While all Black immigrants tend to settle in America’s metropolitan centers, Black African immigrants are more largely dispersed throughout the country. A look at the contexts of Black African and Caribbean/Latin American immigrants sheds light on the factors that lead these groups to the US.

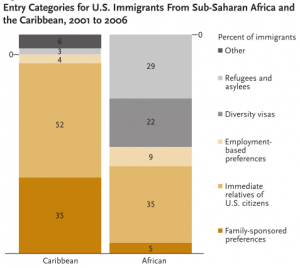

Black Caribbeans and Latin Americans

Observable by their high numbers, Caribbean/Latin American immigration is facilitated by their close proximity to the US. Over 80 percent of recent immigrants form these regions gained entry to the country through family members who already lived in the US. As seen above, a large majority of these families were already situated in metropolitan areas (Kent 2007:5). These immigrants were largely driven from their home countries due to a lack of economic opportunity. Thus, facilitated by their strong English skills, many Caribbean immigrants will enter the country as business travelers, or will join a temporary work or study program (5, 11).

Black Africans

With the African continent more distant and voluntary migration being minimal after the slave trade, most of the growth in the black African population has occurred within the last two decades. In fact, Black Africans are now some of the fastest growing immigrant populations in the US.(Capps 2012:2). The 1980’s is (crudely) considered by many to be Africa’s “lost decade,” when many African countries experienced political instability, economic deterioration, and extreme poverty. At the same time, America was becoming a hub for international study with the introduction of diversity visas, which sought to increase the influx immigrants from underrepresented countries (Kent 2007:4,5). The factors drove most recent Black Africans to enter the country as refugees or through diversity visas (See Kent 2007, Figure 3 above).

The Bigger Picture of Black Immigration

Education

The Center for American Progress states that Black immigrants are among the most educated immigrant populations in the US! This might reflect the fact highly educated Black Africans and Caribbeans are selected for immigration. Grace Kao in Education and Immigration states that immigrant populations may differ from the general population of their home countries because certain individual characteristics provide better opportunity for entry to the US (2013:76,77). The most educated and highly skilled African and Caribbean immigrants will be more likely to receive diversity visas, or be able to afford the cost of travel to the United States. In fact, recipients of diversity visas require at least a high school degree or two years of employment or training (Capps 2012:12).

Transnational Identities

Black immigrants often retain strong cultural ties to their home countries. Black Caribbean immigrants speak more English at home than African immigrants, but they are likely to speak an English dialect such as Jamaican or French Creole. Black Africans are more likely to speak an African language in the home (Kent 2007:11). Some Black immigrants may live together in ethnic enclaves. These are communities of people with common ethnic roots, where individuals can retain their cultural values and network with one another through businesses and other institutions (Rumbaut and Portes 2001:loc.1414). Some of the economic success that Caribbean immigrants are often associated with reflects the mobility that Caribbean enclaves have enabled. Caribbean immigrants, being so close to the US, maintain strong connections to family and friends abroad. African immigrants are likely to continue to engage in their home country’s politics. Both groups may send money home to their families (Kent 2007:15). These connections help Black immigrants craft their dual identity as Americans and peoples of the international Black community.

Facing Discrimination

Persisting racial inequality in the United States leads some to postulate that Black immigrants may come to join the American underclass with US-born African Americans. The underclass is seen as class of peoples whose socioeconomic or racial background leads them to downward socioeconomic mobility, which their potential for growth capped by structural inequality (Alba and Nee 2003:loc.3562). While the validity of an American “underclass” is debatable, the concept reminds us that racial perceptions can severely limit opportunity for non-whites in the US.

The Center for American Progress claims that despite the Black Africans’ high educational attainment, they earn lower wages than immigrants with similar credentials. While Black Caribbean immigrants are valued for their strong English fluency, African immigrants often are devalued for their poor English capabilities and strong accents (Faris 2012). Both negative perceptions of Africans and American blackness can contribute to the psychological and socioeconomic strife that Black immigrants will face as they navigate American society.

The Future of Black immigration

How will current events shape the future of Black immigration?

Following the recent American acquisition of Ebola, there has been a surge of anti-African xenophobia in the media. There are reports of African students being bullied barred from attending classes stemming from these fears. Simultaneously, there is an increasing stigma concerning travel to and from Africa, especially in areas with current Ebola victims. How will anti-African xenophobia shape US-African relation outside and within borders?

The rising Black Lives Matter movement, following the shooting of unarmed black teen Michael Brown by white officer Darren Wilson, is creating ripples of dialogue about race relations in America. Black Americans, both US and foreign-born, are joining the masses of individuals who are working to resist structural racism and reaffirm blackness in this country. Will the discourse of Black Lives Matter extend beyond American borders and mobilize Black communities across the globe? How will this discourse shape future tras-national/pan-African identities?

These are some of the questions that we, as Americans, will have to ask ourselves as Black immigration and blackness continue to enter the public eye and the public psyche.

References

Alba, Richard and Victor Nee. 2003. Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and contemporary immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Capps, Randy. 2012. Diverse Streams: African Migration to the United States. Migration Policy Institute (http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/CBI-african-migration-united-states).

Faris, Helina. Center for American Progress. 2012. “5 Fast Facts About Black Immigrants in the United States.” Retrieved November 10, 2014 (https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/immigration/news/2012/12/20/48571/5-fast-facts-about-black-immigrants-in-the-united-states/).

Kao, Melissa. 2013. Education and Immigration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kent, Mary Mederios. 2002. Immigration and America’s Black Population. Population Reference Bureau. Vol. 62, No.4. Washington, DC. Retrieved November 10, 2014 (http://www.prb.org/pdf07/62.4immigration.pdf).

Rumbaut, Ruben and Alejandro Portes. 2001. Ethnicities: Children of immigrants in America. New York: University of California Press.