Background Information on contemporary education and English Language Learners

From 2007-2008, there were 5.3 million English Language Learners (ELL) in the U.S. K-12 public school system, which constituted 10.6 percent of the total student population (Calderón, Slavin, and Sanchez 2011:103). Nonetheless, according to the National Center for Education Statistics Survey (NCES) of 1997, only 29.5 percent of teachers, including ELL specific instructors, reported having had any type of training on how to instruct ELLs (Hite and Evans 2006:89). Although the percentage of teachers may have increased since the NCES 1997 survey, there are currently no federal level policies for states to follow in structuring efficient ELL instruction (Calderón et al. 2011:104). Notably, ELLs have significantly lower academic performance and educational attainment rates than native white students (Calderón et al. 2011:104). In addition, 80 percent of second generation immigrant children labeled as long-term English learners at the elementary level continue to be categorized as having limited English language ability at the secondary level (Calderón et al. 2011:104). Both of these statistics suggest that teachers lack adequate training for working with this student population.

In order to provide a foundation for diverse stakeholders dedicated to educational equity, this guide is organized around the following core elements of effective ELL instruction at the elementary (K-5) level:

- Promotion of English language fluency

- Facilitation of content area learning

- Appreciation of student identity

Promotion of English Language Fluency

Current state of ELL instruction

Many school districts follow the practice of pulling ELLs out of their mainstream classroom once a day for a period of specialized English language instruction. For the rest of their school day, ELLs are expected to learn within a “mainstream” English monolingual, classroom setting. Unfortunately, this “pullout” approach causes many teachers to view ELL differentiated instruction as outside of their professional domain (Calderón, et al. 2011). Because many elementary ELLs spend the majority of their time within the mainstream classroom setting, it is integral that all teachers understand how to promote English language development. As highlighted in the statistical overview, contemporary approaches towards English language development have been unsuccessful. It is imperative to view English language acquisition, or the path towards fluency, as an ongoing, long-term process. The English language acquisition continuum perspective promotes the implementation of lessons and accommodations that are in accordance with ELLs’ language stages.

Reorienting ELL instruction towards the language acquisition continuum

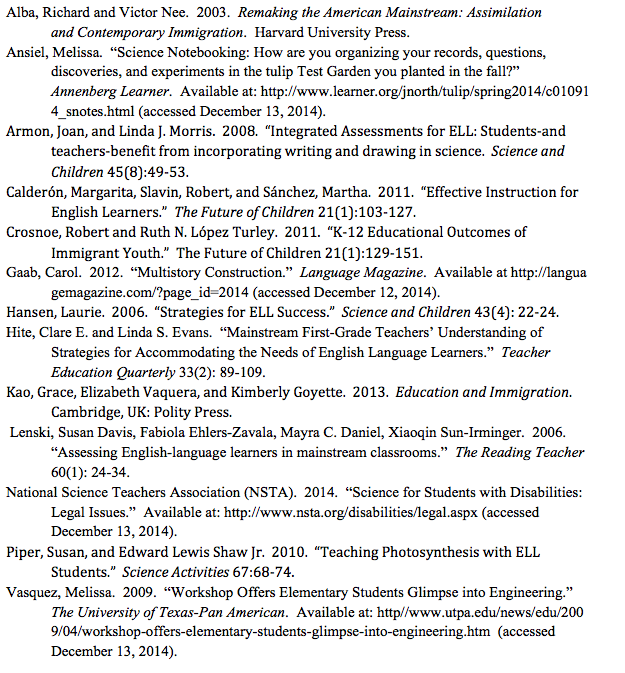

Exemplifying how an elementary study on photosynthesis can be differentiated for the diverse needs of ELLs within a mainstream classroom, Piper and Shaw (2011) focus on five progressive stages of language development. Figure 1 from Piper and Shaw’s (2011) work provides an overview of these five stages. This is a practical application of differentiated photosynthesis lesson activities and communicative devices that ELLs should be given and expected to produce in the course of study depending on their language acquisition stage. For example, Figure 1 shows that an ELL student in the initial “Pre-Production Stage” should work to explain unit information via drawings, symbols, or a few words in the English language. By the “Speech Emergence Stage,” ELLs should be encouraged to express their understanding of content material via short sentences in English.

Figure 1. English Language Learner fluency level in accordance with lesson design and differentiation in an elementary science unit on photosynthesis

Source: Piper and Shaw (2010)

Specific strategies that promote English language development

The English language acquisition continuum is valuable for designing lessons that meet the varying language levels and needs of ELLs. In addition, there are overarching strategies that teachers can use in the ongoing, long-term process of working towards English language fluency.

1. Teacher speech delivery as performance

Figure 2. Illustration of teacher dramatically acting out her oral presentation of a story through gesticulation and the visual aid of puppets

Source: Gaab (2012), Language Magazine

Teachers promote English language acquisition and whole-class engagement by delivering instructions and information in a performance style, dramatized manner. ELL English comprehension skills are supported when teachers utilize gestures, emotion, and facial expressions while speaking clearly and at a relatively slow pace. Moreover, depending on the English development stage of ELLs, teachers should avoid the use of potentially confusing and unnecessary idiomatic phrases. Visual supports, demonstrations, and physical objects are also incredibly helpful for helping ELLs comprehend teacher instruction and gain English language proficiency (Armon and Morris 2008). Teachers should also work to incorporate target, content area vocabulary into their whole-class speeches (Hansen 2006; Piper and Shaw 2010). Please note that the word usage, pace, and extent of dramatization in teacher speech should be structured in accordance with ELLs’ English language developmental stage.

2. Small group work

Figure 3. Example of elementary students participating in small-group inquiry, play-like projects.

Source: Source: Vasquez (2009), The University of Texas-Pan American

Classroom teachers can also promote language acquisition by pairing ELLs and English-only peers together. Hansen (2006) hones in on how inquiry-based activities promote social exchange that mirrors play. Authentic, socially based English language tasks are integral for learning a new language (Hite and Evans 2006). Small group work allows ELLs to practice English in a setting that is less nerve-racking than whole-class discussions (Calderón et al. 2011).

Facilitation of Content Area Learning

Diverse learning backgrounds and needs of ELLs

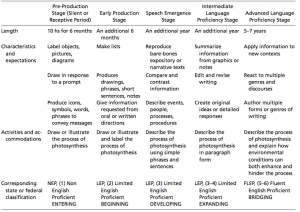

Mainstream classroom elementary teachers are also responsible for providing ELLs with accessible instruction in the content areas, such as math, science, social studies, and the language arts. In order to facilitate content area learning, it is essential that teachers understand that the U.S. ELL population is composed of students with widely varying literacy levels and academic knowledge in their first language (Calderón et al. 2011; Crosnoe and Turley 2011; Lenski et al. 2006). It is also important to consider how both “human capital immigrants” and “traditional labor migrants” (Alba and Nee 2003:230) are involved in contemporary immigration. Human capital immigrants have advanced educational degrees in their country of origin and professional skills, while traditional labor migrants have little to no formal education (Alba and Nee 2003:230). Therefore, the families and communities that ELLs belong to will determine the resources and breadth of knowledge that ELLs bring to their respective classrooms. Seeking to inform educators working with the heterogeneous ELL population, Lenski et al. (2006) underscore how teachers should strive to understand the educational and linguistic backgrounds that students possess. Figure 4 from the work of Lenski et al. (2006) provides a guide based on four possible categories to which an ELL student may belong. For example, Figure 4 shows that some ELLs may enter the classroom with grade-level literacy skills in their first language, while other ELLs may have had limited formal education and lack literacy skills in their first language. Figure 4 also highlights how ELLs may have transnational ties to both the U.S. and their personal, or familial, country of origin. Transnational status may contribute to literacy in Language 1 and Language 2, or in some cases, a lack of literacy in either Language 1 or Language 2.

Figure 4. English Language Learner profiles in consideration of literacy skills, language proficiencies, academic backgrounds.

Source: Lenski et al. (2006)

While Figure 4 offers helpful considerations, it should only be used as a preliminary resource because individual ELLs may have experiences that belong to each of the four learning profiles.

Specific Strategies that promote content area learning

1. Trade Books and Pre-Lesson Conferences

In order to help orient an ELL student to a new unit study, elementary teachers can use simple picture books to introduce content area vocabulary and essential learning themes (Armon and Morris 2008:50). ELLs may benefit from individual-student conferences before a unit study, in which a picture book featuring core content is collectively read and processed through drawings, diagrams, and language appropriate conversations.

2. Language Buddies

An additional strategy is to pair an ELL student with a classmate who is proficient in both English and the ELL’s first language (Hite and Evans 2006:101). Prior to implementing the Language Buddy system, it is important to establish a collaborative classroom community. Teachers should initiate role-play exercises on how students can productively act as mentors and learning partners (Hite and Evans 2006:101).

3. Alternative Assessments

- If ELLs have the literacy skills, they can write explanations of academic content in their first language in order to think deeply about content without a language barrier (Hite and Evans 2006:104). Then, ELLs can communicate key points expressed in their first language composition through pictures, diagrams, words, phrases, or short sentences. Expectations for ELLs’ “translation” of their first language composition should be based upon their current stage in the English language acquisition continuum.

- Informal observations of the ideas ELLs put forth in group-based projects (Armon and Morris 2008).

- Instruction on portraying content area knowledge via pictorial expression (Armon and Morris 2008). And, for student assessments, encourage integration of art and writing.

- Incorporation of journals into unit studies. Journals allow teachers to evaluate the growth of a student in both English language acquisition and content learning over time (Armon and Morris 2008).

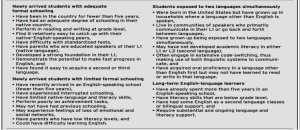

Figure 4. Example of an elementary, student journal that integrates art and writing during a unit study on plant growth.

Source: Ansiel, Annenberg Learner Science Notebooking

Appreciation of Student Identity

Kao, Vaquera, and Goyette (2011) highlight how U.S. school policies and curriculum often “devalue” (135) and “marginalize” (134) the home cultures of many student populations, including immigrant and second-generation children. Language and identity are inextricably linked. Effective instruction for ELLs entails fostering a classroom community in which all students learn about each other’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds. First steps in this process include teaching texts that mirror ELLs’ backgrounds, working towards filling the school library with bilingual books, encouraging ELLs to use their first language as a learning strategy for processing challenging tasks, and crafting projects that capitalize on ELLs existing academic and sociocultural knowledge.

Final Thoughts

Educators who view teaching as a performance, promote student partnerships, integrate multimodal expression, unpack educational policy, and learn about every student as an individual learner and person are not merely working towards effective instruction for ELLs. They are creating a classroom that is inclusive for all types of learners.

Figure 6. Illustration of inclusive education

Source: National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) (2014)

References