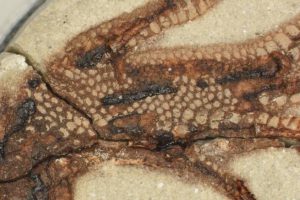

Although tattoos were originally thought to have dated back to around 2,000 B.C to ancient Egyptian times, recent archaeological discoveries have carbon-dated tattoos to be approximately 5,200 years old. Due to such discoveries, the certainty of when tattoos first originated has become rather unclear. In Egyptian times, “the distribution of the tattooed dots and small crosses on the lower spine and right knee and ankle joints correspond to areas of strain-induced degeneration, with the suggestion that they may have been applied to alleviate joint pain and were therefore essentially therapeutic” (Lineberry). Archeological studies have shown that ancient Egyptian tattooing was primarily a practice reserved for women. Tattooing was used “during the very difficult time of pregnancy and birth. This is supported by the pattern of distribution, largely around the abdomen, on top of the thighs and the breasts” (Lineberry). It is believed that older Egyptian women would pass this tradition of tattooing down to the younger counterparts. The symbolic value of the tattoo in ancient Egypt differs drastically from Samoan culture and more parallely resembles ancient Japanese culture.

While tattoos do not date back quite as far in Samoan culture as they do in Egyptian culture, tattooing was a long standing tradition that represented an individual’s rank within the tribe. Tattoos in Samoan culture were most often associated with men; however, “women too endured tattooing, but their patterns were typically smaller” (PBS). The men’s tattoos would, “forever celebrate their endurance and dedication to cultural traditions.”(PBS). Typically, Samoan tattoos started at a man’s mid-torso and extended downwards towards their feet. The process of receiving these tattoos was both an extremely painful and dangerous one. Besides the excessively high risk of infection, the men would experience massive amounts of pain, as the tattoos would typically take up to a year to heal completely. The entire tribe would come together to help support the man who received the tattoo. The tattoos needed to be cleaned daily and the men oftentimes needed help with daily tasks, for even just sitting and walking was rather painful.

While different cultures throughout the world have used tattooing as a way to symbolize their beliefs, it is important to note that although these cultures have tattooing in common, the symbolism behind the practice of tattooing differs from culture to culture. This does that mean that there are no similarities in tattooing practices across cultures. For example, Japan and Egypt both used some tattoos as protective symbols, while Samoa and Japan used certain tattoos to denote an individual’s rank (Kearns). Japan’s tattoo practice incorporates elements of both the Samoan and the Egyptian cultures, but still maintains its own uniqueness (Kearns).

Above is a picture of a traditional Samoan tattoo. One that begins mid-torso and continues downward.

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/new_tattoo_631.jpg)

Above is a corpse that has been mummified and the tattoos that are showing have been preserved over thousands of years.

Reference List

Kearns, Angel. “Inked and Exiled: A History of Tattooing in Japan.” Bodylore: Gender, Sex, Culture, Folklore, and the Body. February 28 2018. Web. <https://sites.wp.odu.edu/bodylore/2018/02/28/inked-and-exiled-a-history-of-tattooing-in-japan/>.

Lineberry, Cate. “Tattoos: The Ancient and Mysterious History.” Smithsonian.com. January 1 2007. Web. <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/tattoos-144038580/>.

PBS. “Skin Stories: The Art and Culture of Polynesian Tattoo.” PBS Thirteen. 2003. Web. <https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/>.

Additional Content

https://www.pbs.org/skinstories/history/

https://sites.wp.odu.edu/bodylore/2018/02/28/inked-and-exiled-a-history-of-tattooing-in-japan/