Today’s post comes from Hannah Cho, class of 2018 and Art Center multimedia assistant.

The Art Center’s most recent exhibition features beautiful medals and posters from the Great War

Category Archives: Site Feed

Bioarchaeology Helps Shed New Light on Ancient Mysteries

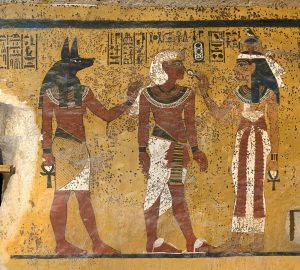

Since Howard Carter unveiled the tomb of the ancient Egyptian Pharaoh Tutankhamen in 1922, the world has been fascinated with the king. One major question surrounding Tut is the circumstance of his sudden death. Using bioarchaeology, archaeologists may have found a conclusive answer.

From examining Tut’s body along with written records, it’s evident that Tut died around 19 years old and his burial was rushed and unexpected. The tomb is small for a pharaoh, so Egyptologists speculate that it wasn’t originally intended for Tut, but they needed to bury him quickly (more on this that may lead to new discoveries in the link at the bottom). Bioarchaeology confirms Tut’s hurried burial. Mold-like spots appear on the tomb walls, and comparison of old and new photographs prove they haven’t changed since 1922, suggesting the spots are ancient. Recent microbial analysis confirms this by showing that the spots contain melanins, a sign of the metabolism of fungus, but no living microbes were found. The environment of the walls’ wet paint combined with foodstuffs buried with Tut would’ve created the perfect environment for microbial growth, resulting in the spots.

What could be the reason for Tutankhamen’s early and unexpected demise? Many have speculated about murder, a chariot accident, and even an unfortunate hippopotamus encounter. However, the bioarchaeology tells a much less dramatic story. Previously, the chariot accident was the leading theory on Tut’s death, as some chariots were buried with him and according to his mummy’s early CT scans, he suffered a fatal blow to the head. Bioarchaeologists debunked this theory when they determined Tut’s head injury was post-mortem (after death), probably sustained either in the mummification process or the mishandling of the body by Carter’s team. Also, bioarchaeology reveals from new CT scans that king Tut couldn’t even stand on a chariot, let alone ride one, as he had a clubfoot. In his tomb, archaeologists found 130 used walking canes, supporting the analysis that Tut needed a cane to walk.

The reason for his deformities? King Tut was born out of incest. Genetic testing of Tut and other mummies confirms that his father and mother were full siblings (further details of this found in the link at the bottom). While incest to keep the royal bloodline pure was not uncommon, it could have disastrous effects for the offspring, like Tut.

A 3-D rendition of what Tut would’ve have looked like during his lifetime, based on updated and extensive CT scans of his mummy

A clubfoot and an incestuous birth wouldn’t have been enough to kill Tut, but it would’ve weakened his immune system. Bioarchaeology’s analysis of Tut’s body found signs that he contracted malaria, possibly many times during his life. Tut possibly had some immunity to malaria because of his geographical location, but with Tut’s weakened immune system combined with a leg fracture (with possible complications), it’s likely that the disease killed him.

Pop culture depicts King Tutankhamen as a mysterious king under a golden mask who tragically died young, but bioarchaeology shows the real picture: a deformed teenager, barely able to walk, suffering from malaria and the effects of incest.

Sources:

http://www.livescience.com/14525-spots-tut-burial-rushed.html

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/newest-king-tut-theory-he-suffered-severe-disorders-due-inbreeding-180953113/

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/02/100216-king-tut-malaria-bones-inbred-tutankhamun/

Further details of genetic testing: http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/print/2010/09/tut-dna/hawass-text

Further Reading:

On the Life of Akhenaten (Tut’s likely father): https://www.britannica.com/biography/Akhenaten

On the debate of hidden chambers in Tut’s tomb: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/05/160509-king-tut-tomb-chambers-radar-archaeology/

Image Sources:

Tut’s tomb southern wall: http://www.livescience.com/images/i/000/017/169/original/king-tut-spots-2.jpg?interpolation=lanczos-none&downsize=*:1000

Tut body recreation: http://www.archeolog-home.com/medias/images/dnews-files-2014-10-king-tut-reconstruction-141020-jpg.jpg

My Friends at the Museum – Art that Speaks

Today’s post comes from Bella Dalton-Fenkl, class of 2020 and Art Center Student Docent.

I remember one day last term when I arrived at the Art Center and was met with a surprise—I had to give a tour to fifty people

Diet of Australopithecus Afarensis

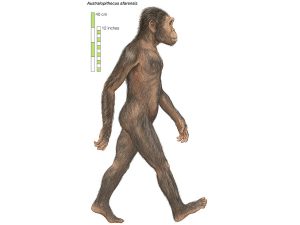

Australopithecus afarensis, more commonly known as “Lucy’s species” after Lucy, the famous fossil discovered in Ethiopia in 1974, is an early human species that lived between 3.85 and 2.95 million years ago in Eastern Africa.

An artist’s rendition of Au. afraensis. Males had an average height of 4 ft 11 and an average weight of 92 lbs, while females had an average height of 3 ft 5 and an average weight of 64 lbs.

A crucial part of understanding Au. afarensis is understanding the specie’s diet and therefore environment, as the environment determines what food is available. To determine the eating habits of Au. afarensis, researchers turned to morphological features relating to diet, such as skull and mandible (jaw) structure and teeth. Based on their strong and robust skulls, large mandibles, and thick enamel, some concluded that Au. afarensis ate hard and brittle foods. However, later studies found that while Au. afarensis could eat these foods, their diet actually consisted of softer foods, mainly grass, leaves, and fruits.

One group of researchers conducted a microwear texture analysis on the teeth of various Au. afarensis specimens. Different types of food interact differently with the teeth, leaving distinct textures and abrasions on the surface. Hard and abrasive foods like nuts and seeds create complex patterns, tough foods such as leaves leave long, narrow scratches, and fruits leave pits. From the patterns left on the teeth, researchers were able to determine what types of food the individuals ate. The results showed that Au. afarensis preferred softer foods such as leaves, grass, and fruit to that of hard and abrasive foods.

Another study came to similar conclusions using stable isotope analysis, a technique that involves analyzing the ratio of carbon in tooth enamel from two categories of plants: one of herbs, trees, and shrubs, and another of tropical grasses, sedges, and succulents. The results suggest that Au. afarensis ate more tropical grasses, sedges, and succulents, a consumption pattern that differs from that of earlier species who tended to avoid these foods.

Although researchers now have a fairly clear idea about the diet of Au. afarensis, the questions still remain as to why they ate softer foods when their morphology suggests that they were able to consume tough foods, and why they expanded their diets to include more grasses and sedges. One theory proposes that Au. afarensis used hard foods as a “fallback” in seasons when softer foods weren’t available. Others suggest that their expanding diets were a result of fluctuations in the environment, and that their ability to eat hard and soft foods allowed them to survive short and long-term climate fluctuations and corresponding changes in available resources. However, other researchers disagrees, claiming that the change in diet was instead due to the species exploiting a larger range of resources in a broader mosaic of habitats including grasslands, woodlands, and wetlands.

More studies are needed to determine which theory is most accurate. The case of Au. afarens’ diet is a prime example of how multiple methods of analysis are necessary to gain an understanding of the past. Additionally, it shows the changing nature of our historical understanding and how new methods and techniques can provide further insight and better knowledge than previously attainable.

Further Reading:

- http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0047248404000508

- http://johnhawks.net/weblog/reviews/early_hominids/diet/ungar_2005_occlusal_relief_diet.html

Sources:

- http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-fossils/species/australopithecus-afarensis

- https://phys.org/news/2009-10-ancient-lucy-species-ate-diet.html

- http://www.pnas.org/content/110/26/10495.full

- http://www.pnas.org/content/97/25/13506.full

Images:

Mammoths and Archaeology

History of Mammoth Breeds

Throughout the course of time, there have been a few different types of mammoths. About 1.8 million years ago, a breed of mammoth known today as the southern mammoth crossed into North America via a temporary land bridge in the Bering Strait. The Columbian mammoth was also a prevalent breed in North America, with its range covering the present-day United States down to Nicaragua. The smallest of the mammoth species was the woolly mammoth. A little over 100,000 years ago was the first time they were able to get to North America, again via the Bering Strait land bridge. Archaeologists know the migration patterns based on the ages of skeletons and fossils that are found across the globe.

What We Know About the Mammoths

Much of what we know today about the woolly mammoth comes from their teeth. The aforementioned breeds of mammoths were only able to be differentiated because of variations in their teeth. For example, the woolly mammoth had the most enamel ridges in order to protect its teeth from the abrasive grasses it consumed. Scientists at the Natural History Museum in London used a micro-CT scan to map the changes in mammoth teeth throughout their lifetimes based on the microscopic features on worn down enamel.

Reasons for Extinction

There are three ways archaeologists believe that the woolly mammoth met its demise. The first is from human interference. For humans living during the Pleistocene era, woolly mammoths were a source of meat, thick hide, fur, and bone. It would have only made sense for humans to kill as many mammoths as possible. The second belief is that the woolly mammoth went extinct because a large meteorite or comet struck the Earth. This would have also caused a mass extinction of many other animals as well. The third belief is that climate change shrunk the woolly mammoth’s territory so quickly that the beasts could not adapt to the warmer climate quickly enough. The changing climate has been affecting populations of animals for millions of years, so this hypothesis is the most plausible.

Can We Bring Them Back?

Within the last few years, news headlines have been talking about the possibility of cloning a woolly mammoth. In 2013, archaeologists uncovered a well-preserved woolly mammoth from a peat bog in Siberia. The contents of its stomach contained grassland plants such as buttercups and dandelions, so the animal was nicknamed Buttercup. After just a few tests, archaeologists were able to find blood oozing from Buttercup near her elbow. The blood told a lot about Buttercup, but so far an undamaged strand of DNA cannot be found. Cloning is temporarily out of the picture. The best that science can hope for is to combine DNA from Buttercup with that of elephants, essentially creating a new breed of mammoth.

For Further Reading

- http://www.livescience.com/50275-bringing-back-woolly-mammoth-dna.html

- http://www.techtimes.com/articles/161859/20160531/40000-year-old-juvenile-mammoth-named-lyuba-gets-featured-in-canadian-museum.htm

Sources

- http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mammal/mammoth/about_mammoths.html

- http://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/science-news/2015/november/north-american-mammoth-origins-rewritten.html

- http://www.nationalgeographic.com.au/history/why-did-the-woolly-mammoth-die-out.aspx

- http://www.livescience.com/48769-woolly-mammoth-cloning.html