Many cities in California don’t use water sources from where they’re located, but instead pull resources from different regions. This is truer for Los Angeles than most cities. With its large population, location near saltwater, and drought conditions, Los Angeles relies on fresh water from miles away. LA’s use of outside water sources not only puts people out of their homes, but also takes water from outside areas. Through the study of where water is from and how it changes the landscape, we can further ask the question if it is alright to take water from outside sources to fuel a city.

The original aqueduct built to sustain Los Angeles was the Zanja Madre, in 1781 on the L.A. River. In the 1800s, Judge William Dryden was hired to build a more elaborate water system in the middle of the Los Angeles Plaza. Dryden then became the head of the Los Angeles Water Works Co. and after his water system flooded, the water company got passed on to another private owner, and then eventually to city ownership in 1902 as the L.A. Water Department.

The Los Angeles Aqueduct project began in 1905 and was completed in 1913 diverting the Owens River into a canal that flows into the the Lower San Fernando Reservoir. This effectively destroyed Owens Valley, which was a prospering farming community. The ownership of this land was made through deceptive moves and insider information, which eventually led to the California Water Wars. The water that was being taken from Owens Valley was being fed into Los Angeles and the San Fernando Valley, but none was saved for the people living in Owens Valley.

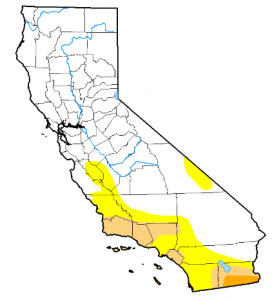

Currently, Los Angeles gets water from San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta, Colorado River, Eastern Sierra snow melt, local groundwater, and desalination. The only somewhat local resources are local groundwater and desalination. The sad part is that these supply the least amount of water to Los Angeles even though they are the closest to Los Angeles. Snow pack and the San Joaquin-Sacramento River Delta provides nearly 95% of the water to southern California. The issue is taking water from other places. Other states are affected due to California’s use of the Colorado River and extreme reliance on the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

With Los Angeles’ continual population growth more water is being funneled hundreds of miles to reach the metropolitan area. Luckily for Californians, most of California is out of the drought or in less severe drought levels, but that doesn’t mean they need to stop conserving. As someone from San Diego, we need to keep up initiatives to reduce water consumption and look for alternative water sources. Desalination is becoming an option, but still uses too many resources and money to be viable. If people want to continue consuming large quantities of water, the best answer might be to move out of desert and temperate climates.

Further Readings: http://waterandpower.org/museum/Water_in_Early_Los_Angeles.html, http://www.cadrought.com/southern-california-gets-water/

Sources: http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Home.aspx, http://www.owensvalleyhistory.com/, http://www.history.com/topics/los-angeles-aqueduct

Image Sources: http://droughtmonitor.unl.edu/Home/StateDroughtMonitor.aspx?, CAhttp://a.scpr.org/i/9dd3c84ad1a3286fb9d46206d4fa4acb/70909-full.jpg