Jenny Magnes (Physics) and Mary Ann Cunningham (Geography)

Photos: M.A. Cunningham

In July 2017 we visited Hamburg, Bremen, Bremerhaven, Frankfurt, and Darmstadt, in preparation for an Environmental Studies course on Renewable Energy in Germany (ENST 254, Environmental Science in the Field). The trip provided a lot of insights for the class, but we also found some themes that are broadly relevant for other sustainability and climate action efforts at Vassar. Among these are 1) the importance of high-efficiency buildings and 2) the potential of an energy transition working group.

- Passive buildings are increasingly standard

Following visits to the Frankfurt Energiereferat and Passive House Institute (PHI), Darmstadt (near Frankfurt)

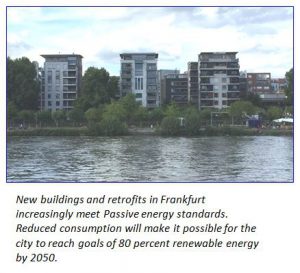

Reducing energy demand is a critical first step needed to make renewable energy economical. Therefore, since 2007, all new city-owned buildings in Frankfurt must meet passive standards of < 15 kWh/m2 per year. This is only about 10% of standard buildings in Germany. In addition, the city is aggressively promoting retrofits of existing buildings. A number of European cities are adopting similar policies. Key ideas are outlined in these slides from Dr. Berthold Kaufmann at the Passive House Institute, but these are some primary means for reducing energy consumption:

- Well-insulated, air-tight buildings with mechanical ventilation (to provide fresh air, with a heat exchanger to control gain or loss of heat from the building) and humidity control to reduce over-heating and over-cooling needs associated with indoor humidity;

- Strategic use of windows placement, shading, and other design components to control or promote solar heat gain;

- Electrical heating (rather than boiler steam/hot water) if heating and cooling is needed;

- Solar panels on roof surfaces to produce electricity.

By 2020 (only 3.5 years from now) all new city-owned buildings in Frankfurt must be energy-plus, that is, producing more energy than they consume for heating, cooling, hot water, and electricity.

Some key mechanisms for enacting these policies above include these approaches:

- Use of life-cycle cost accounting—as though the intent is to occupy a building for at least 20 years;

- Have many parties at the table from the start of a building or renovation project—trades and mechanical operators, architects, lenders, owners, builders and contractors, material suppliers—so that different players avoid undermining each other’s work or goals;

- Facilitate financing by making clear to lenders that, although high-efficiency buildings are not familiar, the reduced operating costs make them safer and more reliable investments compared to business-as-usual construction practices;

- Communicate with users and constituents to make sure the principles of sustainable building are well understood and accomplishments are acknowledged.

Dr. Kaufman at the Passive House Institute (PHI) noted that renovating to high energy standards is more expensive than building new—perhaps 1.5 times as much in Frankfurt, so standards for renovated old buildings tend to be lower than for newly built structures. However, he also noted that for a total renovation of an older building in the Frankfurt area, the basic energy upgrade (to meet code) might cost about 200 euros/m2, and a passive-standard retrofit might cost 300 euros/m2; but the total cost of building renovation is generally around 1200-2000 euros/m2 (note that these are ballpark values to indicate relative magnitudes). So while the absolute cost of a high-standard energy retrofit is higher, the relative cost, compared to other renovation costs, may not be extreme, and the lower operating costs can produce net savings in a few years.

Building to these standards in Germany, including negotiating with architects, owners, lenders, and other parties, still takes effort, but it is getting easier because German builders and architects have been developing passive-standard building since 1991. Also cities and states are increasingly incorporating these standards into building codes, just as LEED standards are increasingly influencing building codes in the U.S. (Note that LEED standards are based on a variety of measures and do not have specific energy performance criteria as Passive standards do.)

There are many resources in New York City and New York State on which we could draw to improve our understanding of and planning for passive-standard (or high-efficiency) renovation. Speakers, workshops, and field trips should all be pursued this year.

- Collaboration facilitates research and teaching on renewable energy

Jacobs University, Bremen

Jacobs has faculty with expertise in a variety of topics relating to energy and climate. In a number of cases, faculty have formed working groups that coordinate activities and encourage sharing of ideas and projects. While there are a variety of working groups at Vassar, we would do well to consider forming and supporting an energy transition working group that could focus on 1) research in support of teaching that relates to energy and climate, 2) research relating to the energy transition called for—but not detailed—in the 2016 Climate Action Plan, and in the 2017 Campus Master Plan.

The 2017-18 energy master planning project, funded by NYSERDA, includes an advisory energy planning team, which is a good start toward this broader working group. In addition, a working group could engage research, teaching, and publication, which would help reward faculty and students and maintain their interest. More broadly, a working group should draw together staff, administrators, students, and faculty in a common conversation about Vassar’s energy future and climate impacts. Insights from a variety of disciplines and a variety of roles on campus should improve the effectiveness of academic and policy conversations.

The same strategy of getting all relevant actors into the same conversation is also a central component of climate and energy strategies for the city of Malmo, Sweden, which plans to run on entirely renewable energy–wind, solar, and biogas (methane)–for all electricity, heating, and transportation by 2030. Malmo’s aggressive environmental plan emphasizes that every committee and steering board bears responsibility for achieving the objectives of the sustainability plan, and that each committee is responsible for annual accounting of its progress.

A working group on Vassar’s energy transition would be most effective if it had a presidential directive. Presidential pressure would improve the likelihood of follow-through on any recommendations the working group produced–since few of us can afford to waste time on fruitless discussion. Since it takes time and experience to learn new strategies, the sooner such a working group is established, the more likely Vassar is to meet the goals outlined in the Master Plan.