It’s Time to Work on Climate

A Summary and Response to Professor Joshua Tan’s Lecture at Vassar College on Wednesday, September 16, 2020.

By Maya Pelletier

“I haven’t seen you in forever” (actually, I saw you last week). “We got dinner the other day” (well, maybe it was two months ago). “I’m coming–I’ll be there in a second” (no, you’ll be here 20 minutes late). These examples direct us to the questions of time. What is time? How do we understand it? What implications does this understanding have, particularly in respect to conceptualizing climate change? Professor of physics Joshua Tan virtually visited Vassar (say that five times fast) on Wednesday to talk with students about “making sense” of time.

According to Tan, physicists think of time “as a coordinate:” something you can measure. Ancient civilizations, such as the Aztecs, studied the sky and were able to identify accurate, reproducible patterns of the sun’s angle that led to the measurement of years. Today, Modern physicists rely on cesium clocks to determine the standard duration of a second. Both of these methods of measurement represent a standardization of time that we can use to contextualize events that happen around us. We formulate timelines of events that may range from a few seconds to days, weeks, or years.

Humans and other organisms have innate senses of time, too, that differ from the incredibly accurate astronomical and quantum measurements provided by physics. You probably get hungry around the same time every day, or wake up at a similar hour, two examples of your innate sense of time keeping your body functions in check. Interestingly, as we age, our perception of time changes too. When you’re 30, 30 years seems long: it’s the entirety of you existence. Then, when you’re 60, 30 years isn’t quite as much: now it is only half your life. Finally, when you’re 90, 30 years is even less time: just a third of your life.

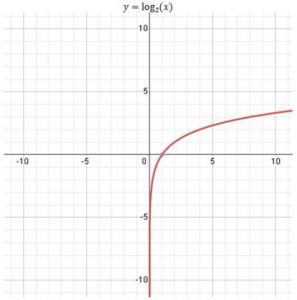

This change in the perception of time behaves in a logarithmic fashion. What does that mean? Well, let’s look at the graph pictured below. The red line rapidly increases at the beginning but then begins to level out. Our perception of time is the same: at the beginning of our lives, one year is a much larger percentage of time relative to our age, and we therefore perceive it as much longer than we might later on.

So, how does any of this relate to climate change? Great point. Humans are pretty good at understanding seconds, hours, days, weeks, months, and years in the context of our lives or even of our civilizations. For most of us, however, this understanding falls apart when we think about times that are longer than a few hundred years. For example deep time (geological time) deals with intervals of years so large that most of us can hardly wrap our heads around them.

This poses a problem. Without fully understanding the magnitude of deep time, we can look at recent climatic changes since the industrial revolution and compare them to past events that occurred over periods of tens of thousands of years. Creating this illusion of a historical precedent for the changes we are seeing in climate today is not only incorrect, it is dangerous.

When we write off climate change from industrialization as part of a historical pattern, we blind ourselves to the magnitude of the damage humans (primarily western, white, industrialized societies) have caused to earth systems. The reality is that present climate change is happening faster than any other climatic change we have been able to measure. Nothing about this situation is normal. The relatively stable planetary conditions our civilizations evolved in are ending; the present is no longer being played on the same field as the past, and that is significant for formulating our approaches to the future.

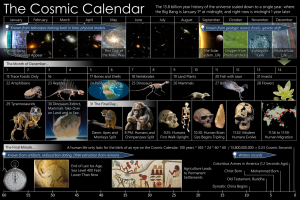

Before we can get to thinking about the future, however, how can we think about the present? How can we conceptualize our own existence in terms of the age of the universe? Joshua Tan has an answer: scale deep time to a unit that we experience and understand, like a year. This means taking some unit of time, the age of the universe for example, and representing it as 365 days. We can then think about events like the formation of earth and the beginning of life in terms of what month/day during the “year of the universe” they occurred.

For example, according to Tan when we scale the age of the universe, we get this: earth formed in September; oxygen dependent life arose in October; eukaryotic cells came in November; multicellular life arrived in December; the dinosaurs lived from December 25th to the 29th; the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs hit on the 30th; humans evolved on the final day, and the modern humans only at 11:52 pm on that day; the great human migration spreading people across all continents happened from 11:56 to 11:59 pm; and one human life is less than a quarter second.

Thinking about climate change in this framework gives weight to the speed with which we are experiencing change. We can look at data of historical changes in climate and see that present patterns do not match them at all. This disconnect between past and present calls into question every model we use for conjecturing the future. Significant uncertainty related to the impacts of climate change is inevitable, and we must understand that, as Tan puts it, “uncertainty cuts in both directions.” Just because scientists can’t say exactly how bad climate change will be doesn’t mean we can ignore it. The events of today are already worse than many predictions made 20 years ago.

We literally stand between a fire and a flood: from one side flames race toward us and from the other, waves. It is time to stop arguing about how long we have to react. We cannot wait: let’s get to work.

Author:

Maya Pelletier

Environmental Studies

Vassar College class of ‘22

Grand Challenges Student Catalyst

Featured image: https://www.amazon.com/VVIEER-Clock-Silent-Ticking-Picture/dp/B087X55144

Image 1: https://study.com/academy/lesson/basic-graphs-and-shifted-graphs-of-logarithmic-functions.html

Image 2: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmic_Calendar