Exhibition on View in the Main Reading Room of the Vassar College Art Library

March 6 – April 20, 2015

For the next several weeks the Art Library is privileged to present to the Vassar community an exhibition of artists’ books entitled “Misbehaving: Artists’ Books by Women Artists,” on view through April 20. All but one of the works in the exhibit are from the personal collection a visionary librarian and curator who helped to establish the artist’s book as a significant art form, former Walker Art Center librarian Rosemary Furtak, who passed away in 2012. Among these are works by many artists who have contributed to conversations about the role of women in art and society in recent decades, including Ida Applebroog, Barbara Kruger, Joan Lyons, Laurie Simmons, Jessica Diamond, and Kiki Smith. Collectively these works provide a window into the development of the artist’s book from its early days in the 1960’s and 70’s through to the present. They also illustrate the medium’s gradual incorporation into mainstream museum culture and its literature, thanks in part to Furtak and a small handful of art librarians who followed her lead as a collector and early proponent of the genre.

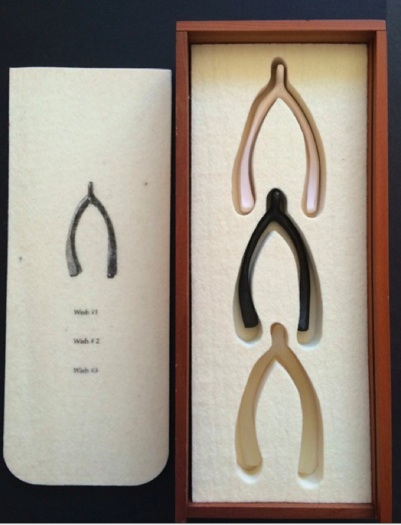

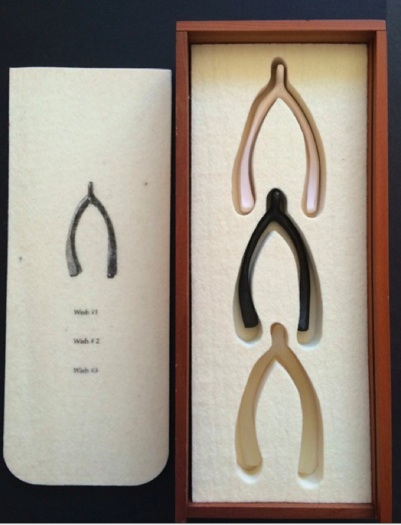

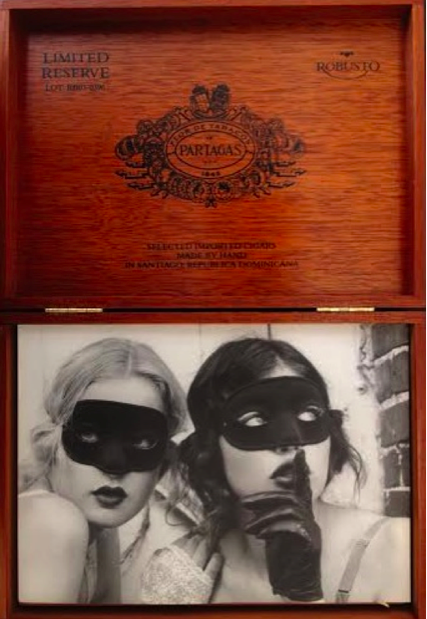

III (3 Wishbones in a Wood Box). Lorna Simpson. Mixed media, 1994.

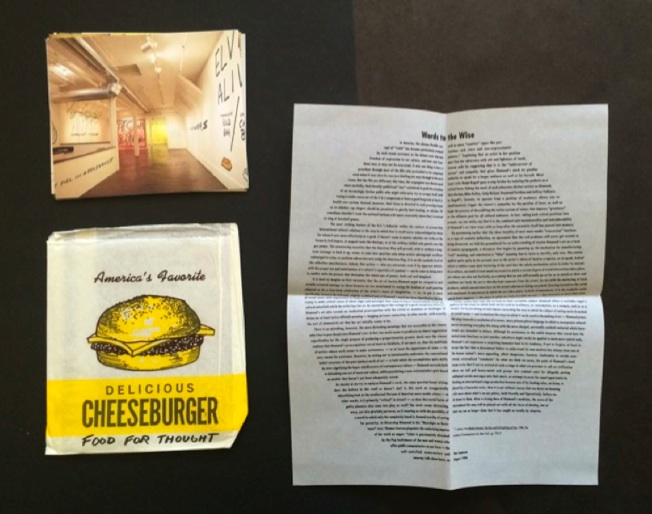

As Grace Sparapani (VC’16), who curated “Misbehaving,” writes in the exhibition brochure, just what an artist’s book is as a category “is hard to pin down,” and is sometimes defined by negation: “whatever isn’t anything else,” in the words of the feminist critic Lucy Lippard. Librarians and museum curators found artists’ books strange, and were perplexed as to what to do with them. To curators, although many were being produced by artists who worked in traditional media such as Ed Ruscha and Sol LeWitt, the works seemed unexhibitable and, produced in editions of many copies as multiples, purposely designed to undermine the cult status of the art object and the economics of the art market in their low cost and modest formats. To librarians, they seemed difficult to use and to integrate into conventional collections. Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations, for instance, was often classified and shelved with books about transportation. Furtak captures something of the crux of the problem in her own definition of an artists’ book: “An artist’s book is a book that refuses to behave like a normal book.”

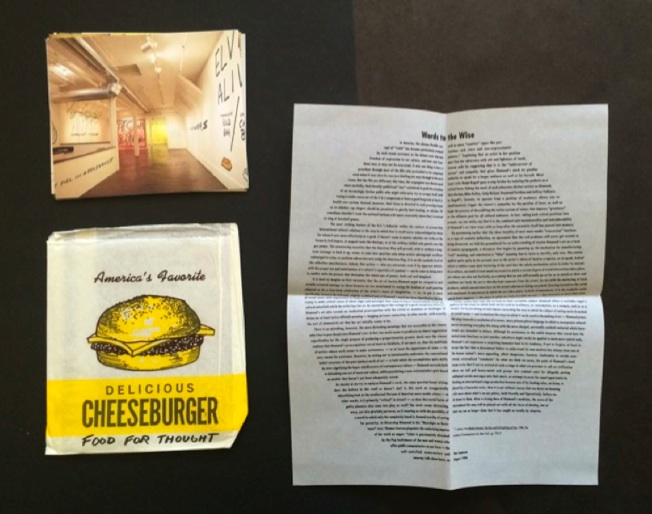

Food for Thought. Jessica Diamond. Mixed media, 1990.

When she arrived at the Walker in 1983, Furtak discovered the museum’s handful of artists’ books had indeed been placed in museum storage, unlikely to ever be used or exhibited. She “liberated” (her word) these misbehaving books from isolation and obscurity and brought them into her library. In accord with conceptual artists of her generation such as George Maciunas and Lawrence Weiner (whose “BITS AND PIECES PUT TOGETHER TO FORM A SEMBLANCE OF A WHOLE” graces the current facade of the Walker), Furtak addressed the problem of the artist’s book by deploying them just as its early makers understood the work of art itself: as bearers of conversations that artists conduct with one another and with whomever else may be listening. She therefore treated them as living documents by giving them face time with the other art books on her library’s shelves, incorporating them into the library collection and exhibiting them on empty shelves and tabletops, and eventually her extraordinary exhibit case (see Flickr), wherever and whenever she could. In doing so she demonstrated that artists’ books could be integrated into a conventional collection as usable documents, and also that artists’ books could make interesting and visually striking exhibits.

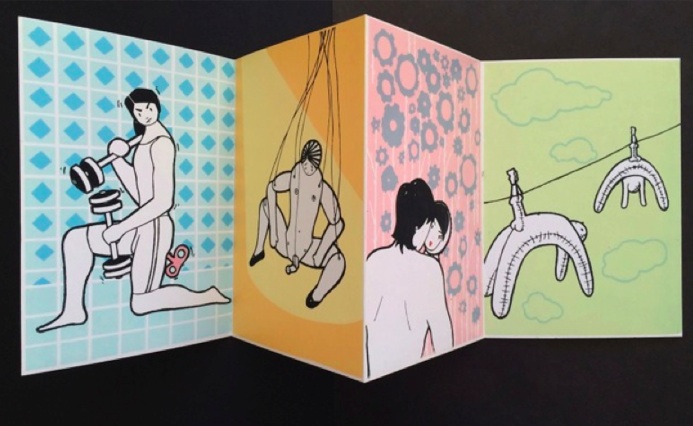

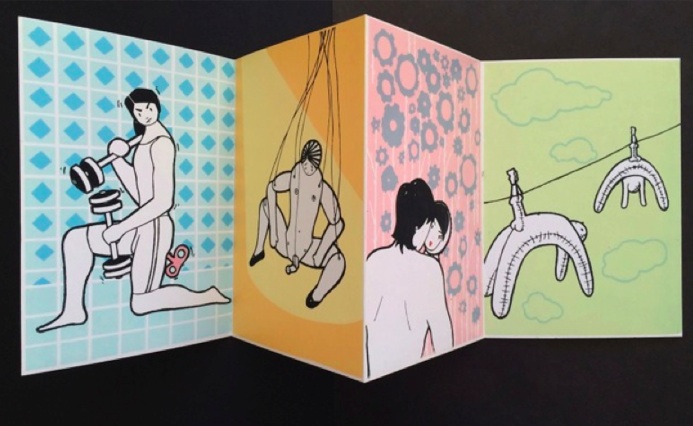

Plegable. Adislen Reyes Pino. Ink on folded board, 2005.

Furtak also began adding avidly to the collection. Beginning with a check of $500.00 given to her by Sol LeWitt as a start-up stimulus, she gradually built up one of the most important museum collections of artists’ books in the world. And as Walker curator Siri Engberg describes, Furtak’s library was soon transformed from a “quiet corner in the building” into the institution’s “nerve center,” and a place of connection and discovery for artists, curators, and other researchers. During the same period the Walker gained a reputation for being the most dynamic and influential exhibiting institution devoted to modern and contemporary art in the United States, and a nursery for innovative, risk-taking curators and directors who would go on to become forces in the art world generally, including Kathy Halbreich (MoMA), Philippe Vergne (L.A. MOCA), and Peter Eleey (PS1), who once stated he got his best ideas in the Walker library. In recent years the artist’s book has come to acquire a kind of celebrity status in the museum world, with modern and contemporary museum exhibits regularly including vitrines with examples of the genre, and with so many established artists producing them.

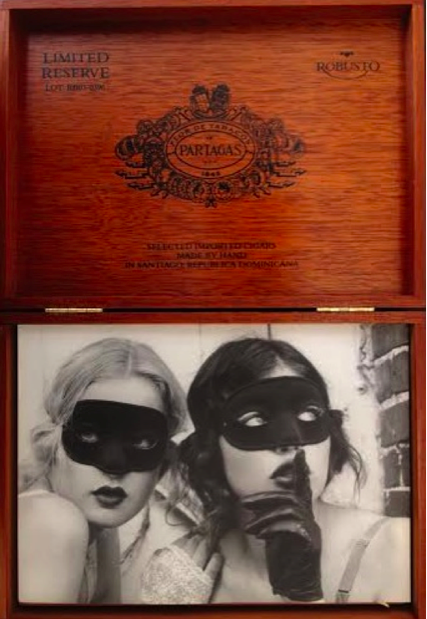

Assemblage. Rosemary Furtak. Mixed media, 2003

Many if not most of the works in “Misbehaving” testify to a conscious identification between the early outsider status of the artist’s book and the outsider status of women in the art world, and in the culture in general. Little wonder that a genre that is edgy by nature and that had its origins in subverting conventional currents of verbal and material exchange should be taken as an expressive medium by a group of artists whose voices are usually treated as out-of-place: sometimes tolerated but rarely supported or celebrated. Furtak’s own piece, “Assemblage,” which forms the centerpiece of our exhibit, is emblematic here. A readymade composition of found objects, the work consists of an otherwise empty cigar box containing an invitation to an Ellen von Unwerth exhibition depicting two fashionable and bare-shouldered young women. Both women are masked and show a gloved hand, one of lace and the other of leather, the latter with an index finger to her lips suggesting secrecy and misbehavior. The whole forms a kind of clasped book with a surprise inside: the surprise of women discovered hiding in a man’s space, the last place a man might expect to find them, and, perhaps, in this context, a reformulation of the librarian’s stereotypical shush. The piece more than holds its own with the other works in the exhibit, and silently speaks volumes about those works, about the place of women in the world in general and the art world in particular, and about Furtak’s own professional practice. For the space in which she created her library and her own influence upon the art world was much like this cigar box. Furtak was not openly supported by her institution in her artists’ book collecting. To create the collection she had to divert, somewhat surreptitiously, money from her annual book budget to buy artists’ books, so that, essentially, over a period of twenty-nine years she built the entire collection by scrounging. Furtak was never given curator status, and paid poorly even for a librarian, which as a women’s profession is traditionally undercompensated. To make ends meet she spent the early part of her career babysitting on evenings and weekends, often for the Director who hired her. Later she worked a second job as an usher and finally coffee-bar attendant at Minneapolis’ Symphony Hall.

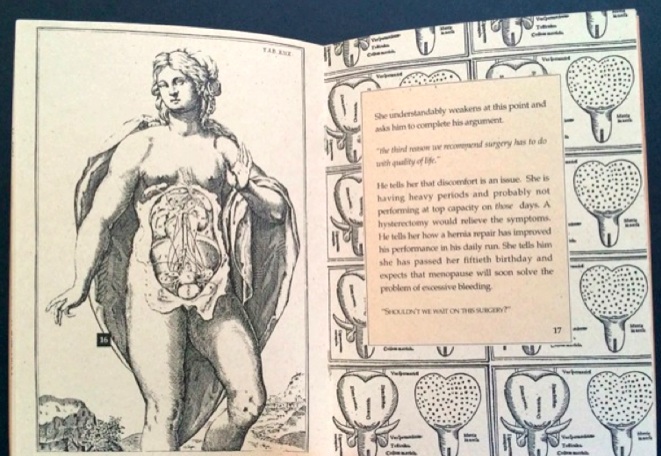

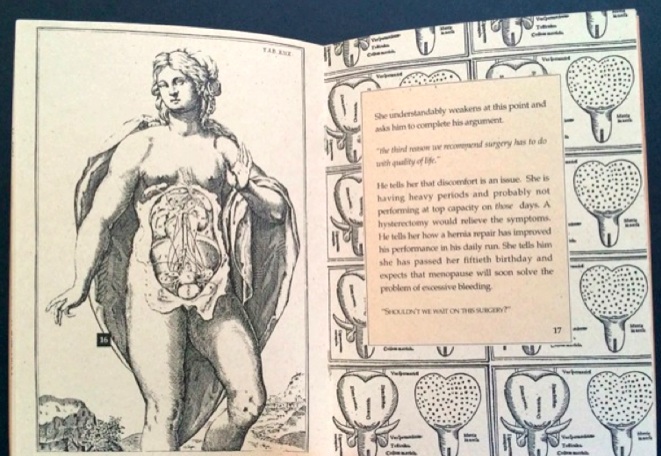

Gynecology. Joan Lyons. 1989.

Small wonder then that in her personal collecting Rosemary Furtak acquired so many works by women artists, under-represented and so often, like herself, practiced in hiding their accomplishments in plain sight. Collectively the works in this exhibit remind us that we can aid and influence others and accomplish much good even in the context of such constraints, that the cultural conversations that determine how we engage the world and one another can be carried forward, even if spoken in low tones and in spaces we occupy only marginally, perhaps toward the eventual unraveling of these limitations. Most of the works on view in this show are destined after its closing to go into the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C., an institution devoted to deploying and promoting art by women toward just this outcome.

Thomas Hill,

Art Librarian

![Closeup of page 1, Anthony, Susan B. -- to William Lloyd Garrison, [Mar 8, 1859]](http://pages.vassar.edu/library/files/2015/03/vassar46740-290x290.jpg)