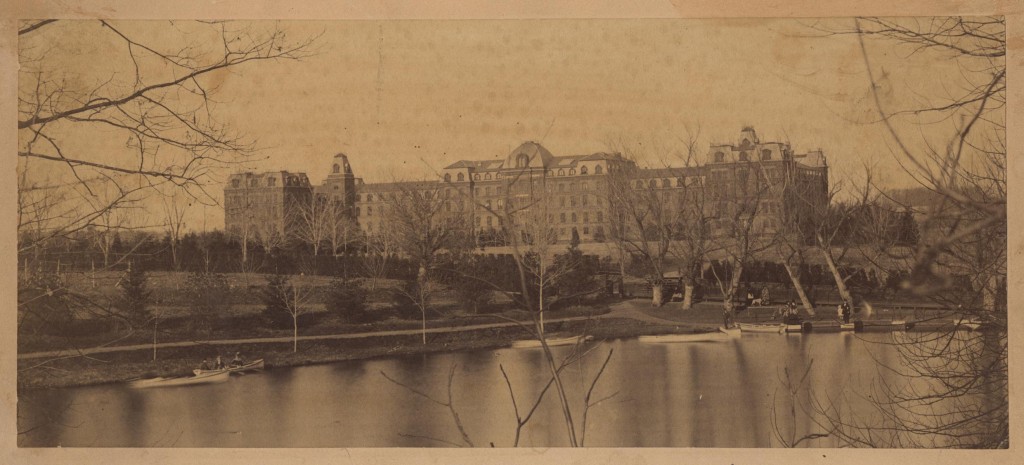

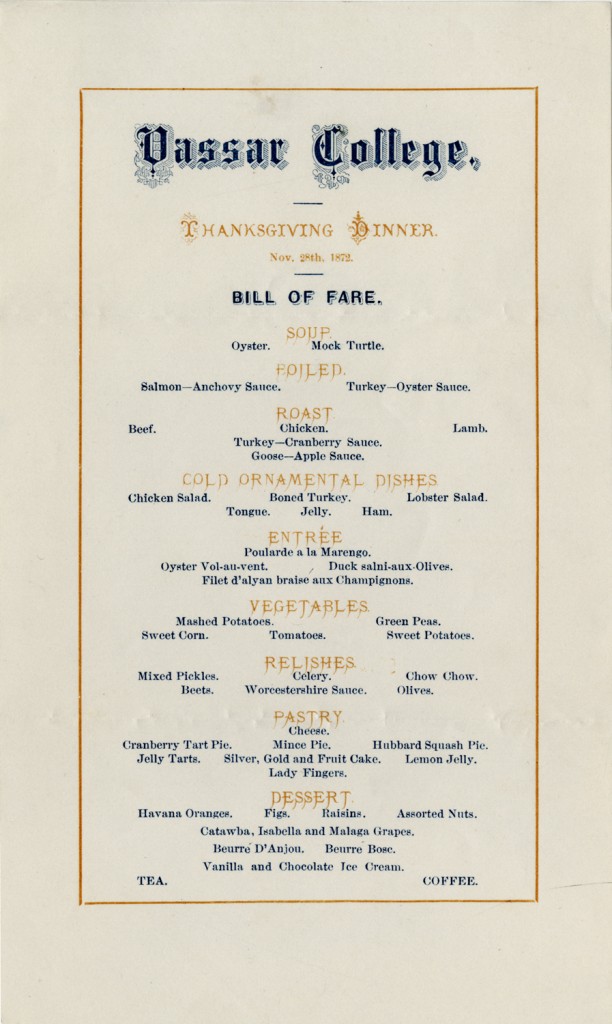

Last year we shared a collection of menus from Vassar Thanksgivings past. This year we’re moving beyond the food to offer an account of how Vassar students spent the full holiday nearly 140 years ago, from dawn to dark. The piece appeared in the January 1873 issue of the Vassar Miscellany.

Thanksgiving Day dawned clear and bright upon us. That is to say, although we can not assert this for a fact, not having made any personal observations in the matter, it is safe to suppose that a perfect dawn must have preceded the perfect day which followed. The air blew fresh from the far-away mountain-tops, with a dash of snow and a tingle of ice in it that was particularly exhilarating. The sun did his very best beaming, the sky intensified its blue, and the clouds piled up their fleeciness. If we had not such an extreme dislike to anything which savors of originality, we might have been led to exclaim, “O, what is so rare as a day in November!” As it was, we bit our lips, and kept the sentiment in its proper place.

The half-past eight arrangement for breakfast was highly satisfactory to all parties. To tell the truth, the arrangement seemed much more satisfactory than the breakfast. But that was to be expected: for students are proverbial grumblers; and the occasional remarks overheard about “spreading things out” and a “consistent evenness” must have been the product of thoughtlessness or—the north side of the dining-hall. However that may have been, it was indisputably proved that “a short horse is soon curried.” Prayers after breakfast brought back “ye olden time,” and reminded us that Thanksgiving Day was not appointed for the sole purpose of eating turkey. Some, of us had difficulty in realizing this fact, and it required a great deal of logic to convince us; but in time we all assented to it.

As soon as practicable we joined the company of anxious and scribbling Juniors in the library, who were poring over Shakespeare and Lamb and Froude in a last desperate struggle with those eternal essays. Burying ourself in a corner, we proceeded to pound our head against a wall of books, hoping that such a performance would send ideas showering upon the paper. Judging from analogy and experience, we concluded that every other girl was doing about the same thing. As fast as a respectable number of ideas were thus knocked out, one after another departed, wearing that particular smile of relief which is especially exasperating to the captive ones.

For two hours or more before dinner the grounds were pervaded by people “getting up an appetite.” This was preparatory to “getting up a toilet,” and both objects were accomplished with a wonderful degree of success. To describe the former would be unkind; to describe the latter would be impossible. Behold us, then, O imaginative reader, seated in the dining-hall at half past three, each with her “own particular,” her best gown, best behavior, best smile, and best appetite. The dinner was gotten up in the very best style of our steward, and was as like the one of last year as anything well could be. Those brave individuals who began with the “intention of partaking of every dish, gave up in despair before half accomplishing their purpose. It was, indeed, rumored that one plucky damsel had achieved the glorious work, but she has not since been heard from. The question of time was clearly not involved in the solution of this problem, for whatever in that line cannot be accomplished in three hours, is so infinitesimal that it may practically be disregarded.

We draw a veil over the hour that followed. Enough to say, that at its expiration we seated ourselves in chapel to listen to readings by the President. His kindness in reading to us was only exceeded by the excellence of his elocution. The selections were from the “Merchant of Venice,” and included nearly all the favorite scenes.

Miss Terry received in the parlors till nine o’clock, when we mustered our forces tor a fresh attack in the dining-hall. All things considered, the victory which we achieved was marvelous. We accomplished all that could reasonably have been expected of us.

The spirits of just men made perfect, held undisputed sway over the house that night. Our ancestors from time out of mind passed in solemn procession before our astonished vision. Ghosts of long-forgotten friends with mournful visages, shook the finger of reproach at us. Hollow-eyed children, imps of darkness, weird and fantastic forms, floated around our pillows, and the air was full of heavy oppression. Night was eternal; the sun had set forever; the firmament was a blank; existence was just becoming utterly unbearable, when a vigorous shake from our room-mate recalled our wandering wits.

However blessed the man who invented Thanksgiving may be, the demented individual who got out a patent on the day after, should have been forced to leave the country.

You can read this account in its original form on pages 124-126 of the Vassar Miscellany, January 1873.