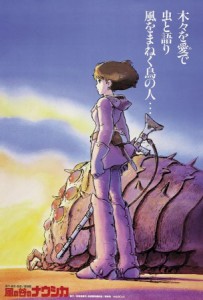

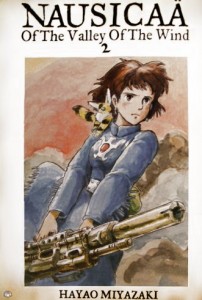

Critically acclaimed Japanese film director, producer, screenwriter, animator, author, and manga artist, Hayao Miyazaki is no stranger to original, vibrant and brilliantly animated masterpieces. However, like in the case of many artists, outside inspiration inevitability inhabits his sphere of creativity from time to time. These instances filled with foreign inspiration are most noticeably portrayed in his animated film, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) (風の谷のナウシカ), a post-apocaplyptic tale of a young princess who becomes intwined in a struggle with Tolmekia, a kingdom that tries to utilize an ancient god to eradicate a poisonous jungle filled with giant mutant insects.

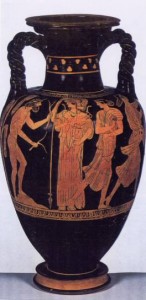

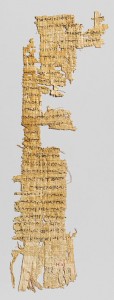

The foremost connection between Miyazaki’s film and Greek mythology is indeed the main character. It is not by pure coincidence that the main character identifies with the same name as the Phaeacian Princess Nausicaa (Ναυσικάα or Ναυσικᾶ) from Homer’s Odyssey. The bank of contemporary literature and entertainment that centralizes on Nausicaä is quite minuscule; it would be unbelievable to assume the inspiration sprouted from any other origins. In fact, Miyazaki first came across Nausicaä in Bernard Evslin’s Japanese translation of a dictionary of Greek mythology and fell in love with the character portrayed.

Even within the first few minutes of the film, Miyazaki exemplifies how Naussica’s personality and identity parallels to her counterpart’s in the the Odyssey. Similarly to the Odyssey’s Nausicaä who is the princess of the Phaeacians, Miyazaki’s Naussica is also the princess to her kingdom in the Valley of the Wind. The film opens with Nausicaä exploring the Toxic Jungle, a forest swarming with giant mutant insects and lethal fungi born from an apocalyptic war that destroyed civilization (pretty crazy, I know). Hearing explosives from the distance, Nausicaä springs into action, jumping onto her hang glider in order to find the source of the sound. She discovers Lord Yupa riding on his emu-creature steed, fleeing the wrath of an outraged ohm (a gigantic, trilobite-like creature, in case you didn’t know). Nausicaä acts as a compass and a savior to her human companion and does the same for the vicious insect that is chasing him. In the Odyssey, Nausicaä treats Odysseus with the same hospitality and respect when he washes up on shore. Odysseus begs Nausicaa for aid after being shipwrecked:

“So Odysseus advanced upon these ringleted girls,

Naked as he was. What choice did he have?

He was a frightening sight, disfigured with brine,

And the girls flutterd off into the jutting beaches.

Only Alcinous’ daughter (Nausicaä) stayed. Athena

Put courage in her heart and stopped her trembling.

She held her ground, and Odysseus wondered

How to approach this beautiful girl. Should

He Fall at her knees, or keep his distance

And ask her with honeyed words to show him

The way to the city and give him some clothes?

He thought it over and decided it was better

To keep his distance and not take the chance

Of offending the girl by touching her knees.”

While the other servants are scared away by Odysseus’ sudden appearance, Nausicaä, instead of running away, offers Odysseus clothes and leads him to the edge of the town with her mule cart. The mutant insects in Miyazaki’s film, like Odysseus, are ugly and disfigured monsters that become scared and helpless when they “wash” up on the shore of human civilization. While everyone else is horrified of these creatures, Nausicaä is the only one who feels sympathy towards them and has the courage to lead them back home to the Toxic Jungle. Although Miyazaki’s Nausicaa isn’t riding on a modest chariot (she has a handy air glider instead), Nausicaä excels in aiding both the homecoming of Lord Yupa to the Valley of the Wind as well that of ohm back to its home in the Toxic Jungle. Again, later in the film, with her soft words and bug charm (knick knack she carries around to communicate with bugs), she soothes an outraged, frightened and injured insect found in the destroyed Pejite plane and follows the bug home all night until it returns safely to home (To watch this particular scene click, here. Sorry, no youtube video available). In both Homer’s and Miyazaki’s version, Nausicaä is an invaluable asset and guidance to those searching for their way home.

Of course, Nausicaä, with her love for insects along with her strong warrior princess aura, doesn’t completely fit the description in the Odyssey. She is still her own original character of Miyazaki’s mind. Beyond partly playing the part of her Odyssey counterpart, she also embodies aspects of the Greek goddess Artemis. In the Odyssey, Odysseus describes her appearance saying:

“I implore you, Lady: Are you a goddess

Or mortal? If you are one of heaven’s divinities

I think you are most like great Zeus’ daughter Artemis.

You have her looks her stature her form.”

Artemis, being the goddess of wild animals (that includes insects; they are animals too), provides Hayao Miyazaki a perfect pathway to integrate other outside influences into his character. Specifically taking this opportunity to integrate the characteristics of the protagonist of a twelfth-century Japanese tale called The Lady who Loved Insects (虫めづる姫君), Miyazaki provides his Nausicaä with the same ability of befriending insects that the protagonist of the Japanese tale has. By doing this, Miyazaki combines disparate inspirations and takes three seemingly different characters (Nausicaä, Artemis and The Lady Who Loved Insects), ultimately merging them into one engaging protagonist in his film.

While Miyazaki’s Nausicaä isn’t a carbon copy of the one Homer describes, and Miyazaki took many liberties in his creation of Nausicaä, his film is another token representing how Greek mythology continues to be a source of inspiration and a vital asset to the creative minds in the entertainment industry. Because myth is so diverse and widespread, it is possible for Miyazaki to treat myth as a buffet where he can take as much or as little of what he wants. Furthermore, he can combine what he chooses and mix it with his own personal philosophies and Japanese culture, stories and even mythology. In addition, while Naussica isn’t the most prominent character through Homer’s Odyssey, the sheer fact that when “Nausicaä” is typed in Google and Miyazaki’s film appears first, whereas Homer’s Nausicaä is secondary, proves that Miyazaki’s revival of this myth ultimately credits myth’s ability and nature to last and mutate through time.