Director Tarsem Singh merges two different myths together in his 2011 action and adventure film, Immortals. He molds the stories of these myths, the Titanomachy and Theseus, into one myth in order to better suit his film. He takes creative liberties and changes the stories, which differ greatly from Apollodorus’s versions. King Hyperion, the antagonist, is a power-hungry man who seeks the Epirus bow after losing his family to plague. The bow is loosely related to the bow of Hercules. This bow oozes power as Hyperion eventually uses it to free the Titans, who battle the Olympians in what should be known as the Titanomachy 2.0. The timeline for Immortals takes place after the Titanomachy, and the plot revolves around Theseus and his tasks. The Titanomachy, however, repeats itself as the Titans are eventually freed by the insane King Hyperion and battle the Olympians. Singh’s Immortals evokes a multitude of interests. One of these interests includes the presence of gods in the movie when no gods are mentioned in Apollodorus’s version after Theseus’s birth (Poseidon and Aigeus share Theseus as their son). Theseus’s battle with the Minotaur portrays another interest in the differences and artistic interpretation that Singh takes in the events that take place during the myth of the Minotaur. The most important piece of Singh’s piece surrounds Theseus and his relationship with Zeus and the Olympians, one curiously similar to the relationship between Moses and God in Judaism and Christianity, but quite different from Apollodorus’s version of Theseus.

Director Tarsem Singh merges two different myths together in his 2011 action and adventure film, Immortals. He molds the stories of these myths, the Titanomachy and Theseus, into one myth in order to better suit his film. He takes creative liberties and changes the stories, which differ greatly from Apollodorus’s versions. King Hyperion, the antagonist, is a power-hungry man who seeks the Epirus bow after losing his family to plague. The bow is loosely related to the bow of Hercules. This bow oozes power as Hyperion eventually uses it to free the Titans, who battle the Olympians in what should be known as the Titanomachy 2.0. The timeline for Immortals takes place after the Titanomachy, and the plot revolves around Theseus and his tasks. The Titanomachy, however, repeats itself as the Titans are eventually freed by the insane King Hyperion and battle the Olympians. Singh’s Immortals evokes a multitude of interests. One of these interests includes the presence of gods in the movie when no gods are mentioned in Apollodorus’s version after Theseus’s birth (Poseidon and Aigeus share Theseus as their son). Theseus’s battle with the Minotaur portrays another interest in the differences and artistic interpretation that Singh takes in the events that take place during the myth of the Minotaur. The most important piece of Singh’s piece surrounds Theseus and his relationship with Zeus and the Olympians, one curiously similar to the relationship between Moses and God in Judaism and Christianity, but quite different from Apollodorus’s version of Theseus.

In the Titanomachy according to Apollodorus, the gods fight the titans for ten years and

eventually win, shutting them up in Tartarus, guarded by the “Hundred-handers”. The Immortals’ version of the Titanomachy happened a little differently. Tartarus, a pit in the depths of The Underworld in most Greek writings, is a mountain in the Immortals. The Titans are not what you would imagine Titans to look like. They are not huge, monstrous creatures, but humanoid figures, with gray skin and emotionless, red eyes. They are trapped in a sort of cage in Tartarus, held there with stakes placed horizontally through their mouths. There are no “Hundred-handers” to guard them. It is hard to completely replicate the Titanomachy because of the details of the war and the short period of time in a movie, but at least Singh described the Gods-Titans quarrel.

Zeus and Theseus’s relationship in Immortals is very different than the relationship that Theseus has with Zeus in Apollodorus’s version, because there is none. The only presence of gods in Apollodorus’s version is before Theseus’s birth, when Poseidon becomes his half-father. In the rest of Apollodorus’s version of Theseus’s myth no gods are mentioned. So why has Singh so heavily involved someone to hold Theseus’s hand throughout the film? Singh uses Zeus as a father-figure and teacher to steer Theseus on a course for success. The lessons that Theseus learns from Zeus mirrors some of those from God to Moses, as a teacher and guide.

In the film, Zeus encourages Theseus by telling him “I have faith in you Theseus. Prove me right. Lead your people”. Zeus’s guidance of Theseus is similar to God’s encouragement of Moses to carry out God’s command. Although their tasks aren’t similar, Theseus tries to prevent the Titans from escaping “Mount Tartarus” while Moses labors tirelessly to gain the Jews freedom. The way in that they are guided by higher beings is eerily parallel. Both Moses and Theseus lead their respective peoples, Theseus leading the Greeks and Moses the Jews. Theseus and Moses both come from backgrounds that lead them to be out casted, Theseus as a “bastard” child in this movie and Moses as an adopted son. Both of them eventually rise to unmatched power, Moses as a prophet and Theseus an Olympian god. These two heroes stand for good against evil. God chose Moses just as Zeus chose Theseus. A major difference in these two is that Zeus doesn’t want to intervene in human affairs. It ends up being the other Olympian gods Ares, Poseidon, and Athena that help Theseus to his destiny. God in the Old Testament on the other hand, speaks and intervenes directly with Moses, telling him to lead his people out of Egypt and into Israel. The parallelism between Moses and Theseus makes Theseus a hero in Greek mythology, but in monotheism, a prophet. A central theme of both Moses’s story and the main theme in Immortals is faith. Both men have faith, but end up having it differently. Moses always had faith in God. He never doubted his faith. Theseus, on the other hand, had to be shown the supernatural in order to have faith. This is where Immortals gets corny. The journey of faith should be one that is discovered on one’s own, not delivered when an Olympian swoops down and saves you from death on multiple occasions.

Faith plays such a huge role in Immortals, yet is neglected to be mentioned in Apollodorus’s version. Theseus bests all enemies in Apollodorus simply because he is stronger and a better warrior. Singh wanted to appeal to the audience in that faith means everything and when someone lacks faith, he/she also lacks vitality. This is shown when Theseus almost dies of exhaustion when taken slave at the salt mines, only to be saved by his future lover Phaedra. He asks her why a person would rescue a complete stranger. “Only a faithless man would ask such a question” she responds. She then persuades Theseus to bury his mother the way she wanted to be buried, with her rites and faith. When he buries her he finds the Epirus bow, restoring his faith and becoming an unstoppable force. This shows that faith gives you the needs to overcome your enemies.

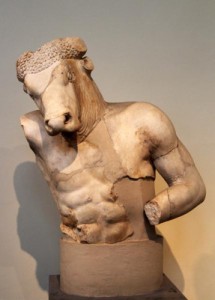

Greek mythology describes the Minotaur as the half-bull, half-man son of Pasiphe and a bull sent by Poseidon. In Immortals the Minotaur doesn’t live in the Labyrinth, as it does in Greek mythology. There is no King Minos, whose closest replacement would be Hyperion. There is, however, the wire-mask man sent by Hyperion to the Labyrinth where Theseus is burying his mother after she is killed. The wire-mask man, known as “the beast” to Hyperion and Immortals, but the Minotaur to all other interpretations, is eventually killed by Theseus The Minotaur in Immortals is a man, but with a wire-mask in the shape of a bull. It is peculiar as to why Singh made the Minotaur as a man instead of a “half-breed” because the movie was already filled with supernatural beings, gods and titans. In the opening credits of the movie, quote from Socrates appears on the screen, saying “All men’s souls are immortal. But the souls of the righteous are immortal and divine.” Animals are at a scarcity in this movie and Singh may have wanted the movie to go off of this quote by keeping the Minotaur a man, saying that his soul was neither divine nor righteous. The movie fails to really grasp the whole “Labyrinth” version. There is no string or ball of yarn that Theseus uses to maneuver the Labyrinth, instead, after killing the “Minotaur” he takes one left and one right and is home free.

Apollodorus’s Theseus is a fantastic myth because there is very little Olympian god involvement. The myth of Theseus is about a man who strains and fights without the help of the gods, eventually leading him to the founding and ruling of Athens. Because Immortals has so much god influence, it dampens the meaning of the Theseus myth, that a hero CAN accomplish many things without the interference/divine help of the gods. Although Immortals was still entertaining and fun to watch, it lacked mythological accuracy.