This blog has quite thoroughly documented Vassar College’s relationship with the Casperkill Watershed, mostly because of Vassar Lake and Sunset Lake which are part of it. But there is a little known part of the college campus that is also part of the watershed: the skating pond. Off the beaten track of campus, the Skating Pond lies in the northeastern section of campus, past Kenyon and before faculty housing and nestled by the Manchester Road entrance by Route 55. Though it has fallen into disuse and hardly looks like a body of water now, it was at one time a third option for Vassar students looking to have some wintery fun.

The skating pond today, covered almost entirely by Sagittaria, an adaptable, hardy plant species. The water in the skating pond is diverted from the Casperkill.

Since its creation, the pond has spent most of its life in disuse. It was proposed by Louis P. Gillepsie, who was the general manager and purchasing agent for the College. In 1923, the College bought 117 acres of land, originally the Wing Farm, which eventually would contain Kenyon and Blodgett Halls, the golf course, Palmer House, faculty housing, and Wimpfheimer Nursery School. Gillepsie’s vision for part of the land was a body of water even larger than Sunset Lake. Then President Henry MacCracken built on the proposal, suggesting that the low-laying land by the “brook,” presumably the Casperkill Creek, be flooded.

Where the Casperkill and the Skating Pond intersect. Water is diverted from the Casperkill here; the metal dam seen replaced the concrete one when it was restored in the 1990’s. It is now rusted and fairly ineffective.

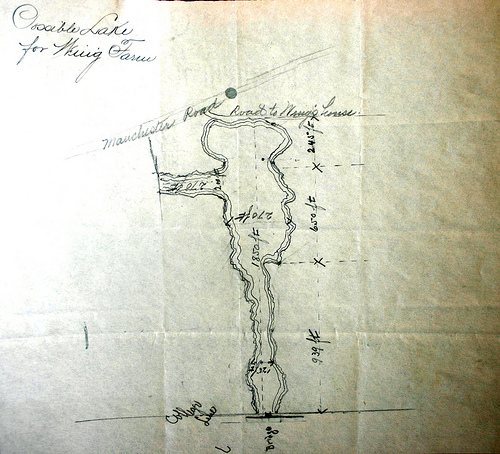

Two years later, Mr. M. Sugar, who worked in the office of the superintendent, created a rough sketch of what the proposed lake would look like. Later, after Kenyon Hall was built (the school’s much needed up-to-date gymnasium), paths were constructed to connect the physical activity areas to Kenyon, such as the golf course, the sports fields, and the skating pond.

M. Sugar’s sketch of the skating pond. He originally envisioned a lake 1,850 feet long from north to south and 270 feet at its widest point. When the skating pond was built, it was about a fifth of the intended size.

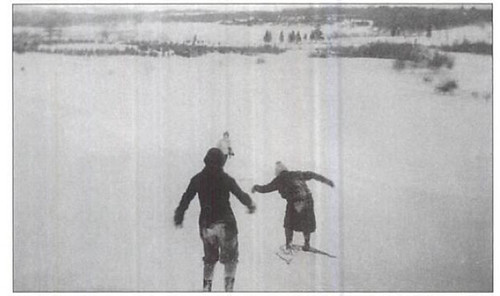

The pond was used for about ten years–Sally and Joslyn Magowan, ’37, a pair of twins who would be associated with professional figure skating, used the pond for practice–before it fell into disuse. It remained in that state for fifty years, until it became part President Frances Daly Fergusson’s revitilization plan for Vassar’s buildings and grounds in the 1990’s. Along with the Skinner boardwalk and the Vassar Lake trail, the skating pond was targeted for reclamation and restoration.

One of the benches installed by Jeff Horst and Buildings and Grounds.

Jeff Horst, the Buildings and Grounds director at the time, along with a four person crew, spent two full weeks pulling out invasive species like honeysuckle and purple loosestrife that had dominated the pond. The also replaced the concrete dam with a metal one, in addition to installing three benches along the pond’s shores. They also restored its original purpose, and created a system in which a red flag would fly if the pond was not frozen enough for skating, and a green flag would fly if it was skate-able. Student, faculty, and the public were all welcome to use the pond, but it never became popular with students, and was mainly used by faculty families. After a few seasons, the pond again fell into disuse.

The skating pond from Manchester Road. No longer regularly tended by Buildings and Grounds, purple loosestrife has returned to the pond.

This post was adapted from the entry “The ‘Skating Pond'” on the Vassar Encyclopedia, found here.

Photographs taken by Tess Dernbach; sketch is from a letter from M. Sugar to President MacCracken, April 24, 1925. (VCSC)

Posted in Casperkill | No Comments »