Featured: Zeiss Microscope and Marcella Grady

Today we take for granted the incredible resources available at Vassar. We have computers on every surface, pianos in every common room, and a constant introduction of new technology. In 1890, the Vassar’s Biology Department had one teacher who every year had to beg for better lighting and adequate equipment. The college had more pianoforte instructors than professors of the sciences. And yet, today our Biology Department has over 100 majors. It all started with one teacher and a microscope.

Up until late 1889, Vassar had the Natural History Department, offering two courses, Zoology and Botany, both taught by professor Sanborn Tenney. In the fall of 1889, the college hired Marcella Grady to teach Biology. In her first report to the college’s president, Dr. James M. Taylor, she reported the donation of a brand new Zeiss microscope, “of the latest and best pattern and high power.” The microscope was the beginning of Vassar’s love affair with the newest, state-of-the-art equipment and scientific approaches. This microscope, which was designed in 1885 and reassessed in 1889, is a product of Micro Optics, a company based out of Fresh Meadows, N.Y. It was of enough importance to be documented in the Annual Biology Department report as well as the College Notes in an October 1890 issue of the Miscellany News. It was the first high-powered microscope the college had received. In her first report to the President in the spring of 1890, Professor Gray outlined the department’s equipment from that year:

“By the kindness of Prof. Dwight, portions of the natural history laboratory have been set apart for biological work. These have been fitted up with work tables, glassware, reagents, a few aquaria, microscopes, dissecting and other instruments including in addition to the twelve Bausch and Bohme microscopes already presented to the college by Mr. Thompson, especially one Zeiss microscope of the latest and best pattern and high power.”

The college still has the microscope today as part of the College’s Historical Artifacts Collections.

In the fall of 1889, the Natural History department changed in curriculum and name, becoming the Biology Department. The following year, only juniors and seniors could take courses in Biology. From today’s perspective only allowing a select number of juniors to enroll in general Biology sounds preposterous. In 1890 however, it was an incredibly radical move for a school. Professor Grady outlined her goals for her biology students in the 1890-1891 school year.

“In this course, two objects have been kept in view: 1) to impart such a knowledge of plants and animals as shall be useful to the students whether they intend to make a special of Biology or work; to give a knowledge of the essential features of vital structures and action; to teach the outlines of classifications and to give the training that can only be acquired by long-continued practical study in the laboratory; 2) to prepare the students both in biological knowledge and in technical methods for the more advanced work of the senior class.”

Students from this time period kept records of what they saw under the microscopes. They stained cells and tissues using the most current techniques and drew intricate pictures of what they saw under the microscope. Within a few years, the department acquired camera lucida devices, which were basically mirrored tubes that enabled the students to essentially trace out what they saw under the scope. The women carefully and painstakingly drew what they saw through the lenses, using fine-tipped fountain pens. Afterwards, the drawings were lightly colored with ink, pink, grey, to highlight the colorful stains they had used to showcase the otherwise transparent cell structures fixed between the glass slides.

This Zeiss microscope was not the college’s last. Grady convinced the school to let her order 12 more in years to come, as her department became more popular and her students needed more equipment. Still, it’s amazing to think a microscope made of brass and finely ground lenses contains this much history and had such a great impact on the science education at the turn of the 20th century.

By: Emily Omrod, VCAP Intern, Class of ’16

VCAP in the Miscellany News

“Artifacts catalogue milestones in Vassar’s rich history”

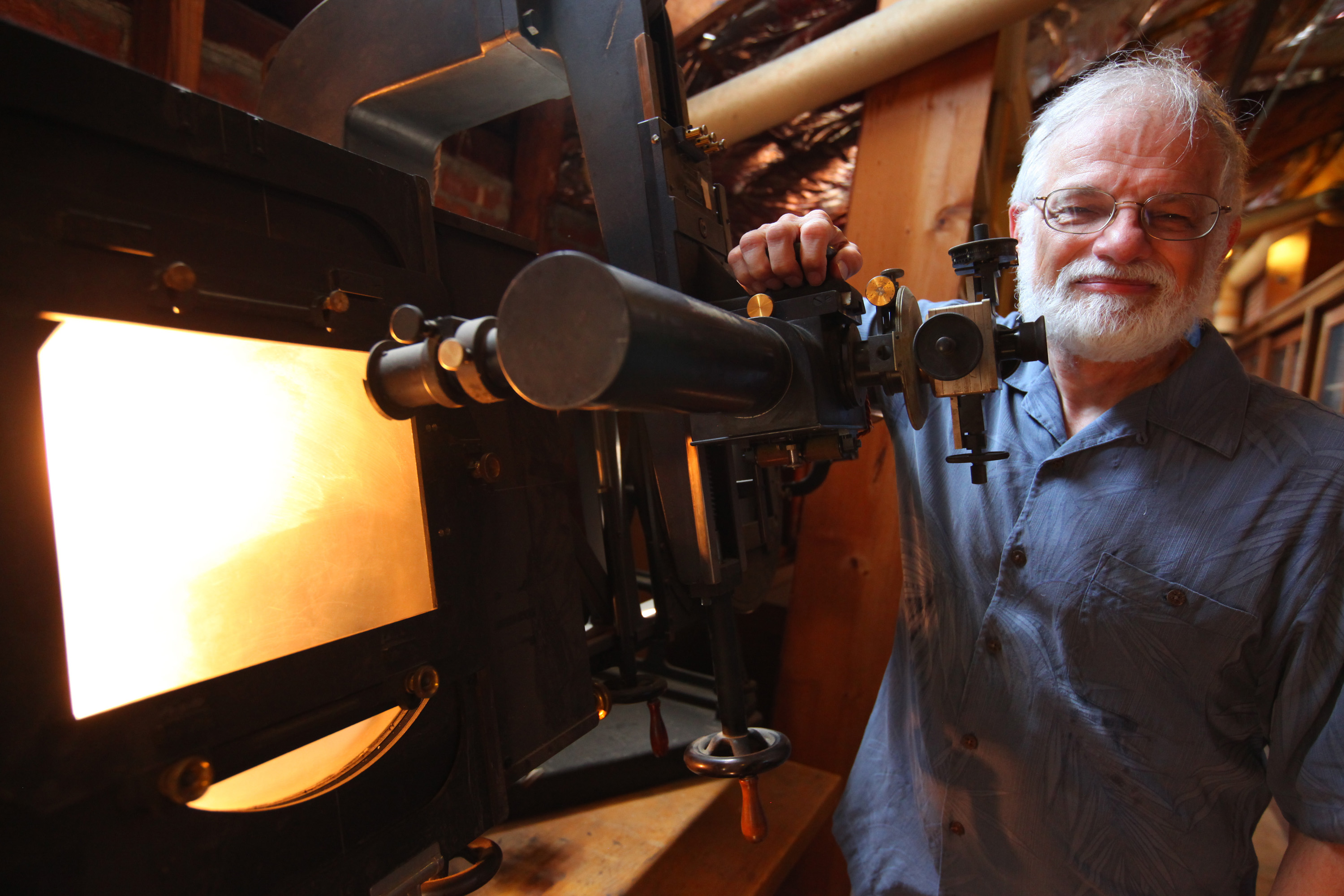

Professor of Astronomy Fred Chromey stands by a piece of historical astronomy equipment from the Vassar College Artifact Project. The project seeks to preserve, research and restore the outdated teaching aids of yesteryear. Photo By: Vassar Artifact Project

Though they have been collecting dust for several years in the buildings scheduled to undergo renovation, Vassar’s educational artifacts will once again see sunlight. Instead of throwing them out, Vassar College faculty and staff, together with students, have decided to celebrate these forgotten relics by saving, researching and restoring them into the teaching collection on campus.

The Vassar College Artifact Project was conceived in 2011 by the College Historian Betty Daniels ’41 and Professor of Biology Kate Susman on their bus ride to New York City to attend a gala marking the College’s 150th anniversary.

According to Laboratory Technician Richard Jones, who is heavily involved with the project, it was conceived to protect and preserve educational artifacts, especially from Sanders and Olmstead. This was due to the renovations scheduled for this summer.

Since then, the project has been joined by dozens of other faculty, former faculty, staff members and students.

The project started in February of this year when two students, Michael Hughes ’14 and Emily Omrod ’16, were recruited as interns to create a website that will document the narratives that go along with the artifacts.

Omrod called it an amazing opportunity to learn more about and be involved with Vassar’s educational history.

“I get to read documents from the founding of Vassar. I love learning about these objects that are an important part of Vassar’s history. It’s fascinating to compare Vassar in the 1890s to now. So much has changed and yet, the passion of the students is still the same,” she said, emphasizing the continuity of the College’s history.

Jones, along with Administrative Assistant of the College Lois Horst have been involved in preserving and displaying many of the College’s historical items, including the Natural History Museum in Ely Hall. Jones wrote in an emailed statement, “[It was] natural that we get involved in the Vassar College Artifacts Project.”

Jones has been heavily involved in cataloging, assessing, cleaning and packing up collections from the attic of Sanders and Olmstead, which have accumulated more than 100 years of equipment that needs to be moved for renovations.

Through this project, numerous educational artifacts from different departments have been restored and preserved, including: an original Morse telegraph saved from Sanders Physics, glass replicas of jellyfish and other organisms crafted in the early 20th century by world-renown glass makers Rudolph and Leopold Blaschka, saved from the renovation of Swift Hall.

One of the important artifacts re-discovered in the attic of Sanders Physics building is the blink comparator, an astronomical instrument. According to Professor of Astronomy Fred Chromey, it is one of the only two still in existence in the United States.

The VCAP website mentions that it is unusual for a small liberal arts college to have such an expensive device: “The larger research universities—Stanford, Harvard, Chicago—all had them at one time, but for a place the size of Vassar, that was remarkable.”

Also included in the collection is an antique brass telescope that had been used by the celebrated astronomer Maria Mitchell, who taught at Vassar from 1865 to 1888.

According to Senior Lecturer of Science, Technology and Society James Challey, a member of the VCAP committee, “All our astronomy equipment is top of the line because that’s one of the things that made the College famous in its early years.”

Another item of interest is the Zeiss Microscope, which was donated to the college in 1889. It was the first high-powered microscope that the College had received.

In the fall of that year, the Natural History department changed its curriculum and name, becoming the Biology Department. As such, these educational artifacts carry with them important stories about the College and its foundation that otherwise might be lost if not for the project.

The participants of the VCAP have mentioned that the creation of its website has been an important step in creating a space for the stories that go along with these artifacts.

Jones said, “The history of many professor-student classroom interactions can be found in these objects, and it opens a fascinating look into the history of Vassar College that would be lost if these items are allowed to disappear, or be thrown out.”

Challey said he was confident that the College would find ways to save science equipment that is worth saving. In fact, he believes it is crucial to Vassar’s relationship to the sciences.

“It’s important that we do this. It will show how Vassar fits into the bigger picture of the development of science, especially physics and astronomy,” he said.

Looking ahead, the committee members have already held preliminary talks with architects for the new science center about finding space to display at least some of the artifacts, bringing some of Vassar’s richest histories to the campus’ future.