The National Policy Act from 1969 was an environmental law that was put in place to advocate for the enhancement of the environment and helped establish the President’s Council on Environmental Quality. The part of this law that affected Native Americans was section 101(b) which made sure the federal agencies had to be aware of the cultural impacts on historic (Native American) sites before they did anything to disrupt them.

The NEPA section 101(b) states:

In order to carry out the policy set forth in this Act, it is the continuing responsibility of the Federal Government to use all practicable means, consist with other essential considerations of national policy, to improve and coordinate Federal plans, functions, programs, and resources to the end that the Nation may

- fulfill the responsibilities of each generation as trustee of the environment for succeeding generations;

- assure for all Americans safe, healthful, productive, and aesthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings;

- attain the widest range of beneficial uses of the environment without degradation, risk to health or safety, or other undesirable and unintended consequences;

- preserve important historic, cultural, and natural aspects of our national heritage, and maintain, wherever possible, an environment which supports diversity, and variety of individual choice;

- achieve a balance between population and resource use which will permit high standards of living and a wide sharing of life’s amenities; and

- enhance the quality of renewable resources and approach the maximum attainable recycling of depletable resources.

(For full NEPA text click here)

This piece of legislation although with good intentions was really more of just a “procedural policy” made to inform the federal agencies of its environmental impacts than to outright stop them. This means that they just have to have fully informed decisions about the impacts that certain public works projects would have. It does not necessarily guarantee the safety for these sites, even if they are acknowledged as significant cultural places.

“Although NEPA does not always produce favorable decisions or champion tribal causes, many tribes are involved with the federal process. Unlike other federal statutes, NEPA is triggered by a broad range of federal actions. Given that NEPA casts such a wide net, it is inevitable that NEPA reviews frequently involve tribal lands and resources. Even though the execution of NEPA leaves much to be desired, its very existence presents tribes with opportunities that might ix NEPA/TEPA Guide for Native American Communities otherwise not exist. It carves one of many needed communication channels in the dynamic and ever-evolving relationship between sovereign tribal governments and agencies of the federal government.” (A Comprehensive Guide For AMERICAN INDIAN and ALASKA NATIVE Communities

Also, with this legislation, the burden of proof to protect these important cultural sights fell again onto Native American tribes. If they didn’t want a highway or some other public works project to demolish a sacred sight for them, they had to provide the evidence that this place was infact an “important historic, cultural, and natural aspects of our national heritage”. While a reasonable request for the tribes to have to provide evidence to support their sacred land claim, the claims weren’t always granted. This makes many Native American tribes wary to disclose important cultural sights to the American government because of all the times they have been burned in the past.

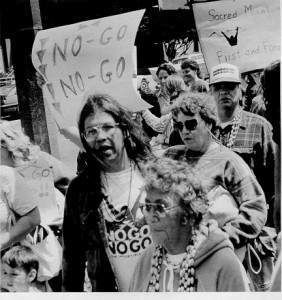

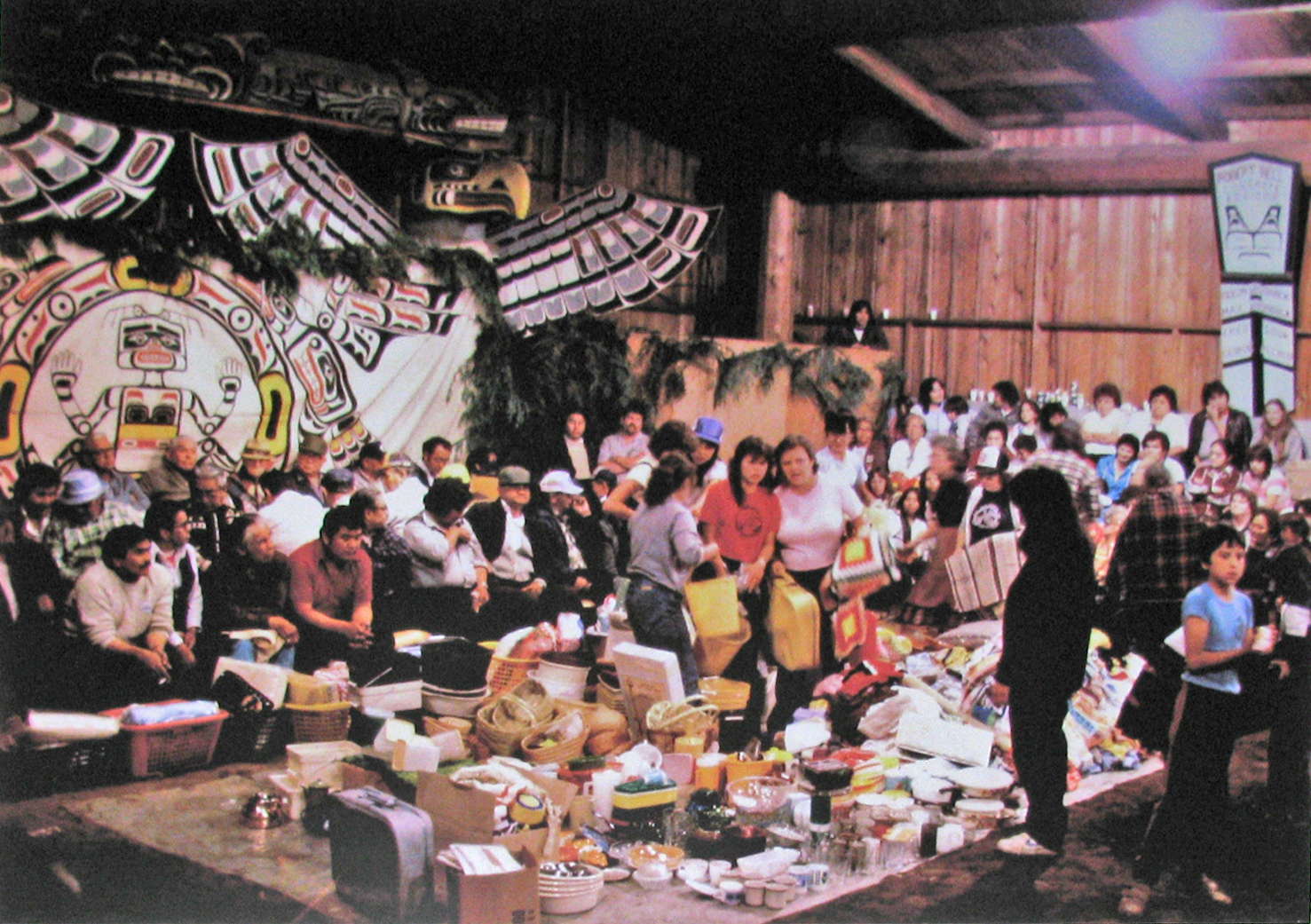

An Idle No More rally to save Indian Heritage School was held May 15, 2013 at the Seattle School District offices. Was not successful.

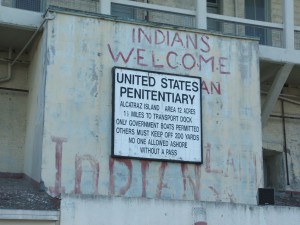

Another problem with this piece of legislation is that it does nothing to help the Native peoples repatriate other important sites which the government had taken from them previously. This law is to simply help preserve their cultural sites, which puts the emphasis on the history of these places instead of focusing on the tribal members still alive today. It reiterates the false theme in America’s legislation of Native Americans that they are dead or going and all we can do to help is to preserve their history in order to remember them. Most American legislation on Native Americans is not about helping and making up to the living members still alive today for all the crimes that have been committed against their people.

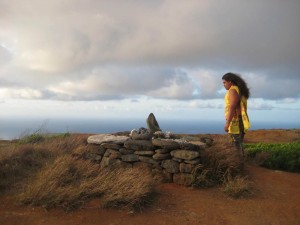

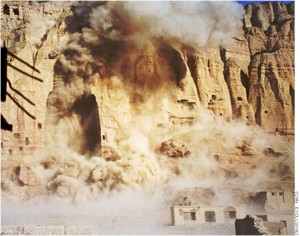

Larkspur, California a burial site over 4,500 years old containing 600 human bodies was annihilated for the construction of a housing complex. This is it after it was paved over

http://pages.vassar.edu/realarchaeology/2014/11/16/rare-indian-burial-ground-demolished/

Further Reading:

http://www.achp.gov/book/case101.html (when NEPA 101(b) was used in a lawsuit)

http://www.tulalip.nsn.us/pdf.docs/Tribal_EA_Handbook.pdf (legislation guide for Tulalip Tribes of Washington: “A Comprehensive Guide For AMERICAN INDIAN and ALASKA NATIVE Communities”)

Sources:

http://www.tulalip.nsn.us/pdf.docs/Tribal_EA_Handbook.pdf

http://energy.gov/sites/prod/files/nepapub/nepa_documents/RedDont/Req-NEPA.pdf

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Environmental_Policy_Act