The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 and the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 have affected the citizenship of Native Americans, the structure of current Native American governments, and the land to which Native nations lay claim. Although in my research I did not find analysis of how these laws directly relate to current debates concerning repatriation, I believe that these laws come to bear on these processes due to their effects on Native American systems of governance and the land that officially belongs to Native peoples.

First, a bit of history concerning these two acts.

The Indian Citizenship Act can be understood as an attempt to assimilate all Native Americans into the U.S. sociopolitical mainstream, and has complicated understandings of the citizenship of Native Americans. This act extended citizenship and the right to vote in U.S. elections to all Native Americans while also stipulating that Native Americans would maintain their tribal membership – in effect, granting all Native Americans dual citizenship (Fine-Dare 64). However, as David E. Wilkins (Lumbee), professor of American Indian Studies explains in his article “Dismembering Natives: The Violence Done by Citizenship Fights,” this dual citizenship is fraught with historical complexities that have helped to create current conflicts concerning tribal governance and citizenship. Wilkins explains that these complexities include a denial of rights of Native Americans as guaranteed by U.S. citizenship by individual states1 and the effects of U.S. v. Nice (1916), which asserts that Native Americans are “simultaneously ‘citizens’ of and ‘subjects” to U.S. law” (Wilkins). Wilkins frames these complexities of legal identity and the specter of complex U.S.-imposed definitions of citizenship as a reason why corrupt or ineffective Native American governments are not being critically engaged by other Native Americans. He argues that Native American leaders who see problems in other Nations are reticent to speak out against corruption because of a historic mistrust of the U.S. government and a fear that critiques of tribal governments will invite the U.S. to infringe upon Native American sovereignty.2

The Indian Reorganization Act (1934) has also shaped the structure of current Native American governments. This act not only ended the policy of Allotment initiated in 1887,3 but also allowed Native Americans to create governments modeled on that of the U.S. This act has been criticized both by Americans concerned by the increased ability of Native Americans to retain land and by Native Americans who find the imposition of Euroamerican systems of governance detrimental to the well-being of their Nations.4 Many Native Americans protested that this rigid governmental system did not reflect and thus denigrated their own traditional forms of governance, and that this imposition created internal tribal divisions between those who supported traditional governance and those who approved of the IRA (Churchill, Ward, Morris 15). Additionally, although this law gave Native Americans the ability to buy back land taken from them by the U.S. government under Allotment, Native Americans were not able to fully reclaim all land lost, and all transfers of land had to be of a “voluntary” nature on the part of the new white owners, instead of mandated by the government.

Both the Indian Citizenship Act and the Indian Reorganization Act have affected current structures of tribal governance, which directly impacts the ability of tribes to successfully go through the process of repatriation. Perhaps repatriation claims made by Native American citizens would not be heard or respected by tribal governments that aren’t representing the will of their constituents. Additionally, there is the potential for friction between U.S. federal structures and policies (like NAGPRA) and tribal governments if the U.S. believes that the specific Native government is corrupt. Additionally, as Native American citizenship becomes murky with the additive effect of multiple laws legislating citizenship, it may become harder to adequately demonstrate lineage or National citizenship that relates a claimant to artifacts or land as required by federal legislation such as NAGPRA. Finally, the inability for Native nations to reclaim the land taken from them illustrates the fact that there exist massive tracts of land that once belonged to Native peoples but are no longer held by them.

Ultimately, exploring these acts sheds light on current complexities of Native American citizenship, structure and function of tribal governments, and what is believed in mainstream U.S. discourses as land that belongs to Native Americans.

Footnotes:

1. For instance, Utah did not recognize Native Americans as U.S. citizens until 1962

2. For extended coverage on the debate surrounding disenrollment, listen to the segment “I Know I Am, But What Are You” from This American Life, episode 491. http://www.thisamericanlife.org/radio-archives/episode/491/tribes?act=1

3. The General Allotment act (1887) divided most Native American reservations into 160-acre zones that were then distributed to male heads of household tribal members. All other land left over after this distribution was automatically bought by the US government at a low price who began selling it to non-Native settlers. The money from these transactions occasionally went back to the government but frequently went instead to the tribe to be distributed among members (Deloria and Lytle 5). Between 1887 and 1934 approximately two thirds of all reservation land in the continental U.S. was seized by the government under allotment (Churchill, Ward, and Glenn T. Morris 14)

4. For a detailed analysis of the history of tribalism and its problematic application as an “authentic” structure of Native American life, see p. 86 of “Retribalization in Urban Indian Communities” in American Indians and the Urban Experience (http://www.amazon.com/American-Indians-Experience-Contemporary-Communities/dp/0742502759)

For further reading/listening:

Below are three excerpts (both audio and transcript) of interviews with a Sioux attorney, a Sioux tribal chairman, and a Sioux tribal leader, who express different opinions on the benefits and detriments of the IRA to the Sioux Nation.

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/76/

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/34

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/33

Bibliography

Churchill, Ward, and Glenn T. Morris. 1992. Key Indian Laws and Cases. In The State of Native America: Genocide, Colonization, and Resistance, 13-21. M. Annette Jaimes, ed. Boston: South End Press.

Deloria, Vine, Jr., and Clifford M. Lytle, 1984. The Nations Within: The Past and Future of American Indian Sovereignty. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Wilkins, David E. May 16, 2014. “Dismembering Natives: The Violence Done by Citizenship Fights” Indian Country Today Media Network, accessed February 10, 2015. http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/05/16/dismembering-natives-violence-done-citizenship-fights.

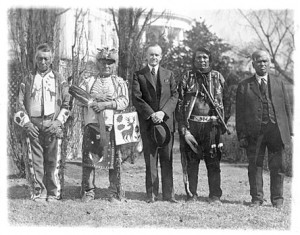

Pictures:

Picture 1: http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0700/frameset_reset.html?http://www.nebraskastudies.org/0700/stories/0701_0146.html

Picture 2: http://www.nlm.nih.gov/nativevoices/timeline/452.html

Picture 3: https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/images/3/32/Americanindiansmapcensusbureau.gif