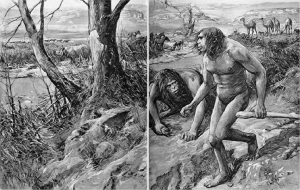

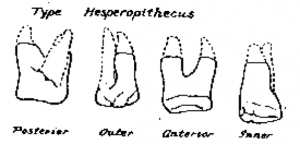

What do the so-called “theories” about ancient aliens, the Lost City of Atlantis, and eBay postings about “rare Native American art pieces” have in common? Each one of these are products of pseudoarchaeology, a counterfeit version of true archeology whose proponents rely on bias, ignoring accurate scientific methodology and evidence to produce unrealistic ideas about the past. Though it is impossible for archeology to be completely free of bias, those who subscribe to pseudoarchaeology are taking it to a whole new level. More often than not, pseudoarchaeological ideas are produced in the face of the inaccurate interpretation of evidence, such as in the case of the Nebraska Man, a famous example of pseudoarchaeology in which the tooth of an extinct species of peccary found at a dig sight in Nebraska was touted as evidence of a “missing link” in human evolution in North America for several years in the 1920s.

Though this particular instance of poor scientific method and pseudoscience may seem more humorous than harmful, the ramifications of this bad science still had adverse effects. Besides hoodwinking a number of professionals, “evidence” of the Nebraska Man was used during the infamous Scopes trial to combat the teaching of evolution in schools. No matter how well intentioned those who endorse pseudoarchaeology may be, the fabrication of a bogus theory based off of scant evidence, as well as using that theory to promote ignorance among the general populace such as in the Scopes trial, is inherently harmful.

As we discussed in class, pseudoarchaeology rears its gruesome head for more instances than just the far-flung, highly publicized bungles like the Nebraska Man. Indeed, this kind of bad science is widely propagated, and even accepted, in everyday life. Misrepresentation of artifacts to fit modern stereotypes of past cultures and peoples, such as selling a broken piece of a common-place object used by Native Americans as an ancient piece of artwork, disenfranchises and creates a racist view of their capabilities.

This is the more sinister side of pseudoarchaeology; bad science aside, it spreads racist sentiments, thereby justifying certain actions that otherwise would not be justifiable. For example, how is it possible that almost 200 years after the Greek government requested it, a large portion of the frieze from the Parthenon, an important piece of Greek cultural heritage which was purchased from the Ottoman Empire in the 1700s by a British archaeologist, has yet to be returned and still resides in the British Museum? How is it possible that stereotypes about African cultures being perpetually less evolved than those of Europe could ever have been propagated when sites such as great Zimbabwe still stand after hundreds and hundreds of years? Pseudoarchaeology will always exist where people are looking for sensationalism or support for their own theories instead of the truth. The best way to combat this is to look to science as a guide and maintain a high level of respect for the people and cultures that we seek to study.

Sources

“Elgin Marbles.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 26 Sept. 2017, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elgin_Marbles.

“Creationist Arguments: Nebraska Man.” Creationist Arguments: Nebraska Man, Jim Foley, 30 Apr. 2003, www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/a_nebraska.html.

Forestier, Amadee. Evolution Hoaxes – Nebraska Man. N.d. ThoughtCo. 30 Mar. 2016. Web. 28 Sept. 2017.

Chrisomalis, Stephen. “What Is Pseudoarcheology?” PseudoArchaeology Research Archive (PARA). N.p., 2007. Web. 28 Sept. 2017.

Sánchez, Juan Pablo. “How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles.” National Geographic. National Geographic Partners, LLC, 28 Mar. 2017. Web. 01 Oct. 2017.

Gregory, William K. “Biographical Memoir of Henry Fairfield Osborn.” (1937): n. pag. National Academy of Sciences. Web. 30 Sept. 2017.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul Bahn. Archaeology Essentials. 3rd ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2015. Print.

Further Readings

- http://pseudoarchaeology.org/index.html

- Check out these links for contrasting views on the status of the Elgin Marbles…

Although their are many postings of rare Native American Art pieces, that are fake or mislabeled. Collecting Native American artifacts is a practice that often is detrimental or legal depending on the artifacts. Although in the United States we have NAGPRA which offers some protection (but its far from perfect), how does international collecting of artifacts help and hinder archaeology?

Artifacts carry a special cultural meaning for the country of their origin, so when an artifact that carries that kind of weight is removed from its homeland without the permission of its people, a line is crossed. Respect for other people and their cultures is crucial to archaeology, as one must attempt to understand an artifact within its cultural context, and not within one’s own. When this respect is violated, archaeology is inherently hindered. However, if the international collecting of artifacts is done with the permission of the country of the artifact’s origins, collaboration and fresh perspectives may lead to new understanding.