History is the study of the past, usually in a narrative sequence of events. History places events in nice neat time periods ignoring the complexities of how the transitions occurred. Archaeology helps provide the understanding of how these changes occurred through examining and analyzing culture. One of the ways this is done is through fieldwork.

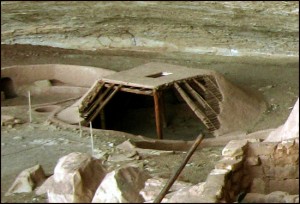

In class we examined the Cultural History of Anasazi; Anasazi is the archaeological term used to describe one of the four prehistoric Puebloan peoples in the region of the American Southwest right above Mesoamerica. In the Cultural History we learned that Anasazi culture dated back as far as 1,500 BC and has been spilt into eight time periods based on their tools, religion, architecture, and agriculture. The first time period is framed from 1,500BC- AD 50, where they used cave campsites for storage but in the next time period from AD50- AD500 they developed pit houses. Pit houses were built partially underground with a mound above the surface and a hole in the roof called a sipapu that symbolized the entrance into the spirit world.

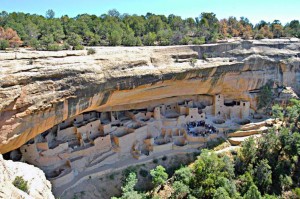

Over time agriculture became more developed which led to communities being formed as well as a spiritual structures called kivas. The communities kept expanding to large pueblos and many kivas until the seventh time period from 1350 AD- 1600AD where the kivas started to become very scarce. Then the last time period from 1600AD- present the Spanish arrive and establish missions.

All of this is a great framework of history of Anasazi but it doesn’t tell us the hows and why. We know from 1350AD- 1600AD the kivas became very scarce but why? What happened to the religion that could have caused that, did the Katchina cult development have any bearing on the disappearance of the kivas? These questions are where archaeology becomes helpful. To explain, Patricia Lambert of Utah State University and Brian Billman and Banks Leonard of Soil Systems excavated a pit house near Cowboy Wash in southwestern Colorado in the late twelfth-century A.D where they found a lot of inconsistency to the cultural history layout. The site was a Pueblo III habitation, during this time period pit house have been long outdated and replaced with large pueblos. They also found that the sipapu had been sealed and the criteria for cannibalism had been met. With this newfound information we can start to make theories as to why these particularities had occurred. Some believe the land was a marginal environment not fit for agriculture which wouldn’t allow this particular area to have time to create large complex housing. The cannibalism could have occurred simply from a lack of food and desperation; however other believe it could have been a spiritual offering since the sipapu had been sealed.

As you can see history gives us a nice framework to work within but archaeology allows us to closely examine and analyze the convolution of these events through culture.

sources:

April Beisaw, Archaeology 100, Class #15

A Case for Cannibalism,” ARCHAEOLOGY, January/February 1994

Amélie A. Walker, Anasazi Cannibalism?, Volume 50 Number 5, September/October 1997

In his book Disaster Archaeology, Richard Gould takes a critical look at the evidence for cannibalism in one Ancestral Puebloan settlement, Cowboy Wash, Colorado. (The term “Anasazi” actually derives from the Navajo name for their neighbors and is seen by many as pejorative.) Researchers at Cowboy Wash excavated three pithouses that date to around 1150 A.D. and found the “disarticulated, defleshed, and apparently cooked remains of seven people of both sexes and different ages on floors and other nonburial contexts.” (Gould 141) Two stone tools, which were of the type often used for butchering animal remains, tested positive for human blood. Some shards of cookery also tested positive for human myoglobin, which is found in skeletal and muscle tissue and is species-specific. Human myoglobin was also found in a human coprolite (fossilized fecal matter) at the site. These results seem to support the conspecific consumption of human flesh (cannibalism) at this site, but does not and cannot imply a widespread cultural practice. This could have been the behavior of a few individuals, of a small group, or only of the people living in this settlement – and it’s important to be sensitive to the historic discrimination against native groups when discussing a topic of this nature. When thinking of cannibalism, many people immediately picture gastronomic cannibalism, instead of the far more likely starvation-induced cannibalism or institutionalized cannibalism (to show respect for the deceased, or assert social power over enemies). We must be very wary of saying that archaeologists have concrete proof of cannibalism, especially since unfounded claims of widespread cannibalism formed the base of many racist and discriminatory academic works in the past.