The interior of Bath Abbey is absolutely crammed with graves, plaques, and monuments of every kind commemorating the many prominent people who over the centuries came to Bath to take the waters and be cured, and died instead. But of course there are many citizens of Bath, who spent their lives here and made contributions of all kinds to the city, buried in the Abbey as well. I have come here in search of the grave of Signor Venanzio Rauzzini, a splendid musician of Old Europe, who came to join the fashionable and Modern society represented by Bath, and brought with him his talent, his energy, and all the kindly connections he had formed over the years, and put them all at the service of his new home. I am an admirer of Signor Rauzzini.

Bath Abbey is not one of the really old churches in England, though it stands on the site of a Norman church. But the Abbey did not begin to rise until 1499, and had not long been finished when King Henry VIII decreed the dissolution of the monasteries, and the new Abbey was stripped of everything valuable, including its windows, and left empty and open to all the elements. Of course eventually the Abbey was restored and by the eighteenth century had become much as it is today: a working church with all the usual services, a place where one can hear lovely music at Matins and Evensong with occasional recitals on the organ, and a boisterous meeting place for all the tourists who swarm to Bath during the summer months. For the Abbey is situated right next door to the famous Pump Room, where then as now you can swallow three glasses a day of curative, sulphurous water, and dine elegantly in a spacious room where a trio quietly plays. On the day of my visit, the yard that joins the Abbey and Pump Room is thronged with spectators watching a man juggle with flaming batons while balancing on a unicycle. Not exactly the atmosphere of hushed reverence one associates with an Abbey churchyard, but very, very Bath.

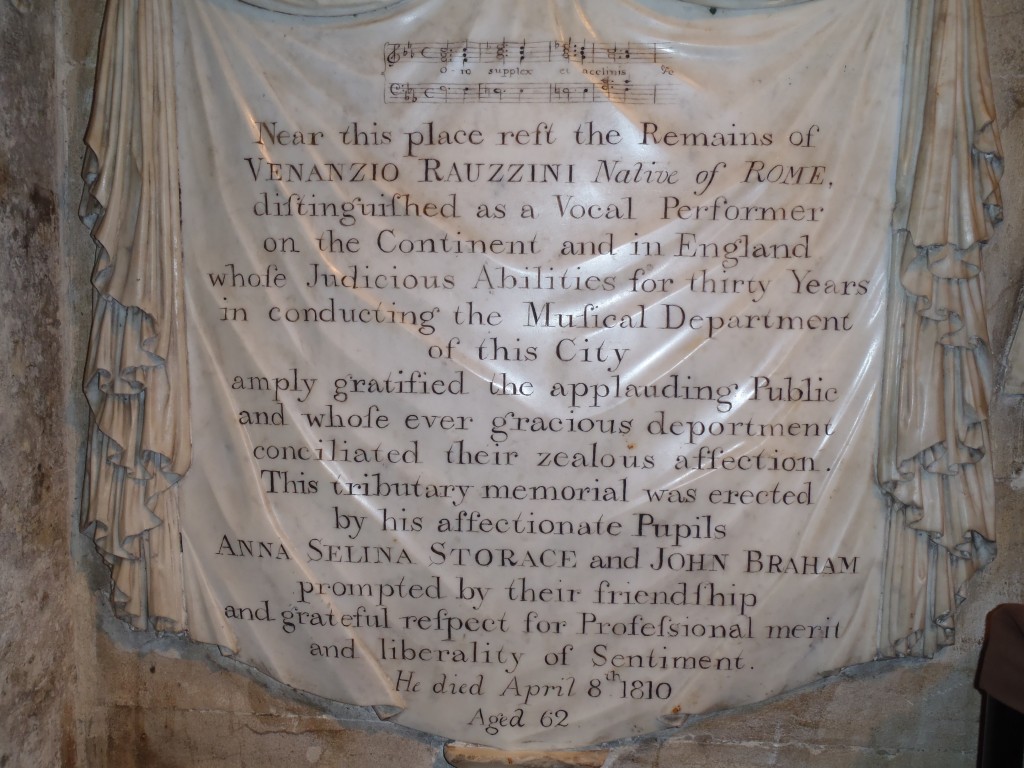

Eventually I make my way around the nave, which is quite a beautiful, very light space with delicate fan vaulting; and all the way at the farthest possible reach from the altar, in a tiny enclosure tucked away in the southwest corner of the nave, I discover Rauzzini’s memorial.

Venanzio Rauzzini was born in 1746, and when I say that he was a musician of Old Europe, I mean that he began his career on a fairly traditional path for an Italian opera singer. He became a castrato at some point in his early youth, and appeared in his first opera before he was twenty. He performed in many opera theatres in Italy, and was in residence at the court theatre in Munich for a time, travelling to Vienna for appearances as well. When Mozart produced his opera Lucio Silla in Milan in December 1772, Rauzzini was one of the performers. Mozart must have thought highly of him, since the following month he wrote a marvelous virtuosic motet, Exultate jubilate, for him. Not long after this Rauzzini went to London and began an association with the King’s Theatre as both singer and composer. But in 1777 Rauzzini moved to Bath, and unlike so many other visitors he decided to stay, settling into a house at 13 Gay Street and eventually purchasing a lovely villa at Perrymead, a village high in the hills to the south of the city. He took part in many concerts and when his friend, the musician and astronomer William Herschel, left Bath in 1782 to concentrate on his scientific studies, Rauzzini succeeded him as Director of Concerts at Bath’s celebrated Assembly Rooms.

Now Rauzzini became a great impresario, arranging hundreds of concerts and bringing many of his famous students – Elizabeth Billington, John Braham, Charles Incledon, Michael Kelly, Madame Mara, Nancy Storace – to perform, often at much reduced fees from what they would earn in London. By all accounts Rauzzini was a generous and congenial colleague, teacher, and friend. John Braham and Nancy Storace, who contributed the plaque in his honor at the Abbey, were among the foremost singers of the time; Storace even forms a link with Rauzzini’s early years, since she too sang for Mozart, as the first Susanna in Marriage of Figaro. One can imagine the conversations they might have had about their experiences with Mozart. In 1794 Europe’s greatest living composer, Joseph Haydn, came to Bath and stayed with Signor Rauzzini at his villa, immortalizing his favorite little pug dog, Turk, in a canon.

Among the residents of Bath during Rauzzini’s era was Jane Austen. For a few years she and her family lived in a house overlooking Sydney Gardens, where we know that she attended outdoor entertainments with fireworks and music. She also attended evening gatherings at the Assembly Rooms, and one of the most potent scenes in her novel Persuasion takes place at a concert in the beautiful concert room there, with Italian love songs in the background. In 1805 Austen moved to 25 Gay Street, and was thus living only a few doors away from Rauzzini. So it’s quite likely that she knew him by sight, highly likely that she heard him perform, and beyond doubt that she knew his music, since a duet from his opera Alina, o sia La Regina di Golconda survives in her family’s music collection, which I’ve been studying at Chawton.

Rauzzini died in his Gay Street house on 8 April 1810, and a notice in the Bath Chronicle read, “In private life few men were more esteemed; none more generally beloved. A polished suavity of manners, mild and cheerful disposition, and a copious fund of general and polite information, rendered him an attractive and agreeable companion . . . in Mr. Rauzzini, this city has sustained a public loss.” At Signor Rauzzini’s grave, I reflect on his life, its times and places, his acquaintance with Mozart, his shared milieu with Austen, the complex patterns formed in his long and happy career at Bath, and feel a loving sense of recognition and appreciation.