OMD were a perfect fit for what I had in mind for DinDisc — they had a serious, artistic side with real depth, as well as a commercial, pop side. That duality was reflected in all the early DinDisc signings, like Martha and the Muffins, and then the Monochrome Set.

– Carol Wilson, head of DinDisc Records

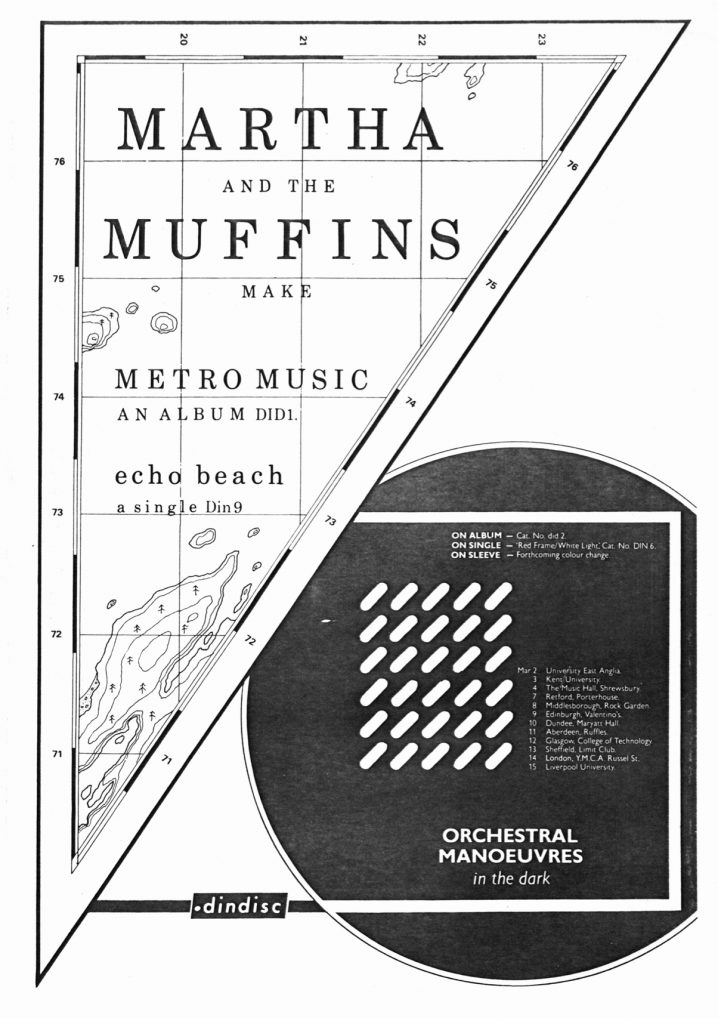

In operation for roughly three years, 1979-82, the London-based record label DinDisc Records — an imprint of the Virgin Records empire — put a slight but valuable spin on the development of new wave music, most significantly via the early albums of OMD. However, it’s difficult to find good historical information about DinDisc, leaving outsiders with a lot of questions. Was DinDisc a genuinely “indie” label? Was its name correctly spelled with two capital letters (“DinDisc”) or just one (“Dindisc”)? Intrigued by such esoterica, fans and archivists often have to resign themselves to browsing the DinDisc catalogue on Wikipedia, finding the bands they’re particularly attached to, and projecting their own knowledge of those musicians’ activities during these few years to this obscure label.

That’s how I arrived at the DinDisc story, through my own archival research and original interviews on the case of Martha and the Muffins. The Toronto band’s commercial ascent and the subsequent careers of its members intersect indelibly with DinDisc Records, the label who signed them to their first recording contract and made possible the worldwide success of “Echo Beach.” Drawing from my research for a book focusing on Martha and the Muffins and the Toronto scene they hailed from, in this essay I provide a historical overview and explore the catalogue of DinDisc Records. I rely heavily on secondary sources I found in libraries and online about the British music industry (Virgin Records in particular) and DinDisc recording artists (most deeply for OMD), supplementing these with my own supplement my own original interviews with Martha and the Muffins, their original producer Mike Howlett, and DinDisc label head Carol Wilson.

In the beginning: Virgin Music and Carol Wilson

The story of DinDisc Records revolves around a pioneering woman of the British music industry, Carol Wilson. While there’s surprisingly little material of historical depth to be found regarding her time presiding over DinDisc, more is known about her prior years inside Richard Branson’s Virgin group as head of its music publishing unit, Virgin Music, in the mid-1970s. I’ve written the story of DinDisc around her chronology, in the hopes of describing its industry contexts and creative relationships with some sociological perspective.

Wilson first connected with Branson indirectly via his mother, Eve Branson, who she met on the beach in Mallorca, where she was vacationing after dropping out of Royal College Music. Upon return to England, Carol “mucked about” in the music business, first as secretary to Nat Joseph at Transatlantic Records. Then in 1974, she applied for the position of marketing director at Virgin Records, which she learned of in a Music Week announcement. Out of 50 applicants, she made the last stage of interviews (as she says in this YouTube clip):

because Richard always went by the face and whether he got on with people rather than what they knew. And then he said, “Well, I can’t give you this job because actually you don’t know anything about marketing, do you?” And I said, “No!” And he said, “Well, we’d like to give you a job. What would you like to do?” And I said, “Well, anything but a secretary.” Because in those days, all of the women were secretaries; there was nothing else.

And he rang me up a few days later and said, “How would you like to run our music publishing company?” So, instead of just saying yes, I actually — it’s fitting, it’s why I fit in at Virgin so well, I already got the bluffing sorted out — I said, “Well, it sounds like a very interesting idea. But I’ll only take it on if you give me my own head in running it and let me run it the way I like to run it.” I didn’t know what a music publishing company was! And he was delighted at that because Richard delegated everything. I mean, he never got involved in detail, or he didn’t know anything at all about music, and he just relied on getting a team around him that would work it all out and achieve everything for him. So that was music to his ears when I said that’s what I wanted to do.

Only in her late twenties, Wilson had entered a key position inside the fledgling Virgin group. As explained in Branson’s autobiography Losing My Virginity, when signing recording artists, he and Virgin Records co-founder/chief music executive Simon Draper pursued three objectives that leaned heavily on the functions of its music publishing unit Virgin Music:

We set out to own copyright for as long as possible. We tried our hardest never to agree to a deal where the copyright reverted to the artist because the only assets a record company has are its copyrights. We also tried to incorporate as much of an artist’s back catalog into our contract, although this was often tied up with other record labels. Beneath all the glamour of dealing with the rock stars, the only value lay in the intellectual copyright of their songs. We would thus offer high initial sums but try to tie the artist in for eight albums…

Right from the start Simon and I tried to position Virgin as an international company, and the second thing we always insisted on was incorporating worldwide rights to the artists’ copyright in our contracts. We would argue that there was less incentive for us to promote them in Britain if they then used their success here to sell well overseas.

One last negotiating point was to ensure that Virgin owned the copyright of the original members of the band as well as the band themselves… We had to ensure that Virgin didn’t sign a band only to be left with an empty shell while the lead guitarist went on to succeed as a solo artist on another label (Branson 2004: 100-101).

Source: Music Business UK, 2018, https://www.musicbusinessworldwide.com/files/2018/12/MBUKIssue5.pdf

As head of Virgin Music, Wilson executed Branson and Draper’s strategy in the years when Virgin Records transitioned from progressive, psychedelic, and krautrock to punk and new wave. Further, she made her own entrepreneurial mark; as she told me, “I took the company into signing outside artists instead of simply the Virgin roster. Some of those artistes I introduced to Virgin, like the Human League and Magazine.” DinDisc record producer Mike Howlett elaborated on Wilson’s innovation within the Virgin group:

Carol turned out to be a lot smarter than you might think. She learned about publishing very quickly, and she realized that publishing was creative, that you sign people independent of a record deal. So, she then says to Richard, “I’d like to start signing people. You know, it’s just a whole other thing.” And he goes, “Well, okay, but you’ve got maximum three grand budget to sign anyone.”

She wanted to sign the Stranglers. Their management came to her and said, “Look, we’ve got an album coming out on EMI,” their first album. They hadn’t had any hits really, either, so it was kind of this unknown thing. “We’ve been offered four grand to sign with April, but we really love Virgin. We love the vibe here and we love the vibe as a whole label. We’d rather sign with Virgin if you can match the offer; we’ll go with you.” Carol goes to Richard and says, “Can you match this?” And he said, “Nope, three grand. Sorry, that’s it, I can’t.” The album comes out and for the next year it’s in the top five and Richard goes [in sheepish tone], “Hmm, yeah, well, okay, maybe it’s more than just a dumb blonde who can manage the accounts,” and gives her that [budget].

A few words about Mike Howlett, a key character in the DinDisc story. An Australian emigré, Howlett had played bass since 1973 with Virgin Records artists Gong, an Anglo-French progressive rock act with distinctively trippy vibes. In late 1975 he started dating Wilson and moved in with her in London when he was forced out of the unstable band in May 1976, during the fractious reformulation led by drummer Pierre Moerloen and endorsed by Simon Draper. Seeking a new role in music, Howlett looked into putting together his own recording studio set-up. Wilson encouraged this pursuit and proposed how he could make it happen. He recalls her advice: “Look, you’ve got capital invested in that band. You’ve spent some years of your life building it up from nothing to this, so you have some vested interest in it. Go and tell Richard you want some money for choosing the other version.” Howlett did just that, using Branson’s money to begin procuring his own recording technology.

Next: “Wilson’s dowry”: Sting and Strontium 90.

DINDISC OFFICE DIRECTORY:

1. in the beginning: Virgin Music and Carol Wilson

2. “Wilson’s dowry”: Sting and Strontium 90

3. organising DinDisc

4. DIN 1, DIN 2, DIN 3: the Revillos, OMD, Peter Saville, Duggie Campbell

5. “a bunch of Canadians from the colonies”: Martha and the Muffins, Martha Ladly, Nash the Slash

6. the Monochrome Set, Dedringer, Modern Eon, Hot Gossip

7. the end of DinDisc