Welcome to the first of a series of “lab sessions” this semester in conjunction with the Musical Urbanism seminar.

Tonight we’re screening Hype!, a 1996 documentary that’s currently out of print. This means the version you’re watching was torrented by your professors. Although as we heard it’s also available on YouTube, I promised our students two bonuses if they attended this screening. The first bonus is you get to see it on a big screen, if at low resolution, and at high volume as this music deserves.

The second bonus, if that’s what we want to call it, is you get this very autobiographic introduction to the film. My name is Leonard Nevarez. I was never a participant in Seattle’s grunge scene, but I do count myself a survivor of the grunge generation.

This is me in the fall of 1987, a DJ at the UCLA radio station. Here, my friend Darren Harris and I are interviewing the legendary Los Angeles group Redd Kross with my friend Darren Harris…

[…and here is that band Redd Kross, at the time promoting what is their greatest album, Neurotica.

I got to interview a handful of other groups at KLA: Social Distortion, Primus, a psychobilly group from Orange County called the Swamp Zombies, and in the fall of 1989 Nirvana. This was the pre-Dave Grohl band with early drummer Chad Channing. Nirvana was promoting their first album Bleach; they on their first west coast tour, supporting the Sub Pop group Tad; and they showed up tired and stinky from their van to this station that their label directed them to.

I remember three things from that interview. First, Kurt Cobain asked if we could play something from blues originator Robert Johnson. We went into the music library and dug out a dusty soundtrack album and played it on the air. A few seconds in, Kurt looked at me with a serious frown: “This isn’t Robert Johnson.” It turns out it was a record to a made-for-TV biopic from the 70s, performed by contemporary musicians. Sorry, Kurt.

Second, when the interview was over, the band put me and another DJ friend on the list for the show at Raji’s. In my gratitude, I offered the band one thing that a college student and underground music fan could offer: “You need any pot for the road tonight?” The band looked at each other, and after an uncomfortable pause Krist Novoselic replied: “Naah, but Tad might want some.”

Third, leaving for the show that night, I discovered that my truck had been stolen from its spot on Veteran Avenue in Westwood. So I didn’t get to see Nirvana that night, and never saw them until their last performance in L.A. at the Forum.

There are no pictures of this interview, which I think is telling. DJs at the station liked Nirvana’s first album, but it wasn’t particularly distinguished; it didn’t sound like the future of rock and roll to anyone.

That’s because Nirvana’s record and Sub Pop bands in general arrived in a period where there was already a wealth of similar music. Just in the period when I went to college, we had a wealth of loud, abrasive groups to choose from: Husker Du, Big Black, the Butthole Surfers, Sonic Youth, Dinosaur Jr, Scratch Acid, , the Wipers the Flaming Lips, the Pixies, Los Angeles groups like the Red Aunts, Clawhammer, and on and on.

Nirvana certainly captured the angry despair of Reagan-era youth, but then in their own way so did Janes Addiction, or thrash bands like Metallica, Megadeth, SLAYER. (And yes, some of us listened to those metal groups and crossed the border separating metal heshers from college radio.) The innovation of Sub Pop groups like Mudhoney, Soundgarden, Green River and eventually Nirvana seemed at this time an incremental one, not a great leap.

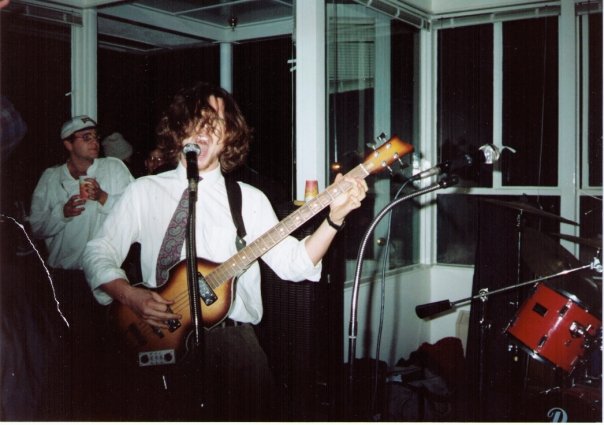

This is a picture of me in the fall of 1991, with my band Phlegmwad. We only played one gig, at this Coop at UCLA. Our concept was to play an ear-splitting, chaotic style of grindcore metal through our admittedly incompetent hands. Following the example of the Jesus and Mary Chain, our set was only 15 minutes long, maybe four songs, then we were done. We were great, if I may say so myself.

This is the rest of the band, Brett on drums and Kevin on guitar. Kevin and some other friends can be seen in Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit” video, quite visible in the front bleachers before the set erupts into a mosh pit. I say this not to show off but to note that this iconic grunge video was filmed in Los Angeles. That was where Nirvana’s major label Geffen was based, but also where the band had a very supportive fanbase by the time they were signed.

One other thing to note about this gig: it was the first time I heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit” in a collective, party setting. The song had come out a month before, and back then new music took awhile to build up a buzz. I knew it was good, but it wasn’t until I saw this crowd, a mix of freaks, stoners, and bohemians — all very jaded when it comes to underground music — just rock out as one, like I had never seen anyone do before outside of a concert, to the famous bridge of the song. You know how it goes…

That’s when I realized that we had crossed the rubicon. Nirvana alone didn’t do it; we all did. And music never was the same for us, as all the groups we liked suddenly got major label deals; almost all of them got dropped once record companies realized they weren’t “the next Nirvana,” and then the prefab Nirvanas started appearing: Stone Temple Pilots, Bush.

This documentary was filmed at a time when Sub Pop and Seattle were just beginning to get some distance from the grunge explosion — an event, centered around Nirvana’s ascent, that no one anticipated. The film betrays an anxiety around what the label and the city that everyone associated with grunge would do next. Sub Pop would have to figure out its next act, which would come in the new millenium with a roster of national artists doing something different than grunge: the Shins, Fleet Foxes, Beach House, Shabazz Palace, and so on.

My conclusion here is to question what is “Seattle” about grunge. That music belonged to us all, although we never called it that, and then grunge quickly became a label synonymous with a city that had never really crossed many people’s cultural radar before. How did that happen? Was Seattle a ‘real’ scene? Or do cities provide symbols that make more dispersed music, geographically speaking, digestible and marketable for outsiders?

1 comment

Rob Cardenaz says:

May 27, 2015

Hey what about the gig at Kevin’s batchelor party, doesn’t count? I think it was only 4 songs too! Oh and I always loved that McCartney bass! ps I just got tickets for Beach House at The Fonda today…