Part three of my response to the question, which performers made the most unexpected left turns with their careers? For the ground rules of eligibility, see the first post; for the big picture of why this is relevant to musical urbanism, click here.

30. U2

Regardless how you feel about the band’s golden age that reaches its denouement The Joshua Tree, let’s face it: by the late 1980s U2 had become insufferable. Has anyone listened to (or — shudder — actually watched) Rattle and Hum lately? If so, were you actually around in those days to see the band gloat in the ‘authenticity’ conferred by B.B. King or a gospel choir? It seems even Bono couldn’t stand himself, as the group’s ego trip with American culture had become a quicksand from which they might never escape.

So U2 went European, so to speak, taking their trusted producers Brian Eno and Daniel Lanois to Berlin’s Hansa Studios (where Eno had left his mark some 12 years ago recording Bowie’s “Heroes”). They got lost in the crowd of the post-unification city, as much as U2 can possibly do that, had some of the most divisive fights of their career, and embraced the city’s cynicism, as symbolized by Bono’s wraparound “MacPhisto” sunglasses. Achtung Baby sounded like an alt-rock record again, while the following Zooropa even flirted with house rhythms courtesy of Howie B and, in the remix and overwrought stage show, Paul Oakenfeld. Does anyone actually listen to Zooropa anymore? (I confess, I’m a teeny bit partial to Oakenfeld’s remix of “Lemon.) Does anyone even remember Pop, the record that followed? It doesn’t matter: U2 had thrown off the straightjacket of their 80s sound and their earnest persona, and established their relevance to music audiences for another generation or two. Possibly several Third World countries are grateful for this.

29. Kraftwerk

“Pioneers” doesn’t even come close to describing German group Kraftwerk’s relationship to electronic music; “gods” might really be more appropriate, given how mindblowing and influential their music has been to audiences and musicians around the world since their 1974 album Autobahn. So seminal, so ur- is their role in electronic music to this day that Kraftwerk seem to stand apart from any other musical movement, or indeed (thanks to their robot avatars) other mere mortals, at least until 1981’s Man-Machine, when electronic musicians began to catch up. Rarely are Kraftwerk associated with the so-called krautrock era of German groups from the late 1960s and 70s — Can, Faust, Tangerine Dream, Neu!, Amon Düül II et al. — whose freeform freak-out music for the head(s) and body went criminally underappreciated until a good decade or two later. By contrast, everyone has always known about Kraftwerk, right?

In fact Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider did come from the “kosmische musik” world — specifically from the same Dusseldorf scene that also yielded Neu! Recordings by the early Kraftwerk include Neu! founders Klaus Dinger and Michael Rother as well as many musicians who moved on before Kraftwerk cemented its final line-up in 1975. Most shocking in this early era is the appearance of non-electronic instruments; while their use is inspired by avant styles that would give rise to Kraftwerk’s more familiar sound, this music sounds radically different and shows little of the group’s later flair with melody. Kudos to Hütter and crew for finding their way to the world’s benefit, but too bad they’ve been so eager to bury any memory of Kraftwerk’s beginnings.

28. Roxy Music

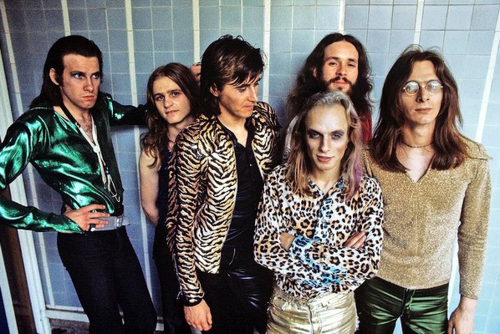

Hooboy, gonna try to restrain myself from overdoing Roxy Music’s praise… Needless to say, by their second album (1973’s For Your Pleasure) Roxy Music had already made a definitive imprint upon British pop music. Brian Eno left that year, and Bryan Ferry began releasing solo albums of covers while fronting Roxy Music for three more albums. Three more fantastic albums (whoa, gotta restrain myself) that honed a distinctly suave, romantic style of rock while gradually fading out their sci-fi/postmodern aesthetic. Then in 1976 they announced a hiatus to pursue more solo work, thereby largely missing out on the punk explosion that took some cue from Roxy’s early creative liberties but which also directed vitriole at its elders. (Poor David Bowie wasn’t so lucky.)

At first, the Roxy that came back for 1979’s Manifesto didn’t seem so different from the lounge lizards seen on the back cover of 1975’s Siren, but over time it became clear that a line had been crossed. For one, Ferry now called all the shots, going so far as to add new musicians to the band (like Paul Carrack, Andy Newmark and Chris Spedding) without ever making clear what this meant for the other founding members. For another, the irony and humor that characterized early Roxy was gone, as Ferry pursued glossy, often danceable soundscapes to back his rather simple romantic sentiments. This transformation divided Roxy fans; some stopped listening, while others followed their cue and even made similar sonic/sartorial upgrades (here’s looking at you, Ultravox and Japan). Indeed, the entire “new romantic” movement owes a great debt to Roxy Mark II. The proof of the pudding is 1982’s Avalon, one of all-time great baby-making records, but a far cry from the days of leopard skin prints and platform shoes.

27. Isaac Hayes

Isaac Haye’s self-reinvention tracked the two eras of Stax Records, the Memphis record label synonymous with southern R&B and soul music. In the mid-1960s he found his way to Stax Records via the Mar-Keys, one of the instrumental groups that held second spot to the label’s house band, Booker T & the MGs. With David Porter, Hayes wrote some of soul music’s greatest hits, particularly for Sam & Dave; one can hardly imagine how the Blues Brothers might sound without this body of work.

As “Soul Man” (to name-check just one of these hits) assumed more militant connotations in the long hot summers of late 60s America, Stax Record changed leadership and moved operations from Memphis to Los Angeles. Hayes used this opportunity to begin recording his own music, leading to 1969’s Hot Buttered Soul, a milestone in soul music. By 1971, he recorded the music for blaxploitation film Shaft and was rewarded with a Grammy for Best Soundtrack. Seemingly unable to make a misstep, Hayes adopted the persona of “Black Moses” (the title of his next album) and became an icon of black America.

26. Everything But The Girl

I’ve said it before: I’m a sucker for the VH1 Behind the Music narrative, of which the career reinvention is a familiar trope. But ultimately I don’t need juicy gossip to sustain interest in this topic; artistic vindication will do when all is said and done. In this light, one of my favorite examples is the Hull, England duo Everything But The Girl. In the early 80s they plyed a tasteful kind of coffeeshop jazz that was of a piece with the London jazz/soul/espresso revival being stoked by magazines like The Face and luminaries like Paul Weller. They did this really well for ten years, thanks to their writing skills and Tracey Thorn’s rich, melancholy alto, albeit never with enough spark to really excite anyone beyond a lonely bedsit.

The turnaround came with 1994’s Amplified Heart — specifically, the remix they commissioned for “Missing,” for which American house DJ Todd Terry created a perfect balance of vocal soul and thumping four-on-the-floor. He claims Thorn and partner Ben Watt were reluctant to release this dramatic remix, but its commercial success coincided with their immersion into British clubland that yielded Thorn’s guest vocal on Massive Attack’s “Protection” and then two fantastic albums. In part, 1996’s Walking Wounded and 1999’s Temperamental succeed because ETBG are generous in crediting the role of their contributors (e.g., drum’n’bass innovators Spring Heel Jack and Photek, house duo Deep Dish), thereby avoiding the appropriation pitfall. More importantly, their melancholy music now had the sonic drama and sense of musical innovation they previously lacked. This period raised Thorn and Watt’s profile considerably; she went on to release three delightful solo albums (including a Christmas record!), he became a creditable house DJ and oversaw the Buzzin’ Fly dance label, and both went on to write acclaimed memoirs.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCkOlvZQiDs

25. Beastie Boys

So much water has gone under the bridge with Adam Yauch’s passing that, for the most part, the Beastie Boys been given a pass for the unfortunate doo-rag get-up they used to wear at the very beginning of their hip hop phase. So let us now remember how they came to hip hop: as a hardcore band looking for new thrills once the CBGBs matinee was getting a little old. They were a quartet back then, without Ad-Rock (Adam Horovitz) and with female drummer Kate Schellenbach (later of Luscious Jackson). That this evidently progressive origins gave rise to a hip hop career that started with a whiff of blackface really says two things. First, that was the early 80s, my friend. Second, it’s hard to think of an earlier first encounter between white artists and non-white art that came off any better. I think many would agree the Beasties properly atoned for this act of cultural appropriation (and, for that matter, the misogyny heard on their early recordings as well).

The only thing to add is that this encounter had a geographic context. The punk-rock Beasties were middle-class upper-west side kids who became obsessed with the music they heard from the Bronx and Brooklyn. And who wouldn’t be? It’s a New York story that will go on until condominiums push the city’s poor and working class beyond the boroughs.

24. Metallica

If you think Metallica’s self-reinvention came when they cut their hair, then YOU DON’T KNOW YOUR METALLICA. I’m talking about 1991’s black album, the one that shifted a billion units, paid for a lifetime of band therapy sessions, and brought the golden era of thrash metal to an effective end. Surely there had to be better ways to turn Jason Newsted’s bass in the mix than this continually disappointing fusion of ass-kicking guitar tone with plodding power ballads?

I suppose no one can blame the band for recognizing when a good thing was about to end. But after the progressive directions of 1987’s $5.98 EP and 1988’s …And Justice For All, I had hoped their sound might evolve into some glorious stew of brutal rhythmic primitivism and a more streamlined comopositional style. In other words, I hoped it would sound more like their cover of Killing Joke’s “The Wait.”

23. Johnny Cash

In the wake of Garth Brooks-mania, the Man in Black couldn’t even get arrested in Nashville, no matter how untouchable his country music bona fides were. He found an unlikely ally in rock/rap producer Rick Rubin, who had just dropped the “Def” from his Def American label and was looking to record a suitably dignified artist. Rubin’s admiration of Cash’s music was sincere, and he proposed a vision that was “more Cash” than anything Johnny had recorded in decades: a bare-bones album of one acoustic guitar and that bass voice, recorded at Cash’s Tennessee cabin. 1994’s album American Recordings was greeted with critical acclaim and hipster embrace; Nashville came around sometime before Cash and Rubin recorded their fourth and final album. By the time he died in 2003, Cash’s legacy in popular music had been fully restored to its proper place.

One can only imagine that Cash had to be seriously prodded to record songs by Danzig, Depeche Mode, Soundgarded or Nine Inch Nails. So this career reinvention may very well be attributable to Rick Rubin, whose work with Cash cemented his status as one of the great music producers of the modern rock and pop era. Traditionalists may argue the Cash-Rubin albums are better understood as a revival, but the willfulness, even contrivance needed to make Cash ‘sound like himself’ is seen in the context of Rubin’s similar efforts with other artists. Among others, Neil Diamond recorded a unjustly-overlooked pair of records with Rubin, using pretty much the same format, that sound nothing like anything in his catalogue but of course are ‘essential’ Neil Diamond.

22. Ministry

Give Al Jourgenson some credit: the guy has so many monkeys on his back, that the beginnings of his band Ministry as a poncey new wave unit are hardly the thing he’s most ashamed about. But it’s true — their first record, 1983’s With Sympathy, is more likely to threaten listeners with the strains of Kajagoogoo than the polymorphous perversity and drug-induced dissolution evoked in later recordings. Perhaps only Ministry’s initial lack of commercial impact persuaded Jourgenson to keep the name, by which time his sound and aesthetic had changed considerably through his involvement with Jim Nash’s Wax Trax! Records label in Chicago.

Several years passed before Jourgenson relaunched Ministry. Most notably, in the intervening period he recorded as the Revolting Cocks with Belgian musicians Luc Van Acker and Richard 23. Ministry’s jackhammer rhythms and oh-so-SCARY vocals surfacing on the next record, 1986’s Twitch, but their sound really coalesced on the following one, The Land of Rape and Honey. The addition of long-haired guitarist Mike Scaccia from Texas speed metal band Rigor Mortis might not exactly be how Jourgenson discovered the joys of 160 BPM riffing, but a better symbol for Ministry’s winning, innovative sound you couldn’t ask for.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fNgnK0-kdfk

21. Aerosmith

Not all career reinventions are worth celebrating. Aerosmith were already front-runners in the annals of 1970s American hard rock when drugs and backbiting drove Steven Tyler and Joe Perry apart during the recording of 1979’s Night in the Ruts. Tyler and whoever else wanted to stick around soldiered on for a couple more records, while Perry launched the inevitable Joe Perry Project, but the magic was clearly gone. What brought them back together? It could have been the rise of hair metal, whereby a hundred vocalists on Sunset Strip stages tied bandanas to their mike stands without every paying Tyler royalties. It could have been the fact that Aerosmith’s fortunes had gone “up their noses,” as Tyler has often admitted. Or it could have been that their appearance in Run-DMC’s “Walk This Way” video papered things over, leading the self-proclaimed Toxic Twins to recognize there was still more mojo to be massaged.

Whatever the reason, 1987 saw the return of a sober Aerosmith proper on Permanent Vacation, which featured the passable “Dude (Looks Like a Lady),” and record-buyers bit. The following record, 1989’s Pump, ruined a perfectly good Aerosmith track “Love In An Elevator” with an irritating 80s-metal chorus (“WHOA YEAH”), but now critics were gushing with admiration for the pop-rock ballad “Jamie’s Got a Gun.” No one apparently saw where all of this was going, so Aerosmith have ever since refused to cede the stage. With the assistance of hired-gun writers, they’ve churned out tacky ballads like “Crying,” “Crazy,” “Amazing” and all those other ones that Adam Sandler skewered so well.

NEXT:

20-11