This summer I begin in earnest a new research project on the Canadian new wave group Martha and the Muffins. I’ve blogged about them extensively already, focusing on the mixed-gender approach and geographical sensibilities that inform their work. The book I intend to write will incorporate these into a new focus: the career of a Toronto band, as understood through Toronto’s musical history, its urban history and geography, and broader social/cultural contexts. It will balance popular and academic concerns, giving music fans the definitive history of Canada’s greatest new wave band while illustrating a scholarly model of creativity and career in place — the latter a recurring theme in this blog.

This book project began with a proposal last spring for a title in the 33 1/3 series of little books dedicated to significant albums in pop. The proposal was rejected, perhaps unsurprisingly since the album I wanted to write about — This is the Ice Age (1981), Martha and the Muffins’ breakthrough third album — was among the more obscure titles in the 410 proposals received for that round. Although it would have been a blast to write a 33 1/3 book, in hindsight it’s better that my proposal was rejected for two reasons: the whole arc of Martha and the Muffins’ career makes a more appropriate object for the kind of analysis I have in mind, and an academic Canadian press is better suited to marketing this book.

I’ll be using this blog to document my research process (including a trip out to Toronto next year) and writing up various essays that may end up in the final book. Or may not, as this project promises a deep dive into the history and music scene of Toronto, North America’s 5th largest city-region (after New York, Mexico City, Los Angeles and Chicago) and in many ways an archetype of polycentric, multicultural urban restructuring. I especially invite comments and correspondence along the way if you have thoughts or leads about the band or their city.

As a teaser for what’s in store this project, here’s the 2,000-word introduction to the title I proposed for the 33 1/3 series.

*******************************

I like to imagine a listener’s first encounter with This is the Ice Age this way:

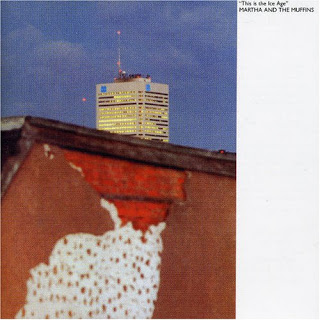

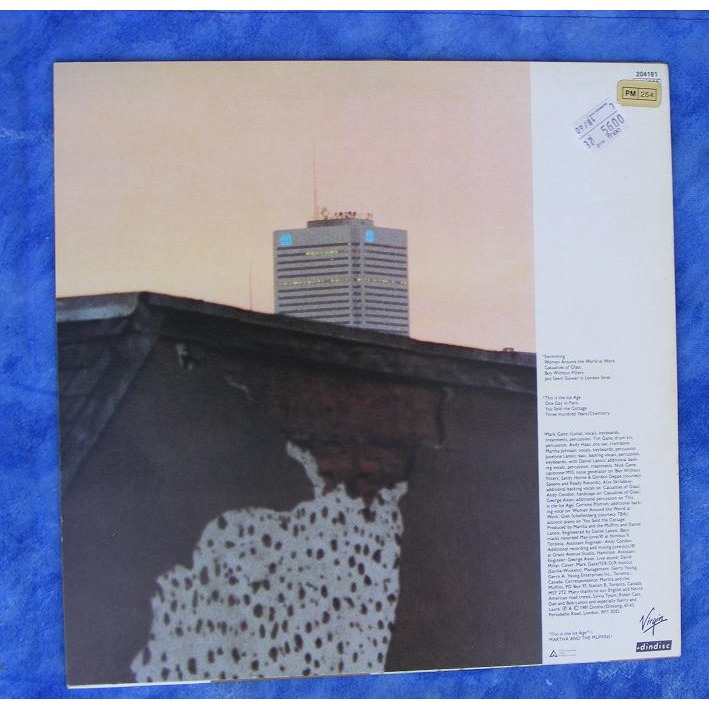

You pick up the album from the stack lying against the bookshelf. A used shirt, a discarded receipt, a fleck of cigarette ash lie strewn along your path to the record player. You take the disc out, put it on the turntable and reach for the stylus. The sleeve distracts you, its minimalist scheme of composition and color palette conveying a inexplicable order that contrasts with all-too-explicable disorder of your room, your life. On the front cover, a foregrounded corner of a distressed building frames the top of the Bank of Montreal tower, in Toronto’s central business district, set against a dusky azure sky, its serenity interrupted by an intrusive white border. The back cover repeats this image against the soft amber of a dawn sky, with fewer building lights on. Flip the sleeve back and forth, back and forth: the image transmits a visual code that you struggle to decipher, its import underscored by the tiny font and startling, business-ledger white of the border. Pay attention to the fine print.

You drop the needle on the spinning record. The gentle rumble of stylus on groove, of a piece with the cover’s mood, is jarred by the sounds of urban traffic, breaking glass, a staccato loop of blaring carhorn. Having rattled your nerves, these sounds fade into a weedy keyboard arpeggio that calls forth a syncopated groove of bass and drum. Now motion envelopes you, a simple minor key two-chord (I-VII) sequence laying the foundation for subtle, insistent rhythm. A man’s baritone croons, holding emotional assessments in check as he describes a strange urban vignette:

Another fight on the street below,

They’ve got things to prove.

Shouting threats and sending out a counterglow.

All they do is walk, talk, knit socks, wind clocks and crawl on their bellies like a reptile.

“I have no idea at all/I have no idea at all.” The arrangement hints at a reggae downstroke, a steppers riddim. “I have no idea at all/I hear a sound.” An arch guitar figure repeats for eight bars before the track breaks down to bass and drum, a flickering tone barely discernible in the background. Pulled out of a normal sense of song-time, you’re immersed in a womblike medium of liquid motion. Then the voice reappears, shattering your idyll:

We talk of parks and simple places,

Sense the thickness of the air.

Highly strung like nervous guitars

My fingers make waves in you.

If you had a passing familiarity to “Echo Beach,” the signature hit of Martha and the Muffins, then you might reasonably wonder, Who is this guy singing? Where are the Marthas? The two female voices whose shared name gave the band its title are absent, as is the saxophone, the new wave backbeat, and clever chord changes that the band’s previous recordings. Instead, “Swimming” presents rhythmic tension, modal composition, sonic depth — new elements for Martha and the Muffins, assembled here confidently. “We’re afraid to call it love/Let’s call it swimming,” guitarist Mark Gane intones, soon joined by two women’s voices, those of keyboardist/vocalist Martha Johnson and bassist Jocelyne Lanois. They repeat his final refrain as a vocal round, that staggered vocal arrangement exemplified by the schoolyard song “Row Row Row Your Boat.” Only here, lyrics and mood invite you off the rowboat into a state of aquatic suspension — the sirens beckoning Odysseus into the deep blue.

“Swimming” and the tracks that follow have a curious effect on the listener, impressing themselves upon the subconscious yet quickly receding from conscious memory. Sewing together contrasts of kinetic rhythms and musical stillness, of emotional estrangement and the reverie of nostalgia, This is the Ice Age, Martha and the Muffins’ third album, has long beckoned its audience back to the unfinished business that begins with their initial listen. This enduring mystery is a measure of its artistic achievement, but it may also explain why the album goes so often overlooked by many of the group’s fans, and why it remains unknown to so many others. This is the Ice Age (hereafter TITIA) presents the listener with a challenging listen — not the sonic trauma of, say, a Throbbing Gristle record, but the riddle of a 50-word zen koan. In 1981, the year when postpunk became new pop and new wave embraced electro-pop, audiences had more obvious thrills and easy amusements to draw their attention away.

Yet TITIA is of a piece with the aesthetic shifts in this formative period of alternative music. One album earlier, Martha and the Muffins were still trafficking in many elements of classic new wave: the revival of the large combo format rooted in American R&B and garage rock, and of 60s girl-group vocal styles; the incorporation of keyboards and saxophone that drew upon 1970s British influences, from early Roxy Music to pub rock; the compositional possibilities revealed by Captain Beefheart’s deconstructed blues and pursued by Ohio groups like Devo, Pere Ubu and Tin Huey; and the ringing guitars of Big Star and other power-pop touchstones. These hallmarks occasionally surface in TITIA, albeit too infrequently for listeners and a record label accustomed to “Echo Beach.”

Instead, Martha and the Muffins’ third album points in two new directions. First, TITIA pursues careful, textured arrangements of danceable rock. Melodic instruments are played percussively, while percussion fills the harmonic palette — methods associated with New York groups like Talking Heads and the Feelies as well as British post-punk groups like A Certain Ratio and Section 25. Second, TITIA embraces a contrasting, solipsistic mood far away from the dancefloor. It offers subdued melancholy on a wavelength similar to moody electronic acts like Orchestral Manouevres in the Dark and postpunk impressionists Durutti Column, while its handful of Satie-like études look back to Brian Eno’s ambient works and ahead to the British pastoralism of Virginia Astley. In 1981, all of this might simply have been called “art rock” — not an entirely inappropriate designation, given the parallel left-turns into new wave exhibited at this time by progressive units and musicians like King Crimson and Slapp Happy. Looking ahead, the sparse soundscapes and intimate meditations on modern life created by Julia Holter, to name just one contemporary musician, are anticipated by this record.

For listeners seeking a music for retreat and contemplation, TITIA has many charms, but charisma generally isn’t one of them. Johnson and Gane’s voices are by turns unassuming and ungainly. Their audible commitment to the music evokes the fine artist’s delight in project conception and problem-solving more than the traditional musician’s virtuosic abandon. Their vocals convey a feeling of holding back, a tone of chill announced by the title.

The estrangement and alienation that pervade TITIA reflect the album’s objectives and the dispositions of the band’s principals, but also the conditions in which the album was produced. After “Echo Beach” delivered a surprise transatlantic hit (reaching #5 in the U.K. charts), Martha and the Muffins quickly left the Canadian circuit to promote two albums, both released in 1980: Metro Music and Trance and Dance. Extensive touring in North America and Europe rushed the recording of the second album, to few people’s satisfaction. Differences over how to pull out of their sophomore slump led to internal discord, unhelpful assertions from the label, and second-guessing among their Canadian cohort. The group retreated to Toronto, leaving a key member (second keyboardist/vocalist Martha Ladly) behind in England.

If this sounds like the set-up for a rock’n’roll bildungsroman, with maybe a pivotal plot turn based on a dramatic showdown with label executives, the facts are both more mundane and more interesting. In 1981, Martha Johnson and Mark Gane were in or near their 30s, and newly resolved to turn the informal collective of their art-school days (epitomized by the band’s irreverant name) into an autonomous, sustainable livelihood. After four years playing together, Johnson and Gane had also become a romantic couple, which reinforced their singular vision for the group. They shrank the line-up, taking on a new bassist and new management. Fortuitously, the bassist suggested a new producer: her brother Daniel Lanois, then an unknown figure with a recording studio in the Toronto outpost of Hamilton, Ontario.

Their pursuit of a more experimental approach and their commitment to Daniel would damage their relationship with the label, who declined to promote the album with its previous enthusiasm and dropped the band after TITIA. The experience caused a loss of nerve for Johnson and Gane, who renamed the group the less silly (and less memorable) “M+M” by the next album. The consequences of this decision would become evident after their 1984 U.S. breakthrough hit “Black Stations/White Stations,” when the band had deprived their commercial momentum of any market awareness of their “Echo Beach” legacy.

TITIA marked a creative rebirth for Martha and the Muffins not despite its trials, but because of them. Recorded by a band emerging out of a period of doubt and transition, it avoids the pitfalls of self-pity and indulgence with its distinct register of emotional detachment. Whether this was artistic strategy or psychological coping, it’s hard to say. Music writers like Theodore Cateforis (in his 2011 book Are We Not New Wave?) view the nervous affect and ironic styles as generic to new wave, but Gane and Johnson, by now the band’s primary songwriters, use their detachment productively as a foil to address broader contexts of alienation and loss. The emotional distances between people, the loss of carefree youth, the shedding of friendships: TITIA articulates such universal experiences into resonant yet unfamiliar forms.

Among these novel forms, the album’s chief themes include estrangement within place (as illustrated on “Swimming”) and from place. Put it this way: if the sound of the original Martha and the Muffins lineup could be said to evoke the late 1970s Toronto scene that they came from, then in contrast to the first two albums, TITIA isn’t a very ‘Toronto album.’ However, in its perspectives on life and experience, and in the musical vocabularies and methods it develops, TITIA is very much an album from Toronto.

As an urban sociologist, my project is to trace human activities and their social organization across the circuits of metropolitan space. The nature of this spatial relationship for the collective enterprise of art is well understood by now. As titles of academic works like Art Worlds, The Warhol Economy and Neobohemia suggest, the gathering of creative individuals in cities generates social relationships, creative opportunities, artistic innovations, and economic undertakings that transcend participants’ individual motives and behavior. Institutions and businesses arise to support and/or exploit creativity and its performance/exhibition; local styles and artistic ways of life develop; and the attentions of critical/commercial gatekeepers, both within and outside the city, put certain artists and their milieus ‘on the map,’ which sets in motion further iterations of bohemian immigration and artistic churn. The Toronto music scene of the late 1970s and early 80s demonstrates these venerable dynamics of art scenes, notwithstanding music historians’ tendency to overlook the city’s punk/new wave era for the commercially successful period before (exemplified by Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, the Guess Who, Rush) and after (Cowboy Junkies, Barenaked Ladies). In this way, the backstory of TITIA provides a useful foundation for examining general foundations of musical and artistic creativity in cities.

A more complex question is the relevance of urban circuits to the experience and meaningfulness of particular artists’ lives. The connection between “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (the title of Georg Simmel’s 1903 essay) is an intriguing one, but scholars are cautious about drawing bold causal arrows from the urban to the individual. People’s lives show the influence of many forces of our socially and geographically mobile world, organized by capitalist exchange, bureaucratic institutions, global media, and the evolving nation-state, not to mention enduring inequalities of race, class, and gender. This complexity suggests it may be at best an amusing distraction to give undue consideration to “who’s your city” (to quote a recent title by creative-class theorist Richard Florida). However, if we pull back from the determinism of a crudely causal approach toward biography, if we reverse the direction of analysis, there’s much of theoretical and historic value to be gained by asking: What do individual biographies reveal about the city? Or, for the specific purposes of this book: What do the creative careers in Martha and the Muffins reveal about the changing nature of Canada’s first city?

Adding an extra twist to this question is the fact that the band’s principals have, in so many ways, been asking it themselves in their own work. A careful glance at their song titles, album titles, visual graphics, and lyrics makes clear that geography and place are recurring motifs in Martha and the Muffins’ body of work. As I’ll show in this book, a spatial sensitivity is evident even in the compositional methods and studio techniques of their recordings. (If that sounds far-fetched, consider that a couple of Muffins have had a hand in landscape architecture over the years.) In this way, TITIA provides a cipher to understand creative lives in place — the origin and arc of a musical group whose ambitions and pursuits evolved in the context of, and as response to, the metropolis they emerged from.

The urban story that TITIA tells isn’t exactly the happy one of self-actualization offered by creative-city cheerleaders. It narrates, not always reliably, the experiences of youthful alienation from stifling suburbia; contestation over the sounds and terms of an authentically ‘Toronto’ music and scene; and mourning for the loss of cherished places and pasttimes to metropolitan development and sprawl. That these frames aren’t always consistent with one another attests to how the dialectic of estrangement from and attachment to place captured by Martha and the Muffins’ music has unfolded over the course of an indeterminate, open-ended biography. Thus, with this book, I invite readers not only to engage a great, unjustly overlooked album, but also to consider how musical creation embodies and reflects the spatial trajectories of creatives lives.

4 comments

Eric Vincent says:

Jul 4, 2014

I’m looking forward to this very much. I am also glad you are not doing this as part of the 33 1/3 series, since so many of those were a disappointing and superficial read for me.

The rejection of your proposal proves to me what I have felt since I was a teen in Montreal in the early 80s: MatM was a personal favorite and it always felt like no one else really appreciated them enough. I don’t know if you want to address this, but I’ve always felt Canada seemed to suffer from an inferiority complex, especially when it came to music. Often, musicians didn’t get much traction or consideration in Canada UNTIL they started getting airplay or consideration from across the border. And even then, there would often be the dreaded addendum at the end of the compliment: “They’re pretty good… for a Canadian band”. I heard this so often, about bands, authors, TV shows, etc… Luckily, in the context of the early 80s and the 2nd “British Invasion” of New Wave music, it felt like a lot of Canadian bands , instead of having to sound like American bands (like the garage rock tinge of the first 2 MatM albums), could create a sound closer to what was invading the airwaves from England: the sound of machines awash in reverb. Artists like The Spoons, The Parachute Club, Blue Peter, Dalbello (Toronto), Strange Advance, The Payolas (Vancouver), Men Without Hats and Rational Youth (Montreal) could “pass” with such British imports as Naked Eyes, Eurythmics, The The, etc…

It will be interesting to get your take on what importance a “pre-U2″ Daniel Lanois, who produced 3 of their albums (don’t forget Danseparc), and who also helped tailor the sound of The Parachute Club as producer of their first album.

I don’t know if you’ve ever seen the 7” single of “Women Around the World at Work” [http://www.discogs.com/viewimages?release=186201], but it also contains a 3×3 grid of pictures of the Bank of Montreal building from the same vantage point at different times of the day, tying in beautifully with the album. We shouldn’t forget the smart and elegant design elements Mark Gane brought to the MatM releases . As a graphic designer, I still find the artwork for TITIA, Danseparc and Mystery Walk fresh and exciting.

Anyway, I wish you the best of luck and can’t wait to read it!

E.

Craig McTaggart says:

Mar 6, 2018

Is your book any further forward ? Would be very interested in a full bio on this great band and the Greater Canadian music scene from which they came . Regards Craig McTaggart Herts UK

Leonard Nevarez says:

Mar 6, 2018

Alas, no, the project moves forward slowly on an academic’s schedule. Most recently I’ve been conducting interviews with Martha Ladly. Look for a book no sooner than late 2019.

Wili Vorticez says:

Oct 26, 2020

This album was a crucial influence on me plying bass and my band’s take on how to be original at the new~No wave sounds. Your taking it seriously is what we did and we got paid to play our own songs starting at 17 years old, partially with Martha & the Muffins 3 albums with J. & D. Lanois influence. My freinds picked up from me even the phrase “that’s so Iceafe” referring to anything that evokes the haunted ghosts of technology and our souls as Burroughs said in the post Hiroshima agr we sre lucky to still have a soul! M + M was the thinking persons postpunk band, and was 1 of 1st bands to make gender not a “thing” way before me too. . .In so many ways they were in fact brillinat from 1981 to 1983 th most important group, period.