I had a brief but interesting Twitter conversation yesterday triggered by Maura Johnston’s link to a New York Times article about how J&R Music World, a venerable downtown NYC retailer of music, hardware and technology, is abandoning its CD sales.

already happened to fans of all music across US… MT @nytimes NY classical fans running out of places to buy CDs http://t.co/QosTSeTCoM

— maura johnston (@maura) January 19, 2014

have said many times that gutting of the retail landscape is a huge culprit as far as music sales’ decline, esp in non urban areas — maura johnston (@maura) January 19, 2014

@maura @MusicalUrbanism I’d argue that wealth inequality/40 years of stagnant wages are the real reasons for the decline in music sales.

— Disco Nihilist (@disconihilist) January 20, 2014

@disconihilist @MusicalUrbanism @maura probably relevant but ppl are paying $175 cable/internet bills & 400$ phones.

— AMP (@all_ages) January 20, 2014

@all_ages @disconihilist @maura retail restructuring & shifting consumerism amid flat income: hard to dismiss any of these structural trends

— Musical Urbanism (@MusicalUrbanism) January 20, 2014

@MusicalUrbanism @disconihilist @maura yes, and it’s all happening in a context of ideologically-driven devaluation of creative labor.

— AMP (@all_ages) January 20, 2014

I’m not just being polite in declining to dismiss any of these points. The causal forces invoked here are broad and multifaceted, and a serious testing of these distinct factors for their comparative significance is beyond the scope of what I know how to do in a quick-and-dirty blog post. But what I can do is give some chronology to these four factors and think through the possible context-cause-and-effect relationships between them.

So here’s an attempt at such a narrative, focused specifically on the U.S setting (which may nonetheless shed light on other nations and regions). Needless to say, I’m making no claims about which factors exert comparatively more influence. No doubt there may be more precise indicators to choose, better data to use, and relevant studies that could put this in sharper perspective. My goal here is simply to extend the discussion and invite your responses and rebuttals.

WAGE STAGNATION/INCREASING INEQUALITY

There’s a lot of consensus on when these dual trends begins: sometime in the mid-1970s, as deindustrialization takes policy shape via neoliberal Reaganomics. Lots of sources for this, including the widely-cited 2007 paper by economists Emmanuel Saez & Thomas Pikkety that formed the centerpiece of an award-winning 2010 article in Slate.

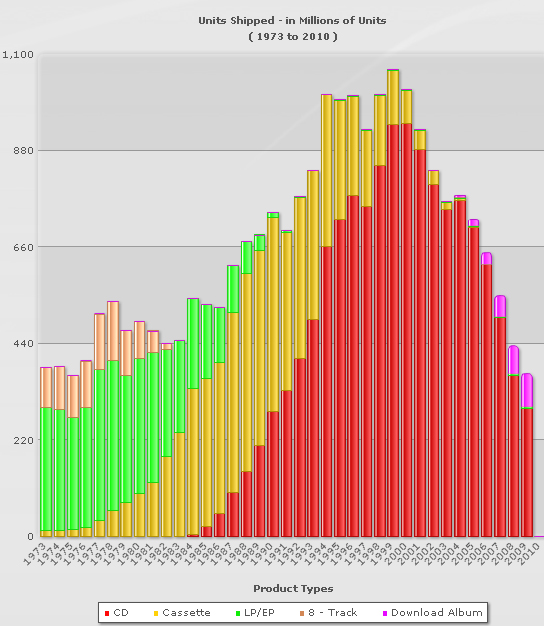

The dual trends of wage stagnation and increasing inequality are gradual, of course. Like the proverbial frog in boiling water, it takes some years for them to start altering people’s daily economic behavior. This is important because of course “the end of the music industry as we know it” didn’t really become obvious for another couple of decades, as illustrated for instance in overall music sales.

I wonder if the timing of wage stagnation and the demographics beneath its early emergence might be relevant. Gen X was still in its youth when neoliberalism began, and the Baby Boom had just moved full speed into its career- and wealth-building years. And we know from the contemporary case that increasing inequality takes many forms, including generational divides in which older cohorts compound their wealth and career success while younger cohorts eke out an unsteady start on the job market (see Jacob Hacker’s 2010 The Great Risk Shift). All of this suggests that a generation well trained in the patronizing of brick-and-mortar music stores and the consumption of albums were disproportionately supporting music retail in the first two decades of U.S. wage stagnation and increasing inequality. Call this the Jann Wenner model of music consumption.

BTW, this is one of the reasons why I’m fascinated with the Kidz Bop franchise, since it was conceived and introduced around the time that the Baby Boom’s kids were coming of consumer age — a shrewd marketing decision in a time of imminent retail instability.

SHIFTS IN URBAN RETAIL

The demise of the brick-and-mortar music store can be contextualized in retail shifts outside the music industry. As sociologist Gary Gereffi and others have recorded, the department store — that emblem of the America consumer mass market, whether in urban downtowns or suburban malls — has been under seige since the 1980s. In its place have grown two retail sectors at opposite ends of the consumer spectrum: the specialty store (name-brand boutiques, niche retail etc.) at the high end and large-volume discount chains at the other. (You can map the growth of Walmart, the ultimate big-box “category killer,” here.) This polarization of retail can arguably be understood as a consequence of general inequality, as most consumers adjusted to getting less bang for their buck.

Music-store chains both old and new would also have to adapt to the destabilizing polarization of retail sectors that. By 1996, Best Buy and Wal-Mart sold 154 million CD — a solid one-fourth of all CD sales that year. That these big-box stores could influence the kinds of music which consumers could find was illustrated by Wal-Mart’s refusal to stock Nirvana’s 1993 In Utero release (see Steve Knopper’s 2010 Appetite for Self-Destruction).

Meanwhile, in 1990, the so-called sanitization of Times Square got underway, thereby opening up a new retail cutting edge in urban entertainment districts. At first concentrated in major cities, this retail form slowly diffused across metropolitan areas, luring shoppers with the “riskless risk” of urban pedestrianism and a mix of specialized retail outlets that ostensibly couldn’t be found in your average mall. Music stores might be one such specialized retail type, but this was more likely a Virgin Megastore rather than a Sam Goody’s. Anecdote: I recall in 1999 visiting a Hear Music store in a small but dazzling storefront on Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade. It offered shoppers headphone listening and a new “lifestyle design” in music selection — two features that, in their own way, would remain prominent after Starbucks Coffee bought Hear Music’s parent company and began selling CDs alongside coffee.

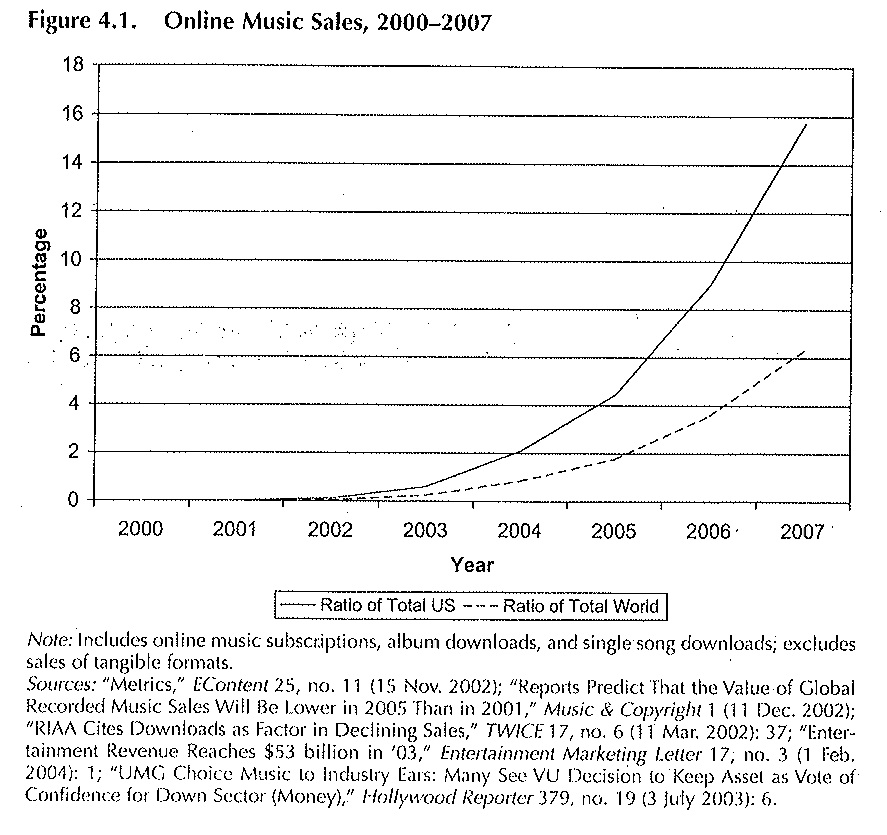

Amazon.com went online in 1995. Starbucks bought Hear Music in 1999 (and sold it in 2008). iTunes was launched in 2003. By 2007, digital music had outpaced CD sales amidst declining music sales overall. These portended the decline of urban music retail as we know it, with Tower Records going bankrupt in 2006, all US Virgin Megastores closing in 2009, Borders Books going bankrupt in 2011, and so on.

DECLINES IN CONSUMER MUSIC SPENDING

To such structural supply-side changes, shifts on the consumer demand-side also play a role. Consumers may be spending less money on music because they have less to spend overall, but alternatives for their discretionary income should also taken into account. Although Baby Boomers may be dispose of their smaller sums on music and movies, the generations after them seem to have taken especially to video games. The consequences are only recently evident as aging Boomers wind down their music and movie consumption. In 2005, video game sales outpaced movie ticket revenues; in 2007, they outpaced music sales.

Personal entertainment devices have also siphoned consumer dollars. As critics of streaming music services have pointed out, while artists and labels see less and less revenue, hardware manufacturers and internet companies have prospered, Apple being a double case in point. The first generation iPhone was released in January 2007, but it wasn’t until the end of the following year that iPhone sales took off. These devices aren’t cheap, and their sales avoid the dreaded saturation effect thanks to Apple’s strategic upgrading of smartphone hardware and operating system. Of course, ring-tone music has been one of the few bright spots in the music industry.

Such big episodic sums aside, your average media-consuming household now pays hundreds of dollars in monthly fees to their media/bandwith providers: mobile phone companies, cable companies, internet providers (increasingly a service of cable companies). As @all_ages pointed out, t’s extremely easy for a household to pay $300 a month to stay wired. In a context of stagnant wages, that too is money taken away from expenditures on music and other media content — the bread and butter of the music store. But importantly, streaming music companies didn’t create this landscape.

DEVALUATION OF CREATIVE LABOR

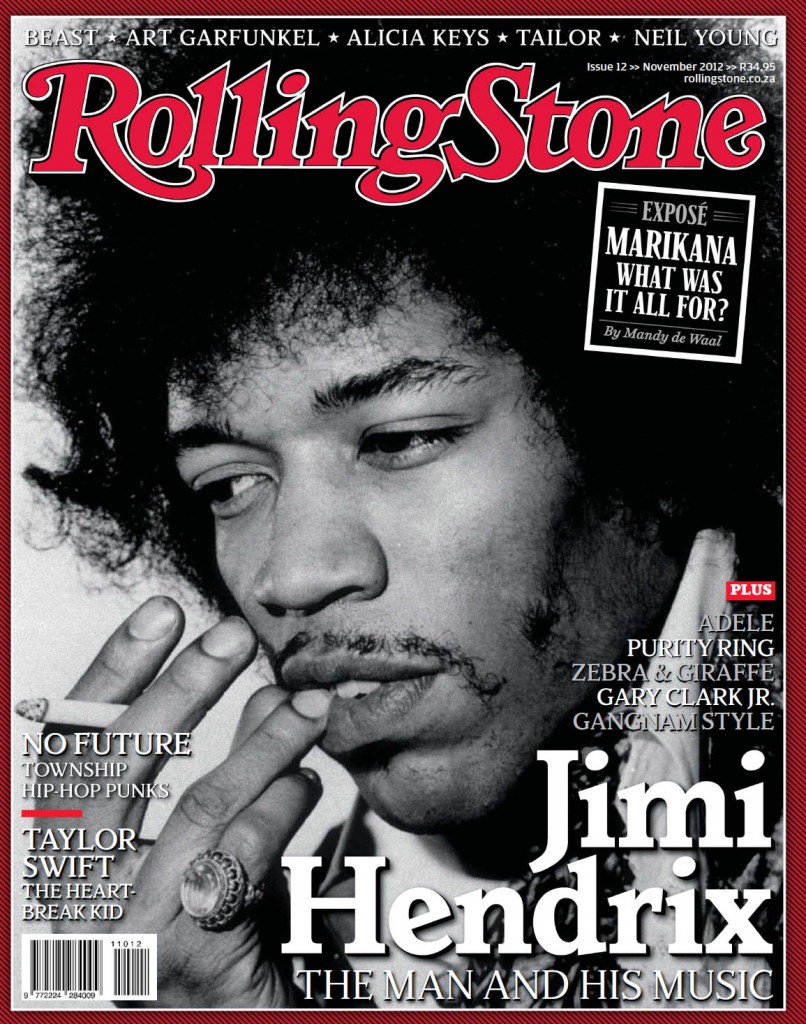

These changes have made the livelihoods of so many recording musicians quite precarious, but that trend has its own history. How much of it can be chalked up to the systematic devaluation of musicians’ creative labor? Possibly the charismatic “cult of the recording artist,” those icons given regular cover space on Rolling Stone, has been taking its lumps since at the 1981 launch of MTV, when musicians suddenly had to be photogenic as well. Maybe a more significant MTV milestone is the 1992 introduction of “The Real World,” which began the steady displacement of music videos by original feature programming that literally put music in the background. Kids today might well wonder why MTV ever stood for “music television.”

Musicians often lament the demise of “artist development” in the recorded music industry — a longer-term orientation by record labels that effectively subsidized the livelihoods of younger artists if the latter needed a few albums to find their commercial voice, so to speak. The end of this heyday is often marked by the late 1990s, when the labels abandoned real music for teen-pop, novelty “electronica” artists, and other singles-based recordings. I find something dubious about this claim perhaps, with its implicit and arguably racialized celebration of the “rock band” ideal. (It’s funny: Brittany Spears, Justin Timberlake, and Christina Aguilera are doing just fine these days.) Maybe we should look further back to the early 80s introduction of the compact disc, when record labels happily gave up on the future to exploit the past, in the form of older catalog reissued on CD for purchase by Boomers and other older listeners.

But in any case, the demise of artist development became more realistic to talk about once the recorded music industry’s fortunes turned south in the new millenium. Artists may still take some years to find commercial success, but any subsidies toward this future now come from still-unsystematic sources — music placements on commercials and soundtracks, or maybe a tasteful sponsorship from a non-music consumer product company. And artists can still slog it out by themselves, via routes traditional (performance and touring) and new (viral videos, crowdsourcing.) But in any case, the path they take and the effort to make the journey are increasingly self-determined, entrepreneurial, and “DIY” in the broadest sense.

Musicians aren’t alone in this regard. A “free agent nation” (the title of a 2001 book by Daniel Pink) has been in the works easily since the new millenium, arguably before. Independent contractors, interns, contingent labor: the ranks of these and other categories of precarious workers have been in the empirical ascent since at least the 1990s.

What’s perhaps newer, and a case where musicians may very well be in the avant-guarde, is the ascent of the so-called sharing economy. Exhortations that creative workers should “brand themselves” to possible employers and audiences invariably include expectations that they should provide free samples of their wares “on spec.” (In the music industry, the common currency of the sharing economy is of course the free download.) The job-market rationale isn’t entirely irrational, but it’s an individual strategy that, following economic theory, inevitably lower employers’ wage expectations for everyone. It’s also increasingly hard to ignore how so many companies are looking to monetize our sharing, from Facebook to Kickstarter.