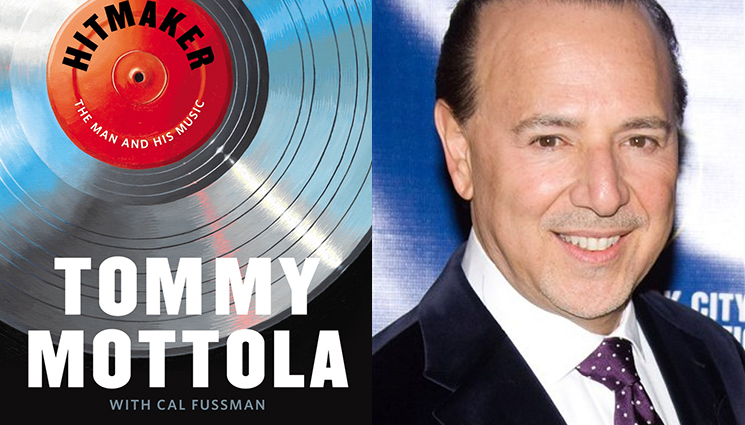

I’m fairly immune to the musical charms of the many recording artists whose careers were launched into stratosphere by Tommy Mottola, “one of the most powerful, visionary, and successful executives in the history of the music industry.” Mariah Carey, Daryl Hall & John Oates, Celine Dion, Gloria Estefan, New Kids on the Block, Shakira, Jennifer Lopez… Well, let me take that back: my immunity to the hits and deep tracks of Hall & Oates grows weaker year by year. In any case, Mottola has an autobiography out, Hitmaker: The Man and His Music. It’s no one’s idea of a gripping read, with a lack of literary flair extending to the tired book-cover design (most famously associated with Frederic Dannen’s 1980 book, Hit Men), but it effectively documents his central position at the helm of Sony Music through the last heyday of the music industry, before the MP3 liquidated the industry’s business model.

Give this to Mottola: he’s got a ‘pair of ears,’ as they say in the business — a real sense of what makes a hit. Among the first-person testimonials scattered throughout the book that give Hitmaker a much-needed sense of perspective, Daryl Hall has this to say:”When it comes down to art versus commerce, Tommy will invariably come out on the side of commerce” (pg. 104). (This testimonial is surely ambivalent, given the 3-year deep-freeze that Mottola, then Hall & Oates’ manager, put on Hall’s now roundly-appreciated 1980 solo album Sacred Songs, a collaboration with Robert Fripp.)

Furthermore, there’s an urban basis to Mottola’s ‘ears’. An Italian-American from the Bronx, he was steeped in the in-your-face culture and interethnic cultural stew of New York City. His first wife was a nice Jewish girl whose father was a legendary “record man” himself, the founder of ABC-Paramount Records. As Hitmaker quotes veteran music writer Dave Marsh:

To succeed in the record business, you have to understand the subtleties of race relations in America. For instance, Tommy knew how to position Mariah on the edge of three racial groups: black, white, and Latin. That was Tommy’s skill (pg. 253).

These ideas provide some context for the story I opened up Hitmaker to read about: how Tommy Mottola, then a hustling 25-year-old song plugger for Chappell Music, was immortalized in one of the most enchanting songs of the disco era, “Cherchez La Femme” by Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band.

It was more than a band, it was a carnival, almost a dozen kids from the streets of the Bronx who had grown up taking in the sounds of their neighborhoods. They blended Latin, black, and pop into the most unique music and visuals I’d ever come across. The music was only half of it. Watching the Savannah Band was like watching one of those Busby Berkeley movies from the thirties.

The group’s costumes were not costumes. Their costumes were their street clothes. One of the leads, August Darnell Browder, wore zoot suits every minute of every hour of every day. He probably slept in his zoot suit. Other guys in the band wore baggy pants and old newsboy caps. The lead singer, Cory Daye, wore antique dresses from the forties and fifties. They all took on their own personas and lived them. They were 100 percent the genine article. If these kinds would’ve had their feet on the ground and not gotten drunk on their first sip of sccess, they could’ve become one of the biggest acts in the world. Not only that, they’d still be here today! (pp. 107-8)

Fresh off his breakthrough success discovering and managing Hall and Oates, Mottola sniffed another winner in the Savannah Band. Led by Stony Browder, the group’s commitment to a unified sound and look had already baffled a handful of prospective labels, but Bronx native Mottola grasped their concept right away. He persuaded the Savannah to take him on as manager, got them signed to RCA Records, and shuffled them into the studio, where producer Sandy Linzer perfectly captured their big band jazz-meets-Latin disco fusion. In turn, August Darnell looked behind Mottola’s workaholic bluster to see the pathos of a man whose marriage had slipped away, turning out the melancholy lyric for the Savannah Band’s 1976 dance-your-blues-away single, “Cherchez la Femme.”

Tommy Mottola lives on the road

He lost his lady two months ago

Maybe he’ll find her, maybe he won’t

Oh, no, never, no, no

He sleeps in the back of his big gray Cadillac

Oh, my honey

Blowing his mind on cheap grass and wine

Oh, ain’t it crazy baby, yeah

Guess you can say, hey, hey,

That this man has learned his lesson,

Oh, oh, hey, hey

Now he’s alone, he’s got no woman and no home

For misery, oh-ho, cherchez la femme

You couldn’t walk down a street in New York [at the beginning of 1976] without hearing “Cherchez la Femme” blaring out of bodegas, boutiques, car radios, and night clubs. There are certain songs that will always be unique to the people who did them, because they stand for a moment in time and the vocal phrasing just cannot be duplicated. A lot of great singers sang “Cherchez la Femme,” but it will always be associated with Cory Daye’s voice. Cory was probably one of the best stylists I ever worked with, and what I mean by that is she had a sound and a phrasing that created a totally unique style. So that when the music, the time period, and her voice came together, something phenomenal was created that forced anyone listening to stop in their tracks. Something totally original had been created.

Hearing my name in “Cherchez la Femme” five times a day on the radio was so strange—almost surreal. At that age and at that time it became very intoxicating, even dangerous, and I was only their manager. You can imagine what it was doing to the Savannah Band (pp. 109-10).

Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band never duplicated the success of “Cherchez la Femme,” which is now remembered as one of the great one-hit wonders of the disco era. Two years later, they released a second album, Dr. Buzzard’s Original Savannah Band Meets King Penett, which is perhaps unfairly dismissed since, to my ears at least, there’s no significant drop in execution from the debut. But clearly there’s no hit there, either, and over the course of an entire second album, Browder’s elegant arrangements alongside Daye’s perennially tasteful vocals (and even the occasional vocal lead by Darnell) make for a fizzy, subdued cumulative effect.

Thus, as disco went both overground and deeper into libidinal rhythms in 1978, the Savannah Band were beginning to sound out of touch. But Mottola gives a behind-the-scenes account for their decline.

We’d schedule interviews for them at hotels and they’d show up late, six or eight at a time, carrying bags of laundry to be washed and dry-cleaned, then each of them would order two of the most expensive meals on the room service menu, one to eat just then, and the other to take home. Two of the three key members, Cory Daye and Stony Browder, were boyfriend and girlfriend. I remember getting a call late one night after they’d gotten into a major fight at the Continental Hyatt House on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles. They didn’t call it the Riot House for nothing. When Cory locked Stony out of her room, Stony opened up a window on a floor below and climbed up on the terraces like King Kong mounting the Empire State Building, then smashed through the sliding glass doors on Cory’s terrace and broke into her room. The group hired a screwy business manager who questioned everything that I was doing. Even the coleader of the band, August Darnell, who had a master’s degree and had taught English in high school, once pushed me to the point of a fistfight in my office. I needed to pour myself a scotch to calm down after that one.

[…] There was so much disarray around the Savannah Band [by 1979] that I broke off management ties. I didn’t need a crystal ball to see the collapse coming, and it was no great surprise when the band broke up after its third album failed to chart. August Darnell started another group called Kid Creole and the Coconuts, which had a great run in Europe, but it was a shadow of what the Savannah Band could’ve been (pp. 113, 115).

The hit man is entitled to his opinion; yes, nothing August Darnell released after the end of the Savannah Band had the same commercial chance given disco’s rapid decline. But I can’t let Mottola’s statement go unchallenged, because in so many important ways, the run of music Darnell made in the five years after Savannah Band remedied that band’s weaknesses. More to the point, it comprises a stellar body of work in an era filled with great music. With the funk-disco group Machine, he found those hard-hitting disco rhythms that his brother Stony never bothered with, and told another unforgettable lyric in their wonderful one hit, “There But For The Grace Of God Go I.”

With Kid Creole and the Coconuts, Darnell then brought that musical edge as well as — this is crucial — a sophisticated sense of humor back to the high-concept ambitions that motivated the Savannah Band. The Coconuts, a rotating trio of blonde vocalists fairly devoid of any jazz or R&B influence, could never match Cory Daye’s vocals, but (specifically through Adriana Kaegi, then Darnell’s wife) they brought a high-art element that led Darnell into musical theater and some of the most fantastic stage productions of the new wave era. The story of Kid Creole and the Coconuts is far too big to tell here, but a track like “Annie, I’m Not Your Daddy” (off 1982’s Tropical Gangsters, a.k.a. Wise Guy) draws upon and further extends so much of what made the Savannah Band genius, topping the whole thing off with an island vibe.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1SOkKMnPgQI

And not to be overlooked, Darnell’s work as the house producer at New York’s Ze Records yielded some of the freshest beats of postpunk-era downtown New York. Strut Records’ 2008 compilation Going Places: The August Darnell Sessions 1974-1982 is your first stop to hear Darnell’s remarkable productions, although you need to look elsewhere for fellow Savannah Band alum Andy Hernandez’s finest moment: “Me No Pop I,” recorded under his Kid Creole bandname Coati Mundi. Oh, and don’t forget no-wavers James Chance and the Contortions’ disco turn as James White and the Blacks; Darnell produced their 1979 album Off White.

10 comments

neo-classical music radio says:

Sep 23, 2014

enjoyed the page

Unknown Pleasures Chapter 21: Calling Mr. Love… | Love Letters to Euterpe says:

Oct 16, 2015

[…] for it’s opening [with credit actually] and tells the offhand tale of band supporter/plugger Tommy Mottola [yeah, that one] and his chaotic homelife. It was so infectious and melodic the first place I ever heard it was on the most straitlaced […]

Elaiine Williams says:

Aug 31, 2017

Interesting read. I stumbled on their first album in 1976 when I was 21. Being a nostalgia buff myself I feel instantly in love with their entire concept – all the way down to their fashion sense. Let me be clear I am not now nor ever was that sort of fan except for that one time. How I wish for those heady days again. Cory Daye was a musical force to be reckoned with – I always wondered what happened to her.

AndrewSGuthrie says:

Aug 12, 2018

Great article as I was searching for more information about Dr. Buzzard. Way back then I bought the 45rpm single Cherchez La Femme/Sunshower but I tended to spin the super-sweet Sunshower more often . . . but I held onto my singles and decades later both sides really started to grow on me . . . so much so that I started looking for a copy of the vinyl album, and then I found one (yesterday) for 5 euros in a used record store in Antwerp, Belgium.

Georgie KARVASALES says:

Oct 13, 2018

To Tommy,Barry Manilow,Elton.Tommy your book was Totally spot on!Every word was true.What NO one knew? Stony would BEAT Cory Horrendously & we both had to go into hiding Tommy you R A great man!!I was hit by Stony also He was jealous of Cory & one night punched her in the face so hard BLOOD from splatter was on the wall. I dialed Operater Cops came & told Cory to leave & we both separated into hiding I took MrLimelight her dog her Love of pets & THAT’S WHY THE SAVANNAH BAND broke up.I as Cory was afraid of that monster Cory DAYE WOULD HAVE BEEN BEATEN TO DEATH BY STONY BROWDER JR. UPDATE:Cory has been singing again. She Loves EVERYONE Mentioned Above! As I do her. Thank you Tommy your a great man! TOTALLY

Georgie KARVASALES says:

Aug 12, 2019

HITMAKER BY TOMMY MOTTOLA IS GENIUS! DR BUZZARDS ORIGINAL SAVANNAH BAND’S AUGUST DARNELL & BROTHER STONY BROWDER WERE HORRENDOUS MEN, STONEY ALWAYS PHYSICALLY BEAT MY BEST FRIEND ALMOST TO DEATH MANY,MANY TIMES CORY & ME HER SURFER BOY AS SHE ALWAYS CALLED ME IN CALIFORNIA LIVING NEXT DOOR NEIGHBORS & I HAD NEVER SEEN OR HEARD OF THE BAND CORY & I MET AS FRIENDS! I HAD NO CLUE THEY WERE IN CA.NOMINATED FOR A GRAMMY. UNTIL MUCH LATER & I DIDN’T REALLY CARE. I SAW STONY PHYSICALLY PUNCH & BEAT CORY TO A PULP & I WAS SICKENED CORY ASKED ME IF I WOULD GO BACK TO N.Y.C. WITH HER, I DID & MET TOMMY WHO WAS SO GENUINE,KIND & THE MOST CARING PERSON, FRIEND EVER, CORY & HER “georgie” WERE LIVING ON RIVERSIDE DR. STONEY PUNCHED CORY IN THE FACE & OUT OF HER EAR CAME A MASSIVE AMOUNT OF BLOOD PRESSURE THAT SPLATTERED ON THE WALL.I DIALED THE OPERATOR TO SEND THE POLICE, THEY CAME & SAID TO CORY, ” LADY YOU HAVE TO LEAVE”!! THERE WERE NO LAW’S @ THE TIME,CORY WENT INTO HIDING,I SAID TO STONY BROWDER JR. W/ANGRY TEARS? WHY DO YOU HIT WOMEN? HE SLAPPED ME SO HARD IN THE FACE & SAID TO ME YOU LIKE IT DON’T YOU? & THREATENED IF I TOLD ANYONE…..ALL I HAD WAS MR.LIMELIGHT CORY’S BLONDE COCKER SPANIEL & MR.LIMELIGHT SNUCK OUT ALSO WENT INTO HIDING IN HELL. THE SAVANNAH BAND NO MORE. STONEY & AUGUST DARNELL HIS BROTHER THOUGHT THEY COULD DO IT ALL WITH THE ALBUM’S AFTER & IT NEVER MADE IT. NOW, TOMMY MOTTOLA TOOK CORY & ME UNDER HIS WINGS & WE DIDN’T HAVE A POT TO PISS IN & TOMMY “God love him” A MAN WITH THE BIGGEST HEART OF GOLD GAVE CORY A CONTRACT UNDER HIS NEW LABEL ” CHAMPION ENTERTAINMENT” WITH SANDY LINZER WHO PRODUCED: CORY & ME BY CORY DAYE. TOMMY WOULD CALL TO SEE HOW SHE WAS DOING & I ANSWERED & SHE WAS SLEEPING OR OUT, I WOULD GO TO TOMMY’S OFC. & I WAS PETRIFIED IF STONY BROWDER JR OR HIS BROTHER AUGUST DARNELL EVER FOUND OUT WHAT WOULD HAPPEN IF I TOLD TOMMY THE HORRENDOUS HELL WHAT WERE GOING THROUGH. I ASSUME PEOPLE THOUGHT CORY LEFT THE BAND FOR WHAT’S CALLED L.S.D. aka LEAD SINGER’S DISEASE. NOT TRUE @ ALL. CORY TOLD ME,” georgie, TINA TURNER HAS NOTHING ON ME”Thank you TOMMY YOU WERE ALWAYS THERE FOR CORY & ME AND YOU ARE LOVED FOR JUST BEING YOU..

GEORGE says:

Aug 18, 2019

BARRY, ELTON: THANK YOU SO MUCH IF YOU WOULD GET GET AHOLD OF CORY ON HER FACEBOOK PAGE & WEBSITE SHE HAS ALWAYS WANTED TO KNOW WHERE TONY KING HAS BEEN & ONE LAST THING IS IF SHE COULD RECORD AGAIN? Don’t mention her georgie ok?

Georgie KARVASALES says:

Aug 18, 2019

THANK YOU FOR YOUR Kind Hearts ❤️ at another “Everything” !

Georgie says:

Oct 25, 2019

WHAT WOULD YOU DO IN CORY’S SITUATION WHEN THERE WERE NO RULES ON MEN BEATINGS OF WOMEN? GEORGIE WAS 20 CORY WAS 23 yrs OLD

Georgie says:

Jan 22, 2020

I DO NOT FOR A MILLISECOND HESITATE TO TOMMY MOTTOLA IS PURELY A GREAT CARING MAN AS WELL AS BRILLIANT & I DEFINITELY REALIZE THAT ANYONE WHO DISAGREE’S IS JEALOUS OF THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS TOMMY HAS PROVEN THROUGH HIS MUSIC INSIGHT’S & A TALENT NO-ONE CAN DENY.