Remember the bands that formed in college? You heard them at dorm parties, frat parties, apartment parties, the campus bar, battle-of-the-bands competitions, and impromptu outdoor settings. They practiced in dorm rooms, dorm basements, conservatory and theater rooms, backyard sheds, and laundry rooms, amusing/irritating neighbors and passers-by. Many college rockers and rappers dreamed of making it big after graduation, maybe even swearing loyalty to bandmates that they would “be in this together.” Others played music just for fun and extrinsic rewards (sex, drugs, rock’n’roll, status, etc.), leaving or breaking up the band by graduation with little regret. You might still have a CD from one of these groups in your collection, testimony to the fact that you “knew them when” before they most likely fell into obscurity.

Remember the surplus musicians and would-be musicians, the ones who couldn’t get anything musically happening in their college years, although not for the lack of trying? There was the guy who played his acoustic guitar in the quad, the trio trading rhymes at the lunchtable, the roommate whose equipment lay stacked, untouched, in the corner of the apartment. For every thousand great band names brainstormed at parties, dorm rooms, and campus jobs, maybe a hundred “first practices” were ever convened, with less than a dozen ever gelling into a real unit. Out of the frustration or idleness of their college years, a few of these dormant talents established bona fide musical careers, surprising their friends and becoming the talk of alumni gatherings after graduation.

WHY WE MIGHT STUDY THE COLLEGE MUSIC SCENE

The college music scene is largely overlooked as a site for study. For one reason, many musicians understandably would like to dissassociate themself from their alma mater. Getting a degree from an institution of higher education is increasingly an expensive accomplishment that can suggest a comfortable, bourgeois background. What musician looking to project an image of political rebellion or subcultural sensibility would want to announce that? College is also regarded as an unsettled, transitional period of life when young people try on new ideas, tastes, activities, and fashions. Memories of the clothes we wore, the music we played, and the haircuts we had when we were 19 years old generally make for cheap laughs, not a heroic bildungsroman. What musician hoping to convey a confidence of musical self would want to be tied to the place and time of developmental flux and discarded baggage?

Yet aside from the pleasures of nostalgia or laughs, there are intellectually worthwhile reasons to revisit and thinking carefully about the college band scene. Intuitively, we recognize that looking at musicians’ alma mater might shed light on the music and the influences of the lucky few who break out of them. To cite a well-known example, Britain’s legacy in the 1950s and 60s of sustaining and advancing American genres like blues and jazz is often credited to the country’s art schools, where students like Keith Richards and Eric Clapton exchanged records and honed their chops with like-minded musos in classroom studios and campus commons. Institutionally, colleges enroll populations of young people in specific socioeconomic and cultural mixes, giving them formal and (probably more important) informal opportunities to ‘come of age’ developmentally, intellectually and creatively. The effects of these institutional settings on the music can be significant, as Owen Hatherley’s thesis about Pulp as Britain’s “last art school band” suggests:

From the early 1970s until the 1990s, hundreds of musicians from working or lower-middle class backgrounds, many educated at art schools, claiming state benefits and living in bedsits or council flats weeks before they found themselves staying at five-star hotels, were thrown up in the UK. From Roxy Music to the Smiths, from the Associates to the Pet Shop Boys, all balanced sexuality and literacy, ostentatious performance and austere rectitude, raging ambition and class resentment, translating it into records balancing experimentation with populist cohesion; it was possible to read the lyric sheets without embarrassment. You could dance to it.

At some point in the 1990s this literary-experimental pop tradition disappeared. Some reasons are structural – workfare schemes meant that claiming the dole as a “musicians’ grant” was less and less practicable, art schools were absorbed by universities, council flats were unobtainable for any but the desperate, and squats became rarer, so the unstable alliance between bohemia and estate was broken. The result was a striking homogeneity of class as much as of sound. In October 2010, according to an oft-cited statistic, 60% of artists in the UK top 10 had been to public school, compared with 1% in 1990.

For many urbanists, an interesting question is: how do college music scenes relate to the cities in which they’re located? The creative-economy paradigm views higher-education institutions as multifaceted assets for urban economic development. They generate talent and innovations to be absorbed by firms, the thinking goes here, while they sustain cultural amenities that attract creative workers at play. This perspective regards college music scenes instrumentally, treating them as one element in a city or region’s amenity infrastructure. In some places, they develop further to anchor or brand a city’s export-oriented cultural infrastructure, as illustrated by the college-music heydays of 1980s Athens, GA (University of Georgia) or 1990s Olympia, WA (Evergreen State College).

A variety of other questions pertain to the ways that college music scenes relate to their institutional settings. For instance, how do these scenes affect the ways colleges and universities market themselves? Today, indie rock seems disproportionately represented by graduates of prestigious eastern institutions, but do the latter advertise or otherwise exploit their graduates’ musical careers? For instance, does little Wesleyan University (“the coolest college ever,” states the Village Voice with tongue in cheek) include MGMT, Das Racist and Santogold in their materials for prospective students? Bard College (the #1 hipster college, according to a 2012 HuffPost article) maintains a website archiving the bands that formed during their college years. Interestingly, the Bard website says nothing on the groups that led to Steely Dan, probably Bard’s most famous popular music success story (whose ambivalence about their alma mater is memorialized in “My Old School”).

TRAJECTORIES OF CREATIVE LIVES

The level of analysis in such questions are collective or institutional. They might be answered through aggregate statistics by counting graduates in musical occupations, measuring a college town’s musical infrastructure, surveying universities’ admissions/alumni offices, and so on. By contrast, a deeper historical/ethnographic examination into particular college music scenes could offer rich qualitative insights into the mobilization of creative lives.

A guiding concept here is status attainment, which refers to how people enter occupations, move through their careers, and take on distinct sets of values, worldviews and self-understandings. These dimensions are implicit in the occupational prestige scales that sociologists study, or at least used to back when occupations were stable and widely understood categories. In today’s mercurial world of work, where ‘value-adding’ creative pursuits shouldn’t necessarily be confused with full-time jobs, status attainment highlights how individuals acquire the technical skills, aesthetic distinctions, and cognitive frameworks that make for musical lives. To put this in the language of contemporary urban debates, status attainment is about the longer-term development of the “creative ethos” (or, for critics of Richard Florida’s concept, the yuppie/hipster weltanschauung) that has revitalized many urban economies and polarized many cities of late.

So far as I know, no one has studied the college music scene as a context for status attainment in this sense. But this is a line of inquiry pursued more broadly by scholars like Bill Bielby, who study the organizational dynamics of status attainment in people’s careers: how far people can go in a line of work, where they hit roadblocks and ceilings, and how these trajectories are shaped by specific organizations, industries and professions. (Disclosure: Bielby is my former grad school professor, and I occasion play with his pick-up band of conference-attending sociologists, Thin Vitae.) A relevant study is one that Bielby presented to the American Sociological Association in his 2003 presidential address, in which he examined “grassroots cultural production” by looking at Chicago-area teenage bands “in the early days of rock and roll, [when] grassroots performance was an ’empty field'” (pg. 10).

I define a teenage band as any local teenage rock and roll performance group that had a drummer, at least one electric guitarist, a band name, and a business card. With this definition, I have identified most if not all of the local bands of this region from the post-Elvis, pre-Beatles era (1958 through 1963) (pg. 3).

(Of course, 1958-63 was a period when the real-life issues hinted at by sociological terms like “status attainment” and “subcultural involvement” were charged with high stakes for young people and their parents. [“YOU’RE GROUNDED FOR LIFE!”] It’s a different world today. Watch a prefab teen punk group execute choreographed stage moves on the Disney Channel, and you’ll quickly appreciate how rock, hip hop and pop music today are thoroughly incorporated into dominant modes of adolescent life and social reproduction. Leaping ahead to the other side of the college years, a whole field of hipster studies revolves around the question of whether participating in often-extreme musical styles and affiliated lifestyles retains any kind of transgressive qualities in today’s consumer/lifestyle economy.)

MUSICAL STYLES, MUSICAL SELVES

In developing a theoretical framework that inserts colleges and universities into the status attainment of musical lives, we might put aside the idiosyncratic dynamics of chance and biography (e.g., Donald Fagen and Walter Becker met at Bard College). More systematic influences of college music scenes on musicians can be ascertained in the collective musical style that each institution cultivates. By ‘style,’ I don’t mean just the musical idioms, techniques, and inspirations that musicians and music critics usually associate with particular places or eras. (Incidentally, I suspect such traditional elements of ‘style’ are less subconsciously absorbed and more directly mediated by the aptitude and agency of individual musicians and groups than is often appreciated). Instead, collective musical style involves the expressive, symbolic components of constructing a musical self in interaction with others.

My language here comes straight from the forthcoming book by sociologists Amy Binder and Kate Wood, Becoming Right: How Campuses Shape Young Conservatives (Princeton University Press, 2013). (More disclosure: Kate Wood is a former student of mine and graciously showed me the manuscript while still in press.) Comparing the dynamics of college students’ musical development to their political orientations may seem odd, but as Binder and Wood argue, “The learning of group styles by means of shared culture and organizational features on campus is far from limited to the production of conservative selves.” Read these two programmatic statements from Binder and Wood, and substitute “musical” for “conservative” and “political” to see how their framework might apply to an analysis of college music scenes.

In presenting the argument that universities have a large influence on conservative political development, we must introduce two caveats. First, to argue that political style is an organizational accomplishment that occurs on campuses is not to claim that students arrive at college with no ideological commitments derived from family, community, media exposure, or prior political and schooling experiences, or that students are blank slates to be written on by educational institutions. Students’ prior identities are important and must be accounted for, even while we observe that once students enter a university, that institution’s existing organizational structures and cultural repertoires channel them into distinctive types of conservative style. Second, and related, students are not automatons molded seamlessly into these styles. There is plenty of agency to go around, as students take stock of their identities on campus and think strategically about how their actions will ultimately connect with their future careers and social lives. There is evidence in our cases that students assess their options, and then sometimes actively defy dominant styles by taking up submerged styles, or create new hybrid forms of expression out of multiple different styles. They also sometimes decide to opt out of political life on campus if the conservative organizations they are interested in don’t seem like the right fit. Or they plot to put together a new slate of club officers when the time is right. [Chapter 1]

Following work being done by Tim Hallett and Marc Ventresca and a few others in a body of research called inhabited institutions, we see broader cultural repertoires and people in local settings as “doubly embedded,” such that people’s “interactions take place within, and are shaped by, broader institutional contexts,” but the practical meaning of their actions emerges locally through social interaction. Conservative style is a form of action that both filters from the top down and emerges from the bottom up, getting worked out in the middle. Keeping track of all these levels of meaning—from the most personal and privately held to the most widely shared and disseminated—allows us to comprehend how and why students use different dominant and submerged conservative styles on different campuses. [Chapter 8]

In the case of college music scenes, the “top down” wouldn’t necessarily be limited to the campus gates since musicians can also seek audiences outside the student body — indeed, this is how many bands go about making it big. Geographical location and opportunities to participate in regional music scenes are thus further variables of organizational context, perhaps among the most important ones. To illustrate these factors and the many others at work in college music scenes, let me sketch the scenes at two very different higher-education institutions that I’m familiar with, before concluding on some formal hypotheses for study.

CASE STUDY #1: VASSAR COLLEGE

My current place of employment, Vassar College is a highly exclusive four-year liberal arts college in Poughkeepsie, a small city in the Hudson Valley area of New York. It’s a good example of the small, private institution type found scattered across the U.S., particularly in the northeast and midwest. The college is small (around 2600 students) and draws from an international body of students. In the latest freshman class, Vassar’s top feeder states were New York (disproportionately from New York City), California, Massachusetts, New Jersey and Pennsylvania — all quite “blue states” politically and culturally. Very few Vassar students come from local high schools.

An incomplete list of bands who came from Vassar College includes Love Child (whose guitarist Alan Licht remains active in avant-rock circles), the Sweet Things, the Bravery, Beach House, Throw Me The Statue, Genghis Tron [and, most recently, MS MR – ed.]. Love Child, the Sweet Things, and Genghis Tron made a go of it (in indie rock for the first two, underground metal for the third) as the musical unit they formed in college. The Bravery, who made a splash in alt-rock circles last decade, were formed by three students who played in the college band Skabba the Hutt (a “mock-ska band,” Wikipedia notes). Beach House and Throw Me The Statue were groups formed after their key players (Victoria LeGrand and Scott Reitherman, respectively) graduated.

Two solo musicians of recent note who came from Vassar College are Howard Fishman and Rachel Yamagata. Fishman is remembered by some classmates as the proverbial guy on the quad playing a guitar; after graduation, he made a respectable impact as a purveyor of New Orleans-inspired folk and jazz. Yamagata transferred to Vassar College from Northwestern University; having established a career as a performer and songwriter in the confessional vein of Fiona Apple, she’s returned to the region as a part-time resident of Woodstock. Depending on who you ask, famous musical alumni from Vassar College include the Beastie Boys’ Mike Diamond and DJ/producer Mark Ronson, both of whom spent a short time at the college before moving on superstardom and NYU, respectively.

Vassar College has a reputation for an erudite, critical-minded, worldly and arty student body — a milieu that possibly manifests in the kinds of music associated with these bands and musicians, whether by college-age socialization or post hoc attribution. At the same time, the institution has little cultural connection to the City of Poughkeepsie, the deindustrialized, stigmatized city outside its front door. Few Vassar students find their way into the small handful of dance clubs featuring hip hop and R&B, or the bars and venues where heavy metal and punk/emo bands play. The holds true for Vassar bands as well: most never play a gig at a Poughkeepsie nightclub or bar off campus. One reason is that these venues are 21-and-over, alcohol-vending establishments that would necessarily exclude about three-fourths of the student body. But I suspect the main factor has less to do with such supply-side factors, and more with the formal and informal insularity of College, which shapes student life regardless of musical interest.

The college’s insularity begins with its residential policy. Almost all students live in dormitories on campus or (for some seniors) in college-owned student housing across the street. Outside the campus, the Arlington neighborhood provides little in the way of college-town amenities; the handful of bars, cafés, restaurants, and tattoo parlors do much better business serving local residents. For concerts, nightlife and cultural identification off campus, Vassar students are more likely to take the commuter rail 90 miles south to New York City. Historically, the college also taps New York City for its extracurricular musical programming, from indie rockers and dance DJs playing late night at the campus bar, to professional jazz musicians and combos performing before students and faculty audiences, to touring alt-rock and hip hop acts playing high profile on-campus concerts once or twice a year.

In this small, enclosed college setting, musically inclined students generally don’t have to look hard to identify others with the same tastes or ambitions. At present, indie rock (i.e., what we used to call college radio in the 80s and 90s) is arguably the favored genre among Vassar bands. Occasionally a student trained in classical music, either at the college or before, will put together a more mannered “chamber pop” group. However, a good number of ensembles play jazz (which is taught in the Music Department) and other styles that require serious chops (funk, afrobeat, etc.). The college radio station looms large at Vassar College, both in wattage and as a gathering place for music geeks of an indie-rock persuasion. Meanwhile, the campus bar and student parties are more likely to play hip hop, EDM, pop and alternative rock. There’s also a remarkable number of a capella groups that students can audition for.

These aren’t merely the predominant genres of music heard on campus; at an institution as small as Vassar, they’re the styles associated with students in a close-knit residential community. Someone who favors sounds outside of these genres — a black metal obsessive or a Juggalo, for instance — will become quickly known as an afficianado of outré or room-clearing sounds. Fortunately for their social life, they can mitigate this reputation through all the other encounters and roles they have with their fellow students in the 24/7 total institution of the residential college.

Many students appropriate dorm rooms and basements for band practice and jamming, although complaints by fellow students can bring an end to sonically extreme collaborations. Intrepid bands can find practice space well off campus; monthly rents are fairly cheap, making access to a car the more likely limiting factor. (Few Vassar students have cars on campus, a reflection of how self-contained residential life is.) Occasionally an off-campus building (not college owned) becomes designated a “band house,” complete with shabby instruments and equipment, that is passed on among exclusive cohorts of students (see the video below). These residences often double as crash pads for low-profile touring bands who play campus gigs; out of such DIY generosity, contacts are established that can reciprocate at a later date with gig support, technical advice, or basic exposure to cool new sounds that can advance Vassar students’ musical lives.

This raises a more general point about social capital. Another reputation Vassar College has is as a rich kid’s school. It’s unfair as a generalization across the student body; like many top-tier institutions, Vassar has become increasingly generous with student aid, and students can earn money through campus work-study jobs. However, I think it’s safer to hypothesize that musically inclined students arrive with a good deal of savvy and social capital in musical undertakings. Some of this reflects the media interest in and internet-based diffusion of DIY expertise found across the board, in music and other lifestyle/creative ventures, in recent years. But some of it is local in origin, specifically in terms of the places where students come from and where they move to.

For instance, whether or not students come to Vassar College with musical skills (and a surprising number do), many arrive with musical ambitions already hatched with childhood friends who are scattered across other higher-education institutions. A friend well-placed at a student activities group or college radio station elsewhere can invite a Vassar band to play before receptive, non-local college audiences. This is a highly effective way to maximize exposure and, even if nothing becomes of the college band, to broaden student musicians’ career/creative horizons. Conveniently, these connections also let bands leapfrog over the trenches of Poughkeepsie venues.

This network-based promotion of musical careers works after graduation as well, of course. A good number of Vassar students, particularly musically inclined ones, move to Brooklyn, Baltimore and other urban bastions of educated 20-somethings. The pickings are harder to come by here in terms of gigs and exposure for Vassar College bands, but friends who have graduated can nonetheless give their friends back on campus a leg in the musical ‘real world,’ so to speak. At the very least, such connections help would-be musicians who move to hipster neighborhoods (and places like Williamsburg are filled with students from exclusive colleges and universities) hit the ground running, with less trial and error about where to live and who to start a band with.

CASE STUDY #2: UCLA

My undergraduate alma mater, the University of California at Los Angeles is a large public university of around 35,000 students. It’s a good example of the large state school found across the U.S., although few others are located in a world-class music industry city. Most UCLA students are undergraduates, but its many graduate and professional programs (and, for that matter, the difficulty undergrads have in getting all their required classes for the Bachelors degree) mean students well into their 20s and 30s make up a good part of the college population. This feature breaks up the intense 18-22-year-old atmosphere found in a 4-year college like Vassar.

UCLA is very much a public institution within the city, with marquee-level college sports teams, an esteemed research hospital, extension classes, high school summer programs, and community events and festivals bringing an outside population to the campus everyday. Furthermore, most students live off campus after their first year (a few unlucky freshmen don’t even get that). The surrounding Westwood neighborhood is the largest off-campus residence for UCLA students, with innumerable apartment buildings and fraternity/sorority houses, but personal predilection, age and household size lead many students to live farther out into Los Angeles. Consequently, UCLA isn’t a self-contained, 24/7 total institution for most of its students; for some, it’s essentially a commuter college.

Given the institution’s size and L.A.’s stature as a music capital, the list of bands and musicians who came from UCLA is predictably large, practically incalculable. The class of ’65 alone included Jim Morrison and Ray Manzarek (their accidental meet-up a year later was the storied beginning of the Doors), Jan Berry of Jan & Dean (whose hitmaking years coincided with college — partner Dean Torrence went to USC), and Randy Newman. In the mid-60s, the cult electronic group the United States of America started out of a collaboration in the university’s New Music Workshop. The Mael brothers Ron and Russell placed recordings from their offbeat studio project Hafnelson in Ron’s 1970 student film before beginning a 40+year career as Sparks. Greg and Raymond Ginn earned their degrees in ’75 and ’77 before launching hardcore punk label SST Records as, respectively, Black Flag founder/guitarist and (as Raymond Pettibon) the house illustrator. (UCLA now features Greg Ginn in its online marketing materials.) These artists weren’t college bands per se, since they either pursued music primarily outside of a college setting (Jan & Dean, Sparks), or they didn’t form the bands they’re really known for until after graduation (the most notable recent example being Linkin Park).

By contrast, some UCLA bands had a very clear on-campus genesis. L.A. punk trio the Urinals formed in 1978 out of the Dykstra Hall dormitory. As they recall from this period:

A scene was beginning to spring up at UCLA, with homegrown talent like NEEF, PROJECT 197 (Bruce Licher’s initial project, pre-SAVAGE REPUBLIC), which featured Kevin on its release, and ZILCH, who similarly released records. Soon to come was the LEAVING TRAINS, who, like the URINALS and the TUNNELTONES (Licher’s next band), staked out their own parking structure rehearsal space on weekends to take advantage of the free electricity and the massive sound which results when amplified distortion meets a large reflective concrete surface. (This sound is similar to that found on the “Sex/Go Away Girl” single, which was recorded in the basement weight-room of Dykstra Hall, during a weightlifting session!)

UCLA’s urban context means we can’t assume the overlap of student musicians, student audience, and college setting that characterizes the “college band” at a non-urban, socially insular institution like Vassar. As economic geographers have shown, labor markets are what makes cities and regions thriving sites for culture industries, and UCLA is very much embedded in a larger musical talent pool. A trip off campus to a record store or guitar shop can tantalize the would-be musician with “musician wanted” flyers, as does a scan classified ads in free local periodicals. When bands are being formed and playing gigs throughout the city all the time, UCLA students don’t have to restrict themselves to the college population to find bandmates; indeed, it can be difficult, or at least contrived, to finalize a line-up by selecting from only fellow students.

Alongside the pull of urban labor markets, institutional factors push many college into the city. The university’s massive size provides anonymity for any students seeking it. This helps explain the appeal of fraternities and sororities, as well as other student tribes like housing coops or college radio stations, since these provide a manageable focal point for student life. This invisibility also gives student musicians license to pursue music that’s not necessarily aimed at college audiences, and to withdraw involvement in college life in order to support their musical supports.

A good example of this from my years at UCLA is glam metal. In the late 80s, the so-called hair metal scene was raging five miles away down Sunset Boulevard. For reasons of class, cultural capital, and marketing, glam metal was never a popular style among UCLA students. (Skid row singer Sebastian Bach was very insightful to call alternative music’s ascendancy in the 90s as “the revenge of the college people”.) And yet a small number of UCLA students were in glam metal bands that played on the Sunset Strip. In class their long hair wouldn’t be teased up, and they’d pay as much attention to the lecture as the next student, but they would live off campus, and they could inconspicuously depart themselves from their fellow students to go practice or play gigs, the way others might go to a job waiting tables. Like any other student whose life was based off campus, these musicians faced no ostracism or other social repercussions, least of all for the kind of music they played.

Another example from the same time is the short but remarkable list of working punk musicians attending UCLA: Kira Roessler from Black Flag and DC3 (’85), Joe Escalante from the Vandals (’85), Greg Graffin (double major B.A. ’87, M.S. ’90). Tellingly, I didn’t know about these UCLA musicians until researching this essay; their bands were based on the other side of L.A., making them de facto commuter students. The many ways to be educated at UCLA outside of a conventional 4-year undergraduate sequence makes it easier for musicians to escape the gravity of the college music scene, and the general attention of the student body. For example, Shakira recently took a summer extension course at UCLA; as much as they might want to, almost no one considers her a “UCLA musician.” It’s almost impossible to estimate the number of musicians who graduated the institution, or to get a bead on the many genres and formats of music they might play: working jazz musicians who might sideline in a dance band, classical musicians playing chamber music for weddings, composers who went on to soundtrack film and TV, and so on. More generally, UCLA makes significant contributions to Southern California’s laborforce via the students who graduate from or simply take some courses from the university before taking up a post-college life in the region. Despite its international stature, UCLA is very much a ‘local institution” — a key issue for understanding the musical activities of its students.

The diffusion of UCLA students’ residence, jobs, and recreational activities off campus means the college music scene is less important as a breeding ground for student musicians (still the draw of the coffeeshop open mic night) and more important as a sustaining habitat for bands from around the city. For instance, I remember was a student employee of UCLA’s Audio Visual Services who always seemed to have his acoustic guitar with him; this was John McCrea, who moved after graduation to Sacramento to form the band Cake. (As one alum recalled, “The AVS employee lounge served mostly as guitar-case storage back in the day.”) In fact, certain kinds of college jobs are ideal for struggling musicians because they pay competitively, offer flexible scheduling, and don’t necessarily discriminate against dreadlocks, tattoos, or other subcultural fashions; often managed by university graduates, college offices can be more understanding than most employers when musicians (current students or graduates) need to rearrange schedules or take unexpected leaves.

Needless to say, the college music scene sustains bands with that most valuable of resources, gigs. At UCLA there are countless parties and social events that need bands. In the late 80s, black fraternities hired rap crews, white fraternities hired ska and jam bands, and the housing coop featured art rock and punk bands. No doubt the party soundtrack in these off-campus settings has changed since then. Regular parties in students’ apartments and houses may feature bands playing for much less, such as beer and gas money. DJs have always been around as mobile party units; an open question today is whether they have eclipsed traditional bands thanks to the new popularity of EDM. Altogether, these performers constitute the college’s informal music programming, where audiences are regulated by invitation and doorman.

Then there’s the university’s formal music programming, very little of which (namely, the annual Spring Sing talent show) draws on UCLA bands. The university’s college activities office is quite large, advertises its events in local periodicals, and draws prominent local bands. Examples: in 1986, I saw the Red Hot Chili Peppers and a pre-Appetite Guns’n’Roses open for the Dickies; the show had a full-page ad in the LA Weekly. That same year an up-and-coming Janes Addiction played a noon-time concert at the Cooperage eatery; I saw them bowling in the student union’s bowling alley before the show. An empirical question is whether local bands booked by university events programmers overlap with the bands playing parties and fraternities. When I was at UCLA, these were two different circuits of bands, perhaps due to the depth and professionalism of the larger L.A. music scene. Of course, the university also maintains an extensive schedule of classical, jazz, world music and modern music performances through its music departments and performing arts offices, which advertise in the daily LA Times. These performances deliberately bring the public onto campus, which among other things gives the students and staff who book these events considerable status among L.A.’s music bookers.

At UCLA, the college music scene immerses music fans among the college population to the greater city’s musical underground (or whatever we could call the most important bars and venues to hear the lastest bands) to a surprising degree. UCLA students get exposed not just to the latest sounds but to the fashions, lifestyles and presentation of self of the city’s nightlife denizens. For young music fans and would-be clubgoers, access to this nocturnal capital (to use Dave Grazian’s term) has long been the draw of going to college in a big city. In a sprawling, pedestrian-unfriendly city like L.A., these institutional features (by design?) compensate for the disadvantage UCLA has compared to schools with easier access to urban nightlife and cultural amenities. For students playing in bands, and for others still incubating the idea for later realization after graduation, seeing bands and acquiring nocturnal capital via the college music scene comprise skillsets that can be as important, maybe more, than the skills that come from spending hours alone practicing scales or paradiddles.

CONCEPTS AND HYPOTHESES FOR STUDY

This brief comparison raises more questions than it answers. If it’s not evident by now, this essay is in fact a proposal for a research project I hope to undertake. Below, I suggest the concepts and hypotheses I’d like to study more systematically — at Vassar, UCLA, and other colleges and universities.

Dependent variable: Status attainment

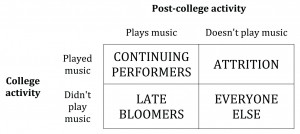

To begin, there’s the issue of status attainment — in this case, of how college students take on a musical life. Usually we ask “Did that band come from a certain college” retrospectively of a band that’s active in the present, i.e., after they graduated from college. As the table below indicates, this scenario is only one way that someone can “be a musician” from a certain college: as a continuing performer. An important question here is, just what has remained continuous since college: playing with fellow alumni, even playing with the same band formed in college? If neither of those is the case, then we might look elsewhere to see what else from college (besides accumulating 1-4 or more years of performing experience) shapes continuing performers’ careers and styles.

The idea of the “famous musician from a certain college” doesn’t exclude the possibility that the musician didn’t play music in their college years. They may have only pursued a musical career after graduation, in what I call the late bloomer scenario for lack of a better word. In fact, there’s at least two sub-categories here: those who entered college with musical/performing experience but put their playing on hold during their college years, and those genuine late bloomers who never played music in a serious way (e.g., playing with other musicians) until after college. Which one is more prevalent? Why do some musicians not play during college, given the opportunities presented by the college music scene or more formal musical education? And once again, what do these musicians take from college: a network of alumni collaborators, exposure to certain aesthetics or sounds, etc.

Finally, some students stop playing music after college—the scenario of attrition. Why do they stop? Did they graduate having acquired a musical self in their college years, and in what ways?

Dependent variable: the college music scene

What are the essential features of any one university or college’s music scene? Intuitively, we imagine a scene can be characterized by genre (rock, indie-rock, hip hop, punk/emo, etc.), technical traditions (jamming, ‘non-musical’ conceptual/art projects, solo singer-songwriters), and influences (the Grateful Dead, Radiohead, etc.). Being cautious not to overgeneralize, we might anticipate that more than one genre, tradition or influence can characterize a scene. Furthermore, it’s an open question whether there are latent affinities among competing genres, traditions and influences (e.g., underground metal musicians resonate aesthetically more with indie rock than commercial heavy metal).

Thinking about the non-musicological elements of ‘musical style,’ we can also seek to characterize college music scenes in terms of prevailing modes by which students construct a musical self in interaction with others. How important are musical taste and (separately) musician status as markers of student identity in different colleges and universities? In which college contexts are students recognized and interacted with for their taste and status: within particular group contexts (among close friends, in college radio stations, etc.), or across many domains of college life? How do student musicians relate to the music scene at their college or university: e.g., do they identify with their fellow college bands and audiences, reject them, or effectively pay no mind to them at all in creating and promoting their music? Presuming that their college years influence musicians in some way, how reflexive are musicians about this influence — is it something they’re aware of while in college, or does it take some time after graduation to perceive or acknowledge an influence?

Independent variables: institutional features of the college as institution

A number of factors and contexts could affect or mediate various aspects of these two dependent variables. First, I address the internal features specific to the college or university where musicians come from.

What’s the size of student body? This factor could affect the talent pool and student status hierarchies that musicians draw upon.

How does the college select for a certain type of student population? For instance, what’s the mix of student body characteristics along educational, socioeconomic, cultural and geographical lines? What are the residential situations at an institution: proportion of students living off campus, housing stock (small apartments versus stand-alone houses)? We should anticipate that musicians might not reflect typical student body characteristics.

Does the college offer formal opportunities for musical training: music departments and classes, opportunities to support theater productions, and so on?

What kinds of informal opportunities (outside of forming bands) exist for students’ musical development: extracurricular activities (a capella groups), supporting organizations (student associations, college radio stations), third spaces (outdoor quads, dorm commons)?

What’s the infrastructure for musical practice: rehearsal spaces for student activities, instruments or rehearsal spaces owned “in commons”, etc.? And for musical performance: campus bars, coffeeshops, battle of the bands, etc.?

Independent variables: urban/regional location of college

Colleges and universities are located in places that may stimulate, restrict, or otherwise shape the development of student musicians and the college music scene.

What are the features of the music scene around the college? Are there bands to join, talent to enlist, venues to play, gatekeepers to solicit (local media, music industry)?

Are there affinities or congruences between the college scene and the city’s scene: shared tastes in live music, shared tastes in nightlife (do they party the same way?), socioeconomic/cultural/age disparities between “town and gown”?

How do student musicians access the external music scene: distance from student residences, transportation infrastructure, public sphere for talent pools and self-promotion (classified ads, locations for “musicians wanted” flyers), etc.?

Does the larger music scene have a legacy that draws or repels college bands? We might anticipate that student musicians might choose to enroll in institutions based on well-known urban/regional scenes (i.e., selection effects).

Historical shifts

Not only do college music scenes vary by institution, but we might expect them to have evolved over time. My comparison earlier between Vassar and UCLA doesn’t correspond to the same period; nor do I suggest they comprise a coherent picture of the shifts in college music scenes over time. The scene and music industry that I witnessed at UCLA in the late 80s has changed significantly, with possibly significant consequences for the functionality and vitality of college music scenes and, separately, urban music scenes. For instance:

The subsequent rise of hip hop and most recently EDM have changed the format and performative practices associated with being a musician. The ‘band’ is no longer the normative performing unit, and with it may have gone certain dynamics (jamming, replacing musicians, etc.) that the college music scene once supported.

Social media has ascended as a platform for discovering music, promoting musicians’ careers and advertising music events at the same time that traditional media (including free print periodicals like the alternative weekly, long the media backbone of urban music and nightlife scenes) have declined.

Higher education is on the cusp of significant changes to the composition of student bodies. In the U.S. colleges and universities have just about graduated the last of the “baby boom echo” (i.e., children of the largest demographic bulge in recent history). First-generation college students are increasingly the biggest source of growth in the composition of colleges. And in the U.S. and elsewhere, cutbacks in public support for public universities and colleges have led tuitions to rise dramatically in recent years. All of these changes threaten the affluence that have long shaped the student life, musical expressions, and youth revolts that come from colleges and universities — in terms of students’ socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as the quality of education and student services that institutions provide.

***************

Reader comments are very welcome! If you have questions or comments about this research framework — if you’re a student from Vassar, UCLA, or any other institution who remembers your college music scene — I invite your responses below.