Since we’re talking about Legs McNeil and Gilliam McCain’s Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk, one of the most colorful quotes in a book chock full of them comes from Peter Jordan, the oft-forgotten replacement for bassist Arthur Kane in the New York Dolls. Jordan describes the 1971-74 milieu in which Kane fell in Connie Gripp (who later went on to greater notoriety as Dee Dee Ramone’s girlfriend and inspiration for “Glad To See You Go”):

Arthur had a thing for tall girls. He always found these fucking enormous fucking tall girls, and the nuttier the better. He was very tall himself, maybe six foot two, and he liked to walk around at night. He’d roam through Times Square at four in the morning—he just loved roaming around the street—where he’d meet these enormous women. He had a knack for it.

Arthur came up with a tremendous succession of Amazons. It was incredible. I couldn’t believe that there was so many spaced-out fucking chicks with dyed hair and torn black stockings in every city in the United States.Where did they come from? A million of them—all enormous and with similar characteristics—all about six foot one, would drink fucking whiskey out of the bottle, and be the kind of girls who would have a broken heel on their shoe. And Arthur would find them everywhere.

Connie was one of them. She was pretty big—big butt, big tits, big laugh. She was hooking at that point, so Connie was the kind of girl who’d carry a knife, because she was peddling her ass and probably need one for protection. Also, she and Arthur were not the type of people to have a kitchen. So she didn’t go to the fucking kitchen and get a knife out of the goddamn drawer—she had to have a fucking knife in her bag. [pp. 147-8]

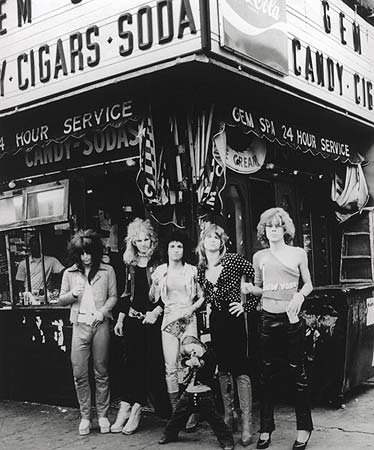

Jordan describes a way of life for denizens of an inner-city zone of vice that, in some respects, could have been ripped from the pages of a Chicago School ethnography circa 1930. The imagery and symbolism are updated to the pre-punk 70s: a low-budget androgyny of used clothing and stringy long hair for the men, unironic torn black stockings for the women. However, the portrait of personally disorganized individuals leading deviant lives in socially disorganized neighborhoods is very much the same. And, to borrow from contemporary ethnographer (and Chicago School devotee) Mitchell Duneier, the Bowery and the Lower East Side provide a “sustaining habitat” of clubs and bars, drug dealers and shooting galleries, thrift stores (not today’s vintage clothing boutiques) and low-rent/no-rent apartments, and a backdrop of urban crime and shocking violence that provides an uneasy shelter from mainstream surveillance.

If I can use just a little bit more sociological jargon, the characters that populatePlease Kill Me are very much failures of class reproduction. Hailing from working-class and lower-middle-class families at the onset of a bleak post-industrial transition, they seem to have no place to go but down—that is, downtown NYC, where they strike up marginal livings as junkies and prostitutes. (The substantial coverage of female groupies and scenesters in Please Kill Me, more extensive and less sentimental than in most other rock books, should be read in this way.) Junkies, prostitutes, rock musicians—specifically, rock musicians seeking an uncommon alternative to the technically proficient stadium rock of the day—all of these vocations consign them to the bottom of the social hierarchy. It’s no coincidence “punk” has similar status connotations in prison slang. Of course, the final destination for these individuals is an early grave, as the lurid body count in Please Kill Meattests.

This view of NYC’s rock underground further informs the remarkable contrast with today’s indie-rock enclaves that I discussed in the last post. The stringy hair, drug habits and recycled clothes can still be seen in the Williamsburgs of today. However, they now signpost an increasingly organized (if still long-shot) route to musical recognition and economic success—blogger adulation, end-of-year “best of” lists, magazine covers, licensing and film soundtrack deals, a shout-out by Jay-Z— that was unimaginable in the heyday of the Dolls.

How the capitalist consolidation of the urban underground came to pass is the subject of a vibrant academic debate around what could be called (with irony, of course) hipster studies. Unlike the mainstream disdain experienced by NYC’s first generation of punk rockers, hipsters today are rewarded symbolically and (their dream) economically for the refined tastes and status distinctions they display as consumers and low-wage service workers. Urban sociologist (and—full disclosure—my good friend) Richard Lloyd gets us closer to the urban context when he emphasizes the post-Fordist neighborhood he calls neo-bohemia, where the symbolic income of hipster cachet allows the young and artful to be underpaid and overworked in and around the creative/service sectors of the global city.

I think there’s still more to say about the historical origins that I’ve emphasized in the last two posts. Bohemianism is a starting point for understanding the NYC 70s origins of punk rock that Please Kill Me documents, but for that matter so too is the world evoked by “Taxi Driver” where arty dilettantes need not apply. From this vantage point, the revalorization of musical and urban deviance over the last four decades is a shift of immense magnitude—a veritable contrast of night and day.