Deb Bucher, Head of Collection Development and Research Services

On Valentine’s Day our thoughts turn to romance. And if you love books, you might start thinking about the great romance novels you’ve read, or are embarrassed to admit you’ve read. Think what you will about that genre, it’s been around for almost two thousand years! Around the 2nd century CE several Greek long-form stories appeared that had similar themes: boy meets girl, they fall in love, they get separated by events and bad people, they have unpleasant experiences, fate brings them back together, and they live happily ever after. Translators, artists, composers, play-writes, and illustrators have all contributed to the longevity of not just this literary form, but the ancient Greek stories themselves.

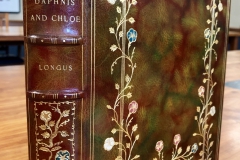

One example is the story of Daphnis and Chloe, attributed to someone named Longus, who may have lived around the year 200 CE (the jury’s still out whether or not there was someone named Longus or whether that name is just a bad reading of a manuscript!). In brief, Daphnis and Chloe grow up together on Lesbos, both adopted by shepherds. As children they don’t realize what they feel for each other is love; but as youth, they become separated, and then finally find each other again and live happily ever after. The loss of childhood innocence, the influence of nature and the merits of country living are themes that appear in the story. While the manuscript evidence for Daphnis and Chloe is slim (only two complete manuscripts survive!), scholars believe that the long-form genre was immensely popular in antiquity because so many different examples have survived, sometime only in papyrus fragments. But their last influence is also attested by a copious amount of translations from the Renaissance onward, and recent scholarship on the genre. Daphnis and Chloe was first translated into French in the sixteenth century by Jacques Amyot. His translation became a classic in its own right. You can see a beautiful 1780 edition of it at HathiTrust. The Archives and Special Collections here at Vassar also holds a copy of this edition.

A later 1890 edition of Amyot’s translation, amended by Paul Louis Courier from a more complete manuscript he discovered in 1801 at the Laurentian Library in Florence, is this beautiful edition housed at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris, France. It has artwork by Louis-Joseph-Raphaël Collin, a French painter who lived from 1850 – 1916. He was influenced by Japanese painting, which you can see in this edition. Vassar’s copy is actually an unattributed English translation published ca. 1896 also in Paris by the Société des Beaux Arts. In addition to the detailed color plates, the English edition also has historiated initials at the beginning of each chapter. The book is a wonderful example of a French livre de luxe; such books, made for collectors, were popular at this time. Mixed reviews followed it’s publication. A review in the Academy (January 16, 1897, p.73) suggests that the book “will be found alluring by a certain class of people” and that the English translation is “without charm.” In contrast, the review in the Publishers’ Circular (January 23, 1897, p.111) commends the edition as “princely.”

Our copy has special significance for us because it was a gift from Rebecca Lawrence Lowrie, class of 1913. She had no.4 of the “Edition artistique,” which was limited to seventy-five copies for England and America. It came to Vassar as part of a gift of over 3,000 items, most of which are now housed in Special Collections.