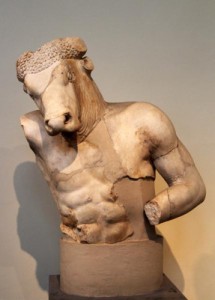

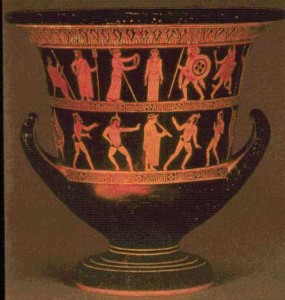

The Minotaur is a double-stranger. Born of a god-sent lust by Pasiphae for Minos’ prized bull, the Minotaur became a stranger in his own land. He was locked into the Labyrinth to hide him from the public and to hide the shame of king Minos. The half-man, half-bull would never see the light of day. However, it is not only within his home land that he is a stranger. He, and all of Crete, are strangers to the Athenians. When Minos’ son, Androgeos, won all competitions at the Panathenaic games, he was killed by jealous Athenians thinking that an Athenian should win. This jealous death led to Athenian subjugation by the Cretans who controlled the sea. As punishment, they were to give seven young men and seven virgins to Minos every nine years to be fed to the Minotaur. A stranger in a strange land, and a beast begot by a god’s revenge, the Minotaur then represents the very worst of foreign barbarism, from an Athenian perspective at least.

When Theseus finally slay the Minotaur in the third cycle of Athenian restitution to Minos, he was killing a foreigner and outcast. Even king Minos, learning of Theseus’ desire to kill the Minotaur, was not upset at the possibility of his step-son’s death. With the help of Ariadne, daughter of Minos, Theseus successfully navigated the labyrinth and more importantly successfully lefts it along with the sacrificed Athenians. He brought Ariadne as far a Naxos before leaving her alone on the island, thus leaving behind the last vestige of foreignness from his trip. As punishment for this act, Theseus inadvertently causes the suicide of his father, but still ultimately releases Athens from the shackles of a foreign Crete. It is a story worthy of Athenian praise.

But what about the Minotaur? What does he feel about the whole episode? The myths never give the half-man, half-beast a voice. In fact, a creature that is so popularly understood of for its power and ferocity takes on a completely passive role in the myth. Beginning with his placement in the labyrinth and ending with his death, the Minotaur has no say in its own life. Even his death is sometimes described of as passively; in one version Thesius says, “Would you believe it, Ariadne, the Minotaur scarcely defended himself.” The Minotaur in these myths then is little more than a symbol representing the barbarian, in the Greek context of the word, meaning someone whose language and culture were foreign.

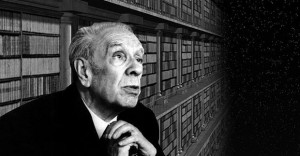

The Spanish author Jorge Luis Borges, with his short story, The House of Asteron finally provides some much needed agency to the Minotaur in his own myth. Written in the first person perspective of the Minotaur, Borges plays with the imagery of the labyrinth, the Minotaur’s own sense of self, and ideas of foreignness. In this way, Borges makes the double-stranger into the familiar and the rest of the world into foreigners. The switch is rather remarkable and quite amazing to read.

The Minotaur retains many of his barbarous traits, even as he is the principal character of the short story. For one, “I have never retained the difference between one letter and another. A certain generous impatience has not permitted that I learn to read.” Not understanding the written word, not grasping completely the language, was a sign of barbarism and further cements the foreignness that separates the House of Asteron and the rest of the Greek world. Beyond this, even his actions within his own house, the Labyrinth, bring a sense of barbarity to the character. In one game he plays, “There are roofs from which I let myself fall until I am bloody,” and in another “Like the ram about to charge, I run through the stone galleries until I fall dizzy to the floor.” These are not the games of civility, but within his own life and house, they are as natural to him, as any silly game from our own culture is to us.

Another way which Borges toys with the ideas of foreignness is within the separation between royalty and base commoners. Class politics has long been described of in terms of barbarism, with the aristocracy fulfilling the role of cultured elite and the commoners fulfilling the role of dumb barbarian worker. The Greek myth regarding Theseus and the Bull is not concerned at all with the common folk, and that in itself is rather telling. In Homer’s Iliad, the common Greek warriors are little more than cannon fodder to the Trojan Heroes and vice versa. Within The House of Asteron, this distinction is also clear. On one occasion, when the Minotaur left his Labyrinth, the common people around him either hide or lift up stones to throw at him. These actions do not bother him because “Not for nothing was my mother a queen; I cannot be confused with the populace, though my modesty might so desire.” For him, the amazement of the common people had as much to do with his own beastly appearance as it did with his royal heritage.

Of course, even Borges cannot escape the reality of the myth. In the end, Theseus murders the Minotaur and says the same line. But this time, a reason for the Minotaur’s passivity in the conflict is given. He accepts his mythic fate because he believes Theseus to be his “redeemer.” Theseus is a redeemer because he allows the Minotaur to leave his life of solitude, his life without a mate. Theseus is also a redeemer because the Minotaur hopes that his death will bring him to a “place with fewer galleries fewer doors.” This short story by Borges is a unique twist on the classic Theseus myth by placing the Minotaur into a place of agency. However, even as the Minotaur is raised up, Borges still keeps with him a sense of foreignness. Even in his own story, he is a stranger to himself and the world. He is both beast and royal. Borges then illuminates many of the same themes which are present in this Thesius myth, and in much of Greek myth in general.

Related Posts:

The Minotaur, Immortals, and the myth of Theseus

Jason and the Argonauts. And Talos.

In my AP Literature class in high school, we examined various adaptations of Greek myths throughout time, up to the 21st century. More specifically, we mainly examined literary and artistic adaptations of the myth of Icarus and Daedalus. Although this myth is a relatively short one, I was surprised by the sheer quantity of interpretations and adaptations over the years, from paintings to poems. More surprisingly, each one expanded upon a different minute detail of the original myth, turning it into a completely new and unique work of art. The adaptation I found, and still find, most striking is Edward Field’s adaptation of the myth in his poem Icarus, which describes Icarus’s life if he had survived his fall and come ashore in 20th century society (the poem can be read

In my AP Literature class in high school, we examined various adaptations of Greek myths throughout time, up to the 21st century. More specifically, we mainly examined literary and artistic adaptations of the myth of Icarus and Daedalus. Although this myth is a relatively short one, I was surprised by the sheer quantity of interpretations and adaptations over the years, from paintings to poems. More surprisingly, each one expanded upon a different minute detail of the original myth, turning it into a completely new and unique work of art. The adaptation I found, and still find, most striking is Edward Field’s adaptation of the myth in his poem Icarus, which describes Icarus’s life if he had survived his fall and come ashore in 20th century society (the poem can be read ![field[1]](http://pages.vassar.edu/grst-202-52-2015b/files/2015/05/field1.jpg)

(and therefore a god) he is offered a place on Mt. Olympus to live but he declines so he can live on earth with Meg. This is how the movie ends. Again, Disney attempts to stay somewhat true to the original story, but modifies it to a “G-rating.” In the original myth, Heracles is burned to death by a tunic accidentally laced with poison from his wife (when crossing the Euenos river, Heracles put his then wife, Diandria, on a ferry with Nessos the centaur to help her across. On the way over Nessos raped Diandria and Heracles rescued her and killed Nessos, but just before he died Nessos gave Diandria a love potion comprised of “his seed” and “his blood.” Later, on a conquest of Trachis, Heracles killed Eurytos and his sons and took Iole, his daughter and intended to sacrifice her. Diandria became afraid that Heracles would fall in love with Iole and laced his tunic with the apparent love potion from Nessos. When Heracles put on his tunic to make the sacrifice, “the hydra’s poison ate away at his flesh.” He struggled for his life: “he tried to tear off the tunic, but his flesh was torn off with it.” When Diandria learned what happened she hanged herself. Heracles then ordered his oldest son by Diandria to build a pyre for his death. There he died and became immortal.) (45).

(and therefore a god) he is offered a place on Mt. Olympus to live but he declines so he can live on earth with Meg. This is how the movie ends. Again, Disney attempts to stay somewhat true to the original story, but modifies it to a “G-rating.” In the original myth, Heracles is burned to death by a tunic accidentally laced with poison from his wife (when crossing the Euenos river, Heracles put his then wife, Diandria, on a ferry with Nessos the centaur to help her across. On the way over Nessos raped Diandria and Heracles rescued her and killed Nessos, but just before he died Nessos gave Diandria a love potion comprised of “his seed” and “his blood.” Later, on a conquest of Trachis, Heracles killed Eurytos and his sons and took Iole, his daughter and intended to sacrifice her. Diandria became afraid that Heracles would fall in love with Iole and laced his tunic with the apparent love potion from Nessos. When Heracles put on his tunic to make the sacrifice, “the hydra’s poison ate away at his flesh.” He struggled for his life: “he tried to tear off the tunic, but his flesh was torn off with it.” When Diandria learned what happened she hanged herself. Heracles then ordered his oldest son by Diandria to build a pyre for his death. There he died and became immortal.) (45).

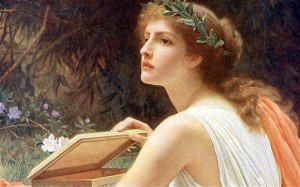

This jar is delivered to Prometeus’s brother Epimetheus and is then opened by Pandora. The opening of the jar “scattered all the miseries that spell sorrow for men. Only Hope was left there in the unbreakable container” (Hesiod 164). Therefore the opening of this box unleashes all of the pain and hurt in the world on mankind in the form of a woman. This myth also demonizes the women who walk the earth as a plague upon the men, although this patriarchal interpretation is not seen in the Lost adaptation. However the idea that Hope is something that is unattainable in the “unbreakable container” (Hesiod 164), is an important idea in Lost as well.

This jar is delivered to Prometeus’s brother Epimetheus and is then opened by Pandora. The opening of the jar “scattered all the miseries that spell sorrow for men. Only Hope was left there in the unbreakable container” (Hesiod 164). Therefore the opening of this box unleashes all of the pain and hurt in the world on mankind in the form of a woman. This myth also demonizes the women who walk the earth as a plague upon the men, although this patriarchal interpretation is not seen in the Lost adaptation. However the idea that Hope is something that is unattainable in the “unbreakable container” (Hesiod 164), is an important idea in Lost as well.