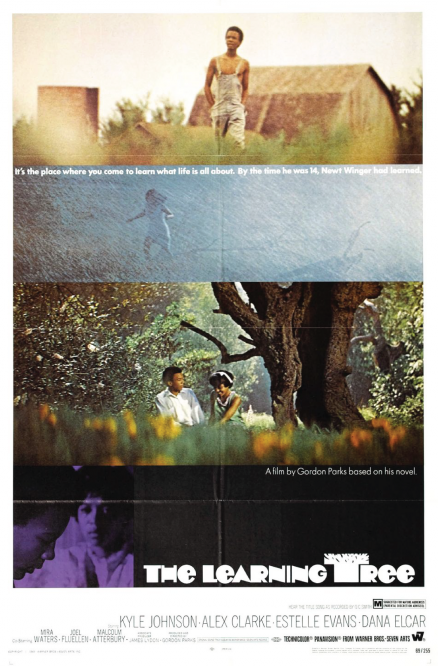

THE LEARNING TREE (1969)

In 1965, Parks was approached to turn his [semi-autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree] into a film. After several false starts, the actor and director John Cassavetes called Parks to encourage him. Cassavetes set up a meeting with a Warners Brothers executive, Kenneth Hyman who agreed that the story was compelling and that Parks should write a screenplay. The film was historic–it was the first Hollywood movie with a black director–and deeply rewarding to Parks. “For the first time during the making of a major Hollywood film, Blacks were working besides Whites behind the camera,” Parks recalled in his memoir A Hungry Heart, published in 2005. “The Learning Tree belonged to all of us, and we embraced it with a tenderness that grew as we grew. Celebrating its composition as well as its camera work, The New York Times called The Learning Tree “a photographer’s movie,” which possessed “a special visual density and an ability to hold the world together in a panoramic view.” It was the initial step in Parks’ successful film career.

In 1965, Parks was approached to turn his [semi-autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree] into a film. After several false starts, the actor and director John Cassavetes called Parks to encourage him. Cassavetes set up a meeting with a Warners Brothers executive, Kenneth Hyman who agreed that the story was compelling and that Parks should write a screenplay. The film was historic–it was the first Hollywood movie with a black director–and deeply rewarding to Parks. “For the first time during the making of a major Hollywood film, Blacks were working besides Whites behind the camera,” Parks recalled in his memoir A Hungry Heart, published in 2005. “The Learning Tree belonged to all of us, and we embraced it with a tenderness that grew as we grew. Celebrating its composition as well as its camera work, The New York Times called The Learning Tree “a photographer’s movie,” which possessed “a special visual density and an ability to hold the world together in a panoramic view.” It was the initial step in Parks’ successful film career.

SHAFT (1971)

“I had been working for almost a year on a movie called Shaft. The screenplay was based on a novel of the same name written by Ernest Tidyman. Originally planned as a run-of-the-mill detective film with a White hero, it was rewritten to feature a Black private eye, John Shaft. (…) Shaft opened on July 2, 1971, to lines around the block and audiences who stood up screaming at its conclusion. It was a particular hit with young blacks who, for the first time, had a Black hero to identify with”

“Shaft was breaking attendance records all of the country—a single theater in Chicago, the Roosevelt, took in a million dollars—when Joel came into my office, all happiness. ‘Well my friend,’ he said, ‘the smiling Cobra sure loves you. Shaft’s cleaning up. Now he wants you to go to London and show it to the press in England.’ Joel was referring to Jim Aubrey, who had just taken over the helm at MGM. I agreed to go, and Gene took a week off work and went with me.

“Shaft was breaking attendance records all of the country—a single theater in Chicago, the Roosevelt, took in a million dollars—when Joel came into my office, all happiness. ‘Well my friend,’ he said, ‘the smiling Cobra sure loves you. Shaft’s cleaning up. Now he wants you to go to London and show it to the press in England.’ Joel was referring to Jim Aubrey, who had just taken over the helm at MGM. I agreed to go, and Gene took a week off work and went with me.

There were no empty seats at the showing for the British press corps. The show went well. The audience’s reaction to the dashing Black hero was electrifying American audiences was super fine. And Isaac Hayes’s driving added to the excitement. After the film’s conclusion, I agreed t take questions. The first came from a young reporter with a shock of red hair. ‘I say there, would you please explain exactly what the word Shaft means?’

Smiling, I stuck a stiff middle finger into the air. ‘That, sir, is the most honest answer I can give you.’ The audience responded with laughter. The young man shot me another question. ‘I don’t quite get these blokes calling each other mother. Now tell me, what’s that all about?’

At a loss for an explanation, I was grateful to a woman who blurted out an answer before I could manufacture one. ‘You’ve heard of Smucker’s Jam, young man. Just snip out the first two letters and add an ‘F’ and you’ll get the message.’ Her explanation brought even more laughter, and I spent the next thirty minutes discussing the antics of the film’s dazzling hero.” (Gordon Parks, A Hungry Heart)

DIARY OF A HARLEM FAMILY (1968)