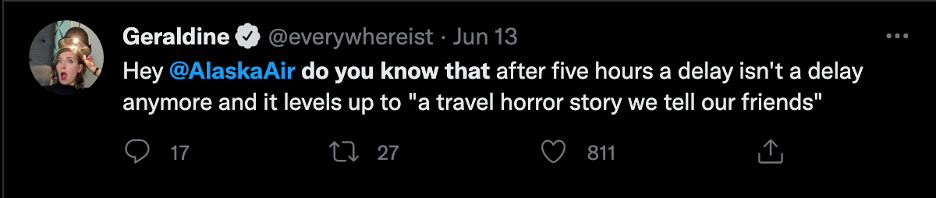

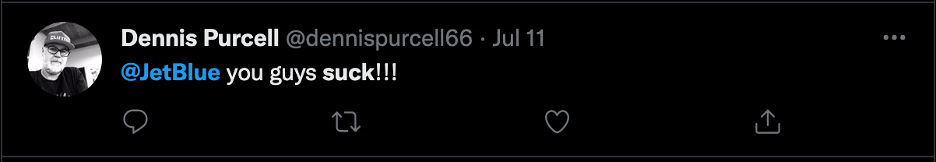

This summer, I worked with Professor Ge and Jiebei Luo, and my peer Madhav Jha on the U.S. Airline project. Specifically, we aim to discuss the product quality and consumer response using the tweets that we scraped from the Twitter API. In case of the airline industry, the number of airlines in a competitive market is low due to scale economies. Some airlines maintained their monopoly status on specific routes, and their failure to improve service quality (worsening delays) has raised nation-wise concerns and increased consumer dissatisfaction. As social media platforms (e.g., Twitter in our case) provide large amount of text data, we are able to locate tweets directed at a specific airline through mentions (@). See 1-1 below for sample tweets. Considering the short span of the program and the exploratory nature of our project, we limited our data coverage and focused on two chosen airlines, Alaska Air and JetBlue (Delta and Southwest Air in Madhav’s case), on a sample date pre-covid (Nov 12, 2019).

To retrieve historical tweets, we utilized the Twitter API, a platform that allows you to find and retrieve, engage with, or create a variety of different resources including the following: user ID, time created, text, and more. 1-2 shows an example of the tweets we pulled. Since many tweets contains URLs, digits, and other things that might disrupt the sentiment analysis, we preprocessed the tweets to trim them and make them ready for future steps.

| @JetBlue | 2019-11-12 23:12:31+00:00 | @JetBlue So your response is basically, “Suck it up, we’re giving you a flight credit later so who cares that you waste a day of your life and have to pay your own money to eat?” | 1194392560371994626 |

| @JetBlue | 2019-11-12 23:12:11+00:00 | @JetBlue We have and at 10am they had the phone and now nobody knows anything | 1194392474992676864 |

| @JetBlue | 2019-11-12 23:08:53+00:00 | .@JetBlue just sent a second email to Mosaic members explaining the fare family changes from this morning (https://t.co/zLHmhCJzzi) and their impact on the elites in the TrueBlue program. It is a good chart. I have no idea why it wasn’t the first message sent 10 hours ago. #PaxEx https://t.co/c0ycO8K5NQ | 1194391642976817153 |

| @JetBlue | 2019-11-12 23:08:08+00:00 | @JetBlue I was scheduled for 2 pm. Now scheduled for 9:15. $250 was thrown out but no guarantee that we will leave tonight. | 1194391457551044611 |

|

@JetBlue |

2019-11-12 23:07:59+00:00 | @sbbiscuit @JetBlue Interesting that’s kind of what I thought was happening. I mean I don’t know if blue plus really saved with the bags anyway but still | 1194391417549918208 |

1-2 Retrieved Tweets

The purpose of preprocessing is to get rid of any unwanted/irrelevant text elements. To conduct sentiment analysis, we used two different toolkits, TextBlob and Vander, in order to compare between results. However, computer programs have problems recognizing things like sarcasm and irony, negation, jokes, and exaggeration – things that are easy for a human to sense and identify. Failure to recognize these things can skew the results. And since some tweets contains multiple mentions, even when the overall sentiment is negative, the sentiment toward a specific airline is not necessarily negative. Therefore, after putting the texts through automated analyzing programs, we manually identified each of the tweets. See 1-3 for an example when sarcasm cannot be detected by the programs.

| Text | Preprocessed | Polarity | Sentiment_Type_TextBlob | scores | compound | Sentiment_Type_Vader | Manually |

| @JetBlue Very happy to hear. Regardless, I’ll be sure to avoid the Blue Basic fares like the plague.

|

jetblue happy hear regardless ill sure avoid blue basic fare like plague | 0.16 | POSITIVE | {‘neg’: 0.244, ‘neu’: 0.341, ‘pos’: 0.415, ‘compound’: 0.5423} | 0.5423 | POSITIVE | NEGATIVE |

1-3

Our next step would be to create visualizations to help illustrate our analysis. This summer has been really rewarding as I had zero experience in scraping data, preprocessing data, and text/sentiment analysis prior to this project. Exploring new areas is always exciting and learning about the airline industry is so relevant to our day-to-day life. Even though the research has just started, and we still have a long way to go before we draw any conclusion, being able to start from scratch and building new skills and knowledge on every step of the way is beyond precious. I would like to thank Professor Ge and Jiebei for this wonderful opportunity and experience.

Haiyi (Olivia) Xiao

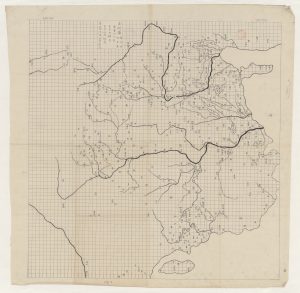

Book of Diverse Crafts (考工記), the image of the King’s city (王城圖)

Book of Diverse Crafts (考工記), the image of the King’s city (王城圖)