This summer, I worked with Professor Dozier and three other research assistants to design an introductory course for the Greek and Roman Studies Department. This introductory class will make students feel more comfortable taking higher level classes in the department by providing them with basic knowledge of Greek and Roman civilization. I felt particularly drawn to this project because I have had many people tell me that they want to take a GRST class, but don’t know where to begin. Many people feel like they would be overwhelmed in a higher level class. So, the ultimate goal of this project is to make the Greek and Roman Studies Department and its courses more accessible.

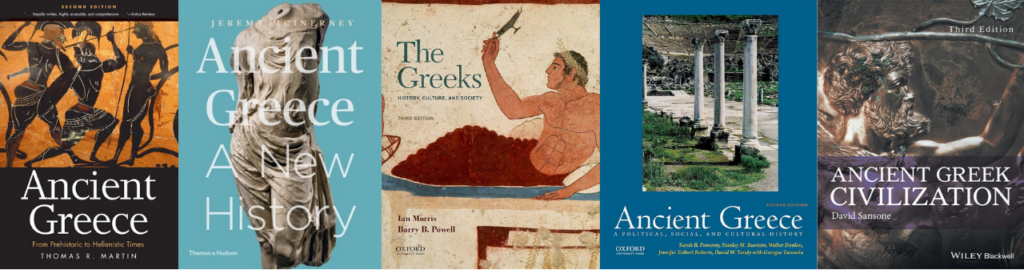

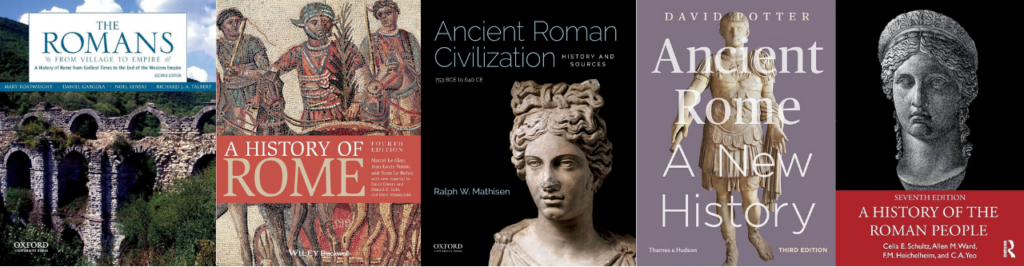

Creating this introductory class was a significant undertaking, since we hoped to give students a comprehensive overview of both Greek and Roman civilization in one semester. Professor Dozier chose to divide the class sessions into chronological history, social history, language, literature, and material culture. Our first step was to look through Greek and Roman civilization textbooks and decide which specific topics to cover during those class sessions.

We used Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times by Thomas Martin, Ancient Greece: A New History by Jeremy McInerney, The Greeks: History, Culture, and Society by Ian Morris and Barry Powell, Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History by Sarah Pomeroy, and Ancient Greek Civilization by David Sansone.

We used The Romans: From Village to Empire by Mary Boatwright, A History of Rome by Marcel Le Glay, Ancient Roman Civilization: History and Sources by Ralph Mathisen, Ancient Rome: A New History by David Potter, and A History of the Roman People by Celia Schultz and Allen Ward.

Once we had decided which topics to cover, Professor Dozier tasked us with creating an outline for each of the social history classes. Social history is a field of history that explores people’s lived reality, rather than strict political and economic history. So, our social history classes covered topics such as enslavement, religion, and leisure. We organized these outlines into questions, content, and takeaways. The questions frame the structure of each class session. The takeaways indicate what we want students to remember from the class session. The content supports the takeaways. Brainstorming and developing the questions, content, and takeaways was a very collaborative process. The other research assistants and I broke into pairs to develop them, then each pair presented their outline to the other pair and incorporated their feedback.

Once we had created outlines for each class session, we began going through the textbooks and highlighting sections that corresponded with the content we wanted to teach. At this point, Professor Dozier wanted to deliver a test lecture to determine if our process was effective. He used the outline and textbook sections we designated to develop a lecture for our first Greek chronological history day. After watching and discussing his test lecture, we realized that we needed to be more involved in the lecture-making process.

So, we began creating lecture slides and slide narratives for Professor Dozier to develop his lectures from. These lecture slides and narratives followed the same outline of questions, content, and takeaways. We synthesized information from the textbooks to create the slides and the slide narratives. The slide narratives were the most important part, because they became the basis for Professor Dozier’s lectures. We made sure to indicate where in the textbooks we got the information in the slide narratives, so that Professor Dozier could always go learn more about the material. Once we finished our slide narratives, Professor Dozier went through and left comments where he needed more clarification or more information. He also commented when he disagreed with the information, or thought we needed to go a different direction. These slide narratives and comments made the process more collaborative and ensured that we were on the same page as Professor Dozier. After Professor Dozier left these comments, we went through and incorporated his feedback to complete the slides and slide narratives.

This project had a very positive impact on me personally. First of all, it taught me how to work with and lead a team of research assistants. The four of us met over Zoom almost everyday, sometimes multiple times a day. I led these daily meetings and assigned each of us tasks in order to meet the goals Professor Dozier set for us. Leading and working with a team is a valuable skill that I will take with me far beyond this project. Designing this introductory class also gave me a better idea of what being a professor would be like and affirmed my instinct to pursue an academic career. I found the process to be challenging, but fulfilling. The most challenging part was choosing which topics to cover and narrowing down which information to include. The most fulfilling part was thinking about how to communicate the information to students in the most effective way. I am really looking forward to hearing students’ feedback in the spring!