This summer, I worked with Professor Alicia Atwood to study the long-run impacts of the measles vaccine in Mexico and explore the best ways to accessibly communicate health and economic data to broad audiences. Prior economic research has linked the measles vaccine to positive effects on schooling, employment, and income. As measles threatens its return across North America, this project presents a timely reminder of the importance of vaccination against measles. Our time was split between researching and modeling the effects of measles in Mexico and researching and implementing evidence-based approaches to data visualization.

The first half of our work began with reviewing relevant economic and health literature. From these sources and further historical documentation, we collected information to gain a clearer understanding of measles in Mexico, both before and after the introduction of the vaccine. We used these pivotal steps to inform our decisions regarding data and modeling. With strong justification, we carefully cleaned and prepared our 50 million observation dataset. Although these steps were time-consuming, they were fruitful. Once we were able to apply our model, we found significant effects on education, employment, and relationship status, all of which were consistent with previous literature.

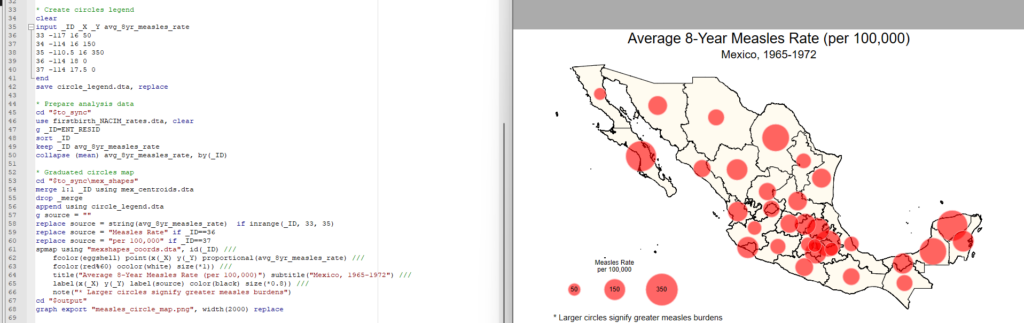

With a strong set of results established, we asked a difficult question: how can visuals help synthesize dense information into a digestible message for a broad audience? We began by revisiting previous economic and health publications to look for particularly effective and creative visuals. Then, we explored across psychology, sociology, and other sciences for visualization best practices–what graphs are most effective, which colors best tell our story, and what’s the right amount of detail for a chart. Afterwards, I spent a lot of time learning new and complex coding techniques and applying our new visualization toolkit to our data.

My time working on this project was incredibly rewarding. In an increasingly vaccine-hesitant world, I had the opportunity to contribute to the struggle against vaccine misinformation, all while improving as a researcher under Professor Atwood’s guidance. I learned so much while studying how to effectively communicate our work through visuals. Our project forced me to draw a connection between our work in an academic setting and the valuable information it has to offer the general public. For me, this unique experience drove home the crucial humanistic aspect of social science research.