THE DEBATE

The long standing popular narrative regarding immigrants and health care is that immigrants (legal and undocumented) have ready access to our nations’ health care systems and health insurance, so much so, that it has become a costly problem. However, I believe this not to be true. Healthcare and Health insurance is one of the major areas in which contemporary immigrants in the U.S. are facing heavy structural exclusion. Immigrants as a whole have significantly less access to health care and insurance in comparison to native-born citizens. The article that I have written aims at uncovering and elucidating the realities of immigrant utilization of health care and health insurance by identifying the major barriers to access for contemporary immigrants in the United States. To start, I have provided you with 3 videos that I feel highlight (to an extent) the current debate surrounding immigrants and health care usage.

In the 1st video, Dan Stein from FAIR (Federation of American Immigration Reform) points out that extending health care to undocumented immigrants comes at a cost for taxpayers. In the 2nd video, the news anchor questions the idea that undocumented immigrants should get health care by stating that there are plenty of “Americans” without health care. She also mentions firsthand accounts of border state emergency health facilities overwhelmed with undocumented immigrants coming in for treatment because they know they have the right to emergency medical service. Lastly she mentions that this is all unfair to hospitals and workers who have to deal with all of the undocumented immigrants and that they are not being paid in full by the federal government for their services. In the 3rd video, Bill O’Reilly (who is anchoring), states that the government, which is already going bankrupt, should not pay for health insurance for undocumented immigrants and refers to this idea as a “radical socialist agenda.” He also uses the word entitlement to describe health care concluding that health care is something that only citizens are entitled to and that undocumented immigrants shouldn’t even be in the U.S. in the first place but that they should be in their home countries. All of the videos center on the Emergency medical services (EMS) part of our health care system and portrays our emergency rooms to be littered and filled to the brim with undocumented immigrants. The whole debate clumps undocumented immigrants into one group and views them as one thing: unlawful leaches on the public sector. They don’t see the children, they don’t see the families, the people who have been here for many years, and those who have tried or are trying to get legal status but are being road blocked by the process and the difficulty the government creates in obtaining legal status. They also portray immigrants, especially undocumented immigrants, as fully knowledgeable about their rights as evident by their “over usage” of EMS.

In 2009, FAIR published a study titled “The Sinking Lifeboat: Uncontrolled Immigration and the U.S. Health Care System in 2009” in which they claim that the U.S. government is spending nearly 11 billion dollars on health care for illegal immigrants. In the article it’s stated that “many illegal aliens are taking advantage of legislation that requires emergency rooms to treat all patients, regardless of ability or intent to pay for the treatment. The cost of uncompensated care to taxpayers and insured patients continues to rise. Uncompensated costs have caused some hospitals to reduce staff, increase rates, cut back services, and close maternity wards and trauma centers (p.2).” Included in the costs reported by FAIR are the costs of so called “anchor babies.” According to a CNS News Article by Matt Cover titled ‘Illegal Immigrants Account for $10.7 Billion of Nation’s Health Care Costs, Data Show’, U.S. FAIR Director of Special Projects and Writer of the report, Jack Martin, stated “each anchor baby costs taxpayers an estimated $10,000 each on average. These costs are usually paid through Medicaid, the federal program designed to aid America’s poor.” And of course all of this extends out of a long standing debate regarding immigrant usage of U.S. public assistance which includes health care programs such as Medicaid, CHIP, and SCHIP. Many anti-immigrant policy makers believe that these types of programs are too generous, that they extend benefits to people who are unlawfully here, and that it’s encouraging more and more immigrants to come the U.S. According to an article titled Health Care Utilization, Family Context, and Adaptation by Felicia B. Leclere et al., “The basic concern is whether new immigrants take more from public coffers through their use of services than they contribute in taxes and economic stimulation” (p. 371). To me, the current narrative is nothing more than a misrepresentation of the realities of health care usage for immigrants in the U.S. The question that I pose is: Are immigrants, legal or undocumented, really using federal health care as much as people think? If not, why not?

THE ‘REAL’ DATA

Firstly, the numbers would suggest that immigrants as a whole are not using health care services as much as people think.

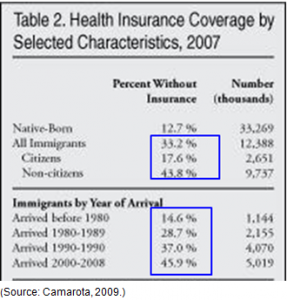

According to a March 2008 Current Population Survey (CPS) under U.S. Census Bureau conducted by Center for Immigration Studies, in 2007: 33.2% of all immigrants did not have health insurance vs. 12.7% of native-born Americans (table 1). 17.6% of legal immigrants were uninsured and 43.8% of illegal immigrants were uninsured (table 2). The number of uninsured immigrants is rising over time (Table 2).

According to the 2010 American Community Survey and 2010 Census, these numbers have held. 34% of immigrants were uninsured. 22% had public health insurance vs. 31% for U.S. born.

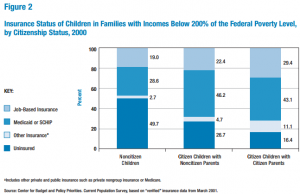

You can also see in information from Gabrielle Lessard and Leighton Ku (2003), that a greater number immigrant children or children of immigrants are uninsured. Undocumented children use much less federal health care programs in comparison to citizen children.

THE BARRIERS TO ACCESS AND USAGE

So if immigrants are not using health care and are not generally insured then what are the reasons for this? I have simplified the major barriers to access for contemporary immigrants to what I call ‘The 3 Ls’. They are Legislation, Legal Status, and Language.

1. Legislation – PRWORA (Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act)

- This 1996 reform law significantly reduced eligibility to public health care and insurance programs for immigrants (Derose, p. 1261)

- Provisions include: 5-year waiting period (after obtaining legal status) for immigrants before being eligible for Medicaid/TANF, states retain the ability to remove the 5-year waiting period and cover lawfully residing immigrants themselves, and Undocumented immigrants are completely ineligible for all services under PRWORA. (Derose, p. 1259).

Public charge – government retains the right to deem a person seeking admission to the U.S. or permanent residence (green card) as “inadmissible” if they are thought to become primarily dependent on government funded services including long term institutional care.

2. Legal Status – Undocumented immigrants are much less likely to use health care and are more likely to be uninsured than legal immigrants. Undocumented Latino/as, for example, obtain fewer ambulatory physician visits than U.S. born Latino/as (Berk et al., 2000).

3. Language – Immigrants with low English proficiency have much harder times accessing and obtaining health insurance and health care. Adults with limited English proficiency and their children are much less likely to have insurance and a usual source of care, have fewer physician visits, and receive less preventive care than those who only speak English (Derose et al., p. 1260).

As a result of legislation and legal status, all immigrants are discouraged from using publicly funded health care services because of fear deportation or fear putting their chances of citizenship in jeopardy if they seek health care (Derose, p.1263) Even children of immigrants are less likely to use health care (Lessard and Ku, p.101). Often this is the result of their parents’ language and legal status. Immigrant parents are often uninformed about eligibility and rules because of language and because of their legal status they fear being reported to INS. (p.101, 104). Due to language barriers, immigrants have higher feelings marginalization and discrimination, which further turns immigrants away from the health care system (Derose, p.1262) as well as more misdiagnosis, mistreatment, and poor medical care (Lessard and Ku, p. 108)

WHAT NEEDS TO CHANGE?

There are several things we could be doing to improve the health care situation for immigrants. These include, federal level action and reform including the revision of PRWORA, expand opportunities for legal residency and citizenship, lower health insurance costs, employer mandated health insurance, developing more qualified bilingual staffs that incorporate members of the community by creating more opportunities for them, extending eligibility to parents of eligible children (which will enhance access and usage), better enforcement of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act which requires providers who received Medicaid/SCHIP to provide those who speak limited English meaningful access (Lessard and Ku, p.111), and increase funding for community health centers and outreach organizations. Lessard and Ku express the same sentiment that culturally appropriate, community based outreach is important for having immigrant, especially children, involved in the health care system (p.110).

Read about a woman bringing local health care to immigrants in Oakland (http://www.contracostatimes.com/my-town/ci_26909381/oakland-woman-brings-health-care-and-sense-home)

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT?

The health care status of many immigrants, as a result of lack of access, is deteriorating which is why I believe this is an important issue. Immigrants are at a higher risk for poor physical and psychological health because of the barriers they face and given how the composition of our nation is changing and we’re becoming more and more populated with immigrants, we need to help the majority of the people beginning to build our nation. In “The Health Status and Risk Behaviors of Adolescents in Immigrant Families” by Kathleen Mullan Harris (1999), Harris examines the health status of immigrant children as an indicator of assimilation and acculturation and finds that for many immigrant children, the longer they are exposed to U.S. culture and institutions, the more they develop the health status and health risks associated with behavioral norms in the U.S. (p.311) She also points out that socioeconomic and legal status plays a role in bad health for immigrant children. This is also echoed in a Singh and Miller piece (2004) which states that the risks of disability and chronic disease morbidity during 1992-1995 among immigrants of various ethnic backgrounds increased with increasing duration of residence in the United States” (p.115) Ultimately at the moment, it appears that the U.S. government is forging a health care system in which contemporary immigrants have minimal access and structural inclusion and that doesn’t seem very “American” to me.  References

References

Berk, Marc L., Claudia L. Schur, Leo R. Chavez, and Martin Frankel. 2000. “Health care use among undocumented Latino immigrants.” Health Affairs 19(4): 51-64.

Camarota, Steven A. 2007. “Immigrants in the United States, 2007: A Profile of America’s Foreign-Born Population.” Center for Immigration Studies, Washington, D.C.

Derose, Kathryn Pitkin, José J. Escarce, and Nicole Lurie. 2007. “Immigrants And Health Care: Sources Of Vulnerability.” Health Affairs 26(5): 1258-1268.

Harris, K.M. 1999. “The Health Status and Risk Behaviors of Adolescents in Immigrant Families.” Pp. 286-315 in Children of Immigrants: Health, Adjustment, and Public Assistance, edited by D.J. Hernandez. Washington, DC: National Academiy Press.

Leclere, Felicia B., Leif Jensen, and Anne E. Biddlecom. 1994. “Health Care Utilization, Family Context, and Adaptation Among Immigrants to the United States.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35(4): 370-384.

Lessard, G. and Leighton Ku. 2003. Gaps in Coverage for Children in Immigrant Families. Health Insurance for Children 13(1): 101-115.

Ruark, Eric and Jack Martin. 2009. “The Sinking Lifeboat: Uncontrolled Immigration and the U.S. Health Care System in 2009.” Federation for American Immigration Reform, Washington, D.C.

Singh, G.K. and Barry A. Miller. 2004. Health, Life Expectancy, and Mortality Patterns Among Immigrant Populations in the United States. Canadian Journal of Public Health 95(3): I14-121.