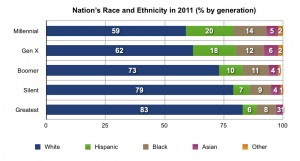

Despite being one of the most important socialization institutions for youth in America, schools seem to fail at fostering appreciation and acceptance of differences present in students. Within the last decade, minority groups have surpassed the American mainstream, which has classically been considered to be American-born, White middle class, in the K-12 age bracket of the population. Currently, minority students make up more than half of the school-aged population (Calderón, Slavin and Sánchez 2011) and approximately twenty percent of that youth population is immigrants or children of immigrants (Pumariega and Rothe 2010.) Out of the immigrant and children of immigrant, a majority of these students are Hispanic, specifically of Mexican decent, and of Asian decent (Peguero 2009).

With this influx of diversity in schools, institutional change has been slow to provide the appropriate care and support for these students to feel safe as they learn and socialize, which manifests itself in the typically lower performance of immigrant youth (Crosnoe and López 2011.) As a result, peer-peer bullying in schools persists as a major problem for immigrant and children of immigrant youth. Bullying that occurs to this particular group students differs from other types of bullying as these students are targeted based on their perceived ethnicity and their lack of power in comparison to their peers caused by differing appearances, language and cultural norms in compared to what is considered the American mainstream (Scherr and Larson 2010.) It is important to keep in mind, however, that ethnicity and race are two separate factors that could cause bullying of students. Ethnicity tends to be “chosen or assigned,” while race is defined as the categories created by the “racial categories or hierarchies [that are] reinforced through micro-level interactions” (Kao, Vaquera and Goyette 2013: 108).

Though bullying does not seem to connect to school in an academic sense, bullying in schools causes a host of negative physiological effects that alter how a student will perform in school and the opinions they will form about schools and other American institutions. Many existing school policies, like the structure of English Language Learning (ELL) classes as being subtractive in regards to viewing foreign languages as a hindrance for immigrant students (Calderón, Slavin and Sánchez 2011), and societal norms and stereotypes make schools unsafe for immigrant and children of immigrant youth. This problem is rooted in general society, as opposed to being a direct result of schooling, which makes finding appropriate ways to reduce bullying in schools or handling an immigrant or child of immigrant bullying situation complex.

In order to better understand the bullying of immigrant youth, it is important to ask the following questions to grasp a more complete understanding of the problem.

- Who is being victimized?

- Who are executing these acts?

- What acts are being committed toward immigrant and children of immigrant students?

- Why are these victims being bullied?

- What can be done to help alleviate this problem?

Who is being victimized?

The students that are targeted for this type of bullying differ from the American mainstream in cultural practices, ethnicity and occasionally, race (Scherr and Larson 2010:225). Many times, these characteristics are perceived by the perpetrators based on factors like spoken language or English-speaking abilities and race, which make it difficult to clearly define the precise group that is being bullied. In order to account for this, we will focus on the bullying of students who themselves are immigrants and students who are children of immigrants. These students are most likely to have perceivable differences from the American mainstream that their peers can pick up and ostracize them for.

Who are executing these acts?

White students, minority students and fellow immigrant students themselves perpetrate bullying of immigrant students (Scherr and Larson 2010: 227). These acts of bullying usually appear in the form of micro-aggressions and preference for their own ethnic or racial group in elementary school and progress into more outwardly pointed types of teasing and occasionally, violence (Scherr and Larson 2010: 231).

What acts are being committed toward immigrant and children of immigrant students?

Bullying takes shape in classrooms in the form of micro-aggressions or physically violent acts that solidify racial and ethnic hierarchical structure and the racial and ethnic stereotypes. Friend choice, the formations of friend groups or cliques and their physical locations within schools and taunting are common forms that micro-aggressions that students use to point out differences in students and their or their family’s immigrant status. Blunter forms of bullying include causing physical harm towards someone through hitting, kicking, fighting or other actions target at the student’s body (Peguero 2009). These incidents can many times be classified as bias incidents as they attack a student for their backgrounds, which are not variable to change, but are not treated as such by school administration (Bridging Refugee Youth& Children’s Services 2014).

Why are these victims being bullied?

As previously mentioned, immigrant and children of immigrant students that are being bullied are targeted because of their ethnic and racial differences in comparison to the mainstream. These ideals, however, stem from society itself and how schools choose to perpetuate these ideals to their staff and students. Two major classes of immigrant populations in schools currently are Hispanic youth and students of Asian descent. These two groups are treated very differently, however, due to the prevalent stereotypes that exist about them in society.

Despite the fact that students who are within the first generation, meaning they were born in their home country and moved to America, are high achieving no matter the country of origin, students of Hispanic origin are perceived as being less capable and intelligent than their peers (Kao, Grace and Goyette 2013). This stereotype is perpetuated through the school structure via teacher opinions and expectations of students and the negative association students and teachers have with students who must participate in ELL programs. These programs tend to physically isolate students from their peers as well as instill the idea that knowing a language other than English is not an asset, despite the fact that foreign languages are usually a requirement to attend college (Calderón, Slavin and Sánchez 2011.) This also occurs to immigrant students who fall into an existing group in America that is mistreated and stereotyped, like Black students. When Black immigrants come to the United States, they grouped together with native-born Black Americans and are attributed as being lower achieving and classroom instigators, as that is the common narrative perpetuated in society (Kao, Grace and Goyette 2013).

Contrary to the stock stories about Hispanic immigrant students, students of Asian descent are stereotyped to be high achieving. This creates a perceived competition between these immigrant students and others and a higher pressure to for students of Asian decent to either fulfill stereotypes or actively disassociate with them (Kao, Grace and Goyette 2013). ). The added stress for both of these ethnic groups to fit in with their peers in order to feel safe and respected at school in addition to trying to break out of the stereotypes put on an exorbitant amount of stress of immigrant and children of immigrant students before even being bullied. The act of bullying students employs the multiple risk model, where many negative factors compact and create a larger, detrimental effect on these students. Outcomes of these types of bullying can be lower school performance, mental health issues and additionally bullying or aggression (Yu et al 2003).

What can be done about to help alleviate this problem?

The bullying of immigrant and children of immigrant children in schools is generated by a lack of understanding and acceptance for differences and can be combated in multiple ways. On a societal level, the removal these harmful stigmas and stereotypes will alleviate some of the pressure felt by immigrant students to fit into a particular mold. Within schools, however, strong relationships teacher or other staff members and immigrant students has been shown to have positive effects on breaking these stereotypes of students held by teachers and other students as more individualized understanding of the students needs and strengths are uncovered (Peguero and Bondy 2011).

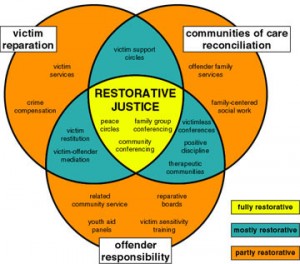

Treating these bullying incidents as bias incidents is another way in which schools can work to decrease bullying. This puts more importance and stress on the reasoning behind the bullying by recognizing that the student is being attacked for their ethnicity and race- something they cannot change about themselves. Restorative justice approaches to dealing with bullying are frequently successful. This method stresses that an understanding of why the act was harmful and holding the perpetrator accountable for their actions. (BRYCS 2014).

Engaging students in more culturally diverse lessons will also help broaden the opinions of students and help them understand their peers (Warikoo and Carter 2009). Along the lines of looking at these students for their individual assets specific to their cultures and backgrounds, counseling and advice given to these students should promote these characteristics, like utilizing strong family connections, bilingualism and code switching abilities when helping students adjust in schools. By promoting these different cultural assets, bullied students feel increased levels of confidence and their peers are able to see that these characteristics, while they are different, are positive (Villalba 2007).

References Cited

Bridging Refugee Youth & Children’s Services. 2014. Refugee Children in U.S. Schools: A Toolkit for Teachers and School Personnel (Grant No. 90 RB 0022). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health Services.

Calderón, Margarita, Robert Slavin, and Marta Sánchez. 2011. “Effective Instruction for English Learners.” The Future of Children 21(1): 103-127.

Crosnoe, Robert and Ruth N. López Turley. 2011. “K-12 Educational Outcomes of Immigrant Youth.” The Future of Children 21(1):129-152.

Kao, Grace, Elizabeth Vaquera and Kimberly Goyette. 2013. Education and Immigration. Malden, MA: Policy Press.

Keene, Douglas L. and Rita R. Handrich. 2012. “Talkin’ ‘bout our Generation: Are We Who We Wanted to Be?” The Jury Expert. 24(1): 1-18.

National Center for Education Statistics 2014. Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Peguero, Anthony A. and Jennifer M. Bondy. 2011. “Immigration and Students’ Relationship with Teachers.” Education and Urban Society 43(2): 165-183.

Peguero, Anthony A. 2009. “Victimizing the Children of Immigrants: Latino and Asian American Student Victimization/” Youth & Society 41(2): 186-208.

Pumariega, Andres J. and Eugenio Rothe. 2010. “Leaving No Children or Families Outside: The Challenges of Immigration.” American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 80(4): 505- 515.

Scherr, Tracey, G. and Jim Larson. 2010 “Bullying Dynamics Associated with Race, Ethnicity, and Immigration Status.” Pp. 223-234 in Handbook of Bullying in Schools, edited by S.R. Jimerson, S.M. Swearer and D.L. Espelage. New York: Routledge.

Wachtel, Ted and Paul McCold. 2003. “In Pursuit of Paradigm: A Theory of Restorative Justice” International Insititute for Restorative Practices. 1-3.

Warikoo, Natasha and Prudence Carter. 2009. Cultural Explanations for Racial Ethnic Stratification in Academic Achievement: A Call for a New and Improved Theory. Review of Educational Research. 79(1): 366-394.

Villalba, Jose A. Jr. 2007. “Culture-specific Assets to consider when counseling Latina/o Children and Adolescents.” Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 35(1): 15-25.

Yu, Stella M., Zhihian J. Huang, Renee H. Schwalberg, Mary Overpeck and Michael D. Kogan. 2003. “Acculturation and the health and well-being of U.S. Immigrant Adolescents.” Journal of Adolescent Health 33(9): 479-488.