The US has long prided itself on its long history of immigration, and immigrants’ hard work and contributions to US society. However, the image of immigrants and the idea of immigration is often one in an urban setting, probably because immigrants did tend to initially settle in central cites, and later move out into the suburban and rural areas of the country.

However, recently immigrant settlement pattern have begun to shift towards initial settlement in the suburbs and into regions without long histories of immigrant populations, or at least in the twentieth century (For a cool interactive, color-coded map by the New York Times demonstrating these changes in settlement, click here). With the changing patterns in settlement patterns, immigrant communities are finding new ways to maintain an ethnic identity that are both similar to and different from the old ethnic enclave model in new, more suburban settings. In addition, their host communities also play a part in shaping how they integrate structurally through actively promoting the various forms of diversity they might bring, or by actively excluding them from mainstream local life through both formal and informal methods.

What, exactly, are the new immigrant settlement trends?

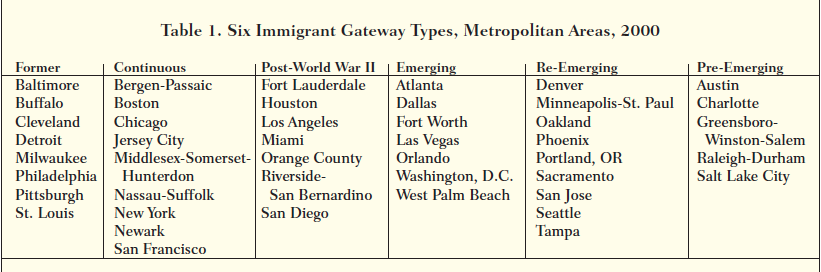

A majority of immigrants now live in the suburbs, and are increasingly moving into new regions of the US that did not previously have high populations of immigrants. Using census data from through the year 2000, immigration researcher Audrey Singer (2004) demonstrates that of those that live in metropolitan areas, more immigrants live in suburban areas compared to those who live in the central cities (10). She goes on to elaborate on and categorize the types of “immigrant gateways,” sorting US metropolitan areas that are former, continuing, or emerging gateways. Of the three types of emerging gateways (metropolitan areas that saw large increases in immigrant populations and/or growth rates between 1980 and 2000), a majority is in the southern Sunbelt region of the US (Singer 2004:5,7).

Source: Table 1, Singer, 2004.

So what? Why do we care that immigrants are moving?

This new initial immigrant settlement outside of cities and the stereotypical ethnic enclaves is leading scholars to question the theory of spacial assimilation. According to classical theory of assimilation, as outlined by Warner and Srole (1945), freedom in residential choice and movement out of ethnic enclaves in central cities into more “American” areas is reflective of assimilation into the American mainstream and immigrants’ loss of ethnic identity (288). Even as recently as 2003, in their book on assimilation in the contemporary US, Richard Alba and Victor Nee found this theory of movement into the suburbs reflecting increased assimilation in terms of upward socioeconomic mobility still holds true for the most part as of the 1990s, when their data was collected, although they do wonder what about the implications of these new trends in the assimilation of future generations (254-6). Only relatively recently have researchers been able to look into the effects of the emerging immigrant settlement trends and any implications for the incorporation and assimilation of current and future immigrants.

Happening Now: How are immigrants maintaining a sense of community and ethnic identity?

Despite a lack of the urban ethnic enclave that was so important to the incorporation of generations of immigrants, both pre- and post-1965 waves of immigration (in 1965, US immigration restrictions were loosened, allowing for a “second wave” of immigration), immigrants settling outside of central cities are still maintaining their ethnic communities, sometimes in ways very similar to the urban enclaves (Alba and Nee 2003:88; Portes and Rumbaut 2001:303-304). An example of the fusion of suburban and the ethnic enclave-like community can be seen in Eden Center, a Vietnamese shopping center in Northern Virginia, which serves as a community center where Vietnamese-Americans gather to socialize, shop, and eat (Wood 2006:36). It is a fairly American plaza-mall, with a large parking lot in front, and many stalls and shops, but with a Vietnamese social and economic environment, comparable sociocultural environments in urban ethnic enclaves, which provides a sense of cultural and territorial familiarity and a symbol of Vietnamese identity for Vietnamese and Vietnamese-Americans in this US suburb (Wood 2006:37-8).

Eden Center (Photo by kimnt, on Google Maps)

For Latinos in the greater metropolitan Phoenix, Arizona, in addition to Latino-oriented businesses as places used to maintain cultural identities and ties like the Vietnamese in Virginia. In addition, there are also clubes de oriundos, or “hometown associations,” which connect Latino immigrants in Phoenix from the same hometown or region to each other and to the people of the town or region they left behind, allowing for transnational community ties to prosper (Oberle and Wei 2008: 98-9, Fouron and Glick-Schiller 2002:169). Here, Latinos are seeking out co-ethnic community and socialization, particularly those from the same region, in the absence of it happening unintentionally on a daily basis in a high-density urban ethnic enclave.

Happening Now: How are local governments and communities reacting to their demographic changes?

As can be expected in the midst of changes in people’s hometowns and communities, there are a wide variety of reactions to the influx of immigrants to areas and towns with little history of immigration.

Some towns actively promote, advertise, and celebrate the various cultures of their newest residents. In Plano, Texas, a small city in the Dallas-Fort Worth metropolis, the city pursues very inclusionary agenda, including sponsoring an annual international festival, allowing all residents to communally celebrate each other’s cultures and expanding the library services to reflect the changing population, including books and events in languages other than English, and on topics such as computer skills and the citizenship naturalization process (Brettell 74-7).

Some of Plano’s International Festival Participants (Photo by Frozina Goussak)

Other places have been more hostile to the influx of immigrants, especially if they are perceived to be a drain on social services or a threat to way or quality of life. Emporia, Kansas recently in the mid-2000s of Somali refugees (Kulcsar and Iaroi 2013:223). These relatively recent and dramatic demographic changes had the town scrambling, with residents’ reactions continually returning to fear abut changes and job availability, immigrants relying on government assistance and refusal to learn English or adopt American customs (Kulcsar and Iaroi 2013:236-7). In Georgia state, a rather exclusionary policy was formalized in the Senate Bill 529 of 2006, which authorized aggressive policing of immigrants—and those perceived to be immigrants—in an effort to address illegal immigration in the state (Odem 2008:131).

With these new patterns and demographic shifts, many native-born Americans are understandably worried about possible changes to their way of life and home. However, immigrants are, always have been, and will continue to be an important part of American society. Americans, regardless of national origin, immigrant status, race, or place of residency, need to recognize their importance, and make sure they are welcomed and included, structurally and socially in US life, despite potential anxieties about their incorporation. Let’s make celebration, not apprehension, the norm in US immigration discussions.

References:

Alba, Richard and Victor Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Brettell, Caroline B. 2008. “’Big D’: Incorporating New Immigrants in a Sunbelt Metropolis.” Pp. 53-86 in Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America. Edited by Audrey Singer, Susan W. Hardwick, and Caroline B. Brettell. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institutional Press.

Fouron, Georges E. and Nina Glick-Schiller. 2002. The Generation of Identity: Redefining the Second Generation Within a Transnational Social Field. (pp. 168-208)

Kulcsar, Laszlo J. and Albert Iaroi. 2013. “Immigrant Integration and the Changing Public Discourse: The Case of Emporia, Kansas.” Pp. 222-248 in Latin American Migration to the Heartland: Changing Social Landscapes in Middle America. Edited by Linda Allegro and Andrew Grant Wood. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Oberle, Alex and Wei Li. 2008. “Diverging Trajectories: Asian and Latino Immigration in Metropolitan Phoenix.” Pp. 87-104 in Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America. Edited by Audrey Singer, Susan W. Hardwick, and Caroline B. Brettell. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institutional Press.

Odem, Mary E. 2008. “Unsettled in the Suburbs: Latino Immigration and Ethnic Diversity in Metro Atlanta.” Pp. 105-136 in Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America. Edited by Audrey Singer, Susan W. Hardwick, and Caroline B. Brettell. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institutional Press.

Portes, Alejandro and Ruben G. Rumbaut. 2001. “Conclusion—The Forging of a New America: Lessons for Theory and Policy.” Pp. 301-318 in Ethnicities: Children of Immigrants in America. Edited Ruben G. Rumbaut and Alejandro Portes. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Singer, Audrey. 2004. “The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways.” Living Cities Census Series. Brookings Institution, Washington D.C.

Warner, Lloyd and Leo Srole.1945. Excerpt from The Social Systems of American Ethnic Groups. P. 283-296. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wood, Joseph. 2006. “Making America at Eden Center.” Pp. 23-40 in From Urban Enclave to Ethnic Suburb: New Asian Communities in Pacific Rim Countries. Edited by Wei Li. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.