Tepe Hissar

May 9, 2017

Alternate spellings: Tappa Hesār, Tapeh Hesar, Tappeh Hesar, Tappe Hesar

The site of Tepe Hissar was an important location in Central Asia during the Late Neolithic time period and leading up to the Iron Age. It is located in northeastern Iran, just south of the city of Damghan. It experienced three major periods of inhabitation, and is known for its burnished grey pottery and lapis lazuli bead-working.

The first excavation of Tepe Hissar was led by Erich F. Schmidt in 1931-1932 on behalf of University of Pennsylvania Museum. There were two seasons of excavation, the first from July to mid-November in 1931 and the second from May through November in 1932. While Schmidt’s main objective in these excavations was to uncover more information about Tepe Hissar, he was also preoccupied with having to provide artifacts for the sponsoring museums in Pennsylvania and Tehran, which would be split 50/50 as according to the revised Iranian Antiquities Law. He often accredited signs of cultural change to the invasion of foreign ethnic groups, as was typical of anthropologists during this time period. There was another excavation organized in 1976 by the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Turin University, and the Iran Center for Archaeological Research (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Schmidt divided the stratigraphy of the site into three parts: Hissar I, Hissar II, and Hissar III. The starting point of Hissar I is slightly unclear, but is recognized as having occurred after 5,000 BCE. The second period, Hissar II, is dated from the 4th millennium to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE. It is believed that Hissar III ended before the Iron Age, and most sources place the end of occupation at Tepe Hissar at sometime in the first half of the second millennium BCE (Voigt and Dyson, 1992). This is evidenced by the absence of iron in Hissar III (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016). While Schmidt relied heavily on ceramic findings in dating the various periods of human occupation at Tepe Hissar, more modern techniques, such as radiocarbon dating, have provided more accurate boundaries between the periods. For example, radiocarbon samples have provided a range of between 2800 to 2400 BCE for the Hissar III time period (Bovington, 1974). The dates of these time periods have also been largely inferred through looking at other sites in the area, which has resulted in some confusion but has also been fairly effective. For example, many of the metal and stone artifacts found resemble those of the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia, while others appear to belong more to the Akkadian or Ur III periods. This means that the objects date between 2500 BCE to 2100 BCE (Gordon, 1951).

Small amounts of calcite and steatite found with artifacts signifying various stages of bead-making. Additionally, there were bits of lapis and flint blades and drills found throughout the site, indicating that the manipulation of precious stones was a viable industry. An abundance of small clay and alabaster animals was also found, which Schmidt attributed to both spiritual and utilitarian uses. Clay “stamp seals” with geometric designs were also uncovered, but there is a lack of evidence of imprints of the stamps, leading anthropologists to believe that they could be small ornaments or buttons instead. The lack of evidence could also be explained by how hastily the excavators were working. However, one “stamp seal” of interest depicted two human figures, an ibex, and snakes. This incorporation of human figures into geometric and animal designs was very unusual for the Hissar I time period (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Figure 1: Three alabaster animal figures found in grave “Warrior 2″(Penn Museum, object nos. 33-15-526, 33-15-525, 33-15-524) (Photo by Jason Francisco)

The burials at Tepe Hissar were mostly found on the Main Mound and North Flat areas. Three main types of burials were identified. Most of the bodies were buried in the “pit” style, or they were wrapped in wool clothes and interred in a pit. “Cist graves” were burials within enclosures, and the objects buried with the dead are often indicative of more wealth. There were also “communal chamber burials,” ranging from two to 28 individuals. Both the “cist graves” and the “communal chamber burials” are much more uncommon than the “pit” graves. Schmidt also identified four especially wealthy graves that were discovered, which he labeled “warrior 1,” “dancer,” “little girl,” and “priest.” These individuals were buried with metal weapons, agricultural tools, and domestic utensils, including stone and copper seals, a “fan”/mirror, small clay animal sculptures, and copper, silver, and alabaster female figurines (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Figure 2: GIS map of Tepe Hissar, showing the burials concentrated in the Main Mound and North Flat areas (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016; Kılınç Ünlü and Torres, 2010)

The people who occupied Tepe Hissar are often referred to as belonging to the Hissar, Gurgan, or Eastern Grey Ware culture. They are believed to have assisted communication and contact throughout Iran and Mesopotamia, especially towards the end of the Bronze Age (Bovington, 1974). According to The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, the Hissar culture “represents a culture, archaic in appearance, of tribes of the foothills and mountain valleys that evidently developed at the same time as the more developed, settled farming cultures in other parts of Middle Asia.” This definition reveals ideological biases related to the supposed “underdeveloped” nature of Central Asian cultures in comparison to more northern settlements. In looking at archaeological evidence, the economy of Tepe Hissar was based on agriculture. Plant remains indicate “an agricultural system based on cereals [glume and free-threshing wheats, naked and hulled barley] and the utilization of local fruit [olive, grapevine] plant resources” (Costantini and Dyson, p. 66). Some of the clay figures were cattle and sheep, indicating herding activities (Mashkour, 1996).

The site of Tepe Hissar is clearly visible on Google Earth. The coordinates are 36°09’16.13″ N 54°22’59.30″E and the elevation is approximately 3,679 feet. The site is cut in half by what seems to be a paved road, and half of the site is enclosed within another curving road.

Works Cited

Bovington, C. H., Jr., R. H., Mahdavi, A., & Masoumi, R. (1974). The Radiocarbon Evidence for the Terminal Date of the Hissar IIIC Culture. Iran, 12, 195. doi:10.2307/4300513

Costantini and Robert H. Dyson, Jr., “The Ancient Agriculture of the Damghan Plain: The Archaeological Evidence from Tepe Hissar,” in Naomi F. Miller, ed., Economy and Settlement in the Near East: Analyses of Ancient Sites and Materials, MASCA, Research Papers in Science and Archaeology 7, Suppl., Philadelphia, 1990, pp. 46-68.

Gordon, D. H. (1951). The Chronology of the Third Cultural Period at Tepe Hissar. Iraq, 13(1), 40. doi:10.2307/4199538

Gürsan-Salzmann, A. (2016). The new chronology of the Bronze Age settlement of Tepe Hissar, Iran. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

M.M. Voigt and R.H. Dyson, Jr., “The Damghan/Khorasan Sequence,” in R.W. Ehrich, ed., Chronologies in Old World Archaeology, 2 vols., Chicago, 1992, I, pp. 169–74; II, pp. 127–28, 135-36.

Okladnikov, A. P. “Issledovaniia pamiatnikov kamennogo veka Tadzhikistana.” In Tr. Tadzhikskoi arkheologicheskoi ekspeditsii. vol. 3. Moscow-Leningrad, 1958.

Yaghmay Mashkour “faunal remains from Teppeh Hissar (Iran),” in Proceedings of XIII International Congress of Prehistoric and Protohistoric Sciences, Forli, Italia,September 1996 I, (3), Forli, 1998, pp. 543-51.

The Subeixi Site (& Cemeteries)

May 9, 2017

Also Known As: Su Beixi / 苏贝希 (Chinese – “Suibei”)

(Closest) Coordinates: 42.858519 N, 89.691976 E

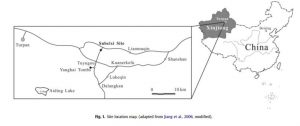

Most commonly known in its scholarship as “The Subeixi Site,” this site shares its named both with the nearby village of Subeixi (meaning “origin of water,” as the village lies in a small oasis north of Mt. Huoyan) as well as with what its referred to as the “Subeixi culture,” believe to have occupied areas in the Turpan Basin nearly 3,000 years ago (Lu & Zheng, 2003; Hirst , 2016). Though located in the Turpan Basin, Shanshan County, Xinjiang Uighur (/Uyghur) Autonomous Region of China, there is some ambiguity in texts referring to work done at the site regarding its precise location, as some merely say it lies within the Tuyugou Valley (Gong et al., 2011). With many of the accounts not providing a set of coordinates by which to easily locate the site, the description which Lu & Zheng give is:

“The site lies in the center of the Mt. Huoyan, 3 km south of the Subeixi Village. It is on an irregular terrace, which likes an isolated island, surrounded by cliffs. The terrace’s east side is lower than the west side, with uneven surface.” (Lu & Zheng, 2003)

[With several accounts saying the Subeixi site lies within the Tuyugou Valley and and/or is under the control of Tuyugou Township, Shanshan County, the closest image capable on Google Earth is of the whole Tuyugou Valley. The site is cited as being somewhere north of the valley, on the eastern-facing side of the Flaming Mountains/Mt. Huoyan. The distance from the Tuyugou Valley to the town of Shanshan is measured as approximately 42.47 km. ]

Site location map from Jiang et al. (2006) provided in several articles, yet no definitive coordinates have been cited.

The site itself contains the remains of three houses and three cemeteries, holding several large deposits of artifacts both in surface findings as well as when excavations were performed. Radiocarbon dating of items found both in the house remains and from the coffin beds within the cemetery graves dates the overall site between 500-300 BCE, further confirmed by dating performed on several of the unearthed artifacts (Lu & Zheng, 2003). Though involving so many different individual sites, the houses and cemeteries were grouped together under the label of “Subeixi site” as per not only similarities found between different items but also as there were no other large sites of such items found in the nearby vicinity (Gong et al., 2011). Excavations performed at the site began in May 1980 (focusing on the house remains and cemeteries No. 1 & 2) and continued with the discovery of cemetery No. 3 in 1992 during major highway construction, most of which were headed by Professor Enguo Lu of the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology, in cooperation with other institutions.

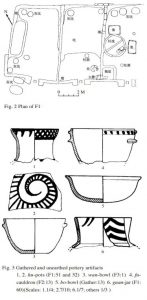

The three house remains covered an area of 400 m² and included items like scattered stone artifacts, woolen textile fragments, pottery shards, and adobe wall foundations (Lu & Zheng, 2003). The first house (F1) is described as rectangular in shape (13.6 m x 8.1 m), consisting of three separate rooms with the west most room containing an oblong trough, leading it to be interpreted as a room for food storage (with bits of straw and shells of broomcorn millet being found). The middle room contains a hearth-like structure, and the east room includes many differently shaped tanks and pits, causing researchers to believe it served as a pottery workshop. Much of items unearthed were millstones (grindstones), stone pestles, and potshards, with the potshards showing a variety of pottery types including fu-cauldrons, guan-jars, bo-bowls, wan-bowls, hu-pots, and lamps (Lu & Zheng, 2003). The other 2 housing remains are described as “badly preserved,” with very few artifacts being recovered and those that were being of very poor quality (Gong et al., 2011).

Layout of house F1, alongside images of unearthed artifacts showing the house’s use for crafting pottery.

Perhaps the more sensationalized parts of the Subeixi site are the cemetery artifacts that have been recovered, specifically those of human remains. Spread across three different labeled cemeteries (No. 1, 2, & 3), a total of 19 sets of mummified remains have been catalogued and recovered (13 identified as Caucasian, 3 as Mongolian/Mongoloid, and 3 as being of mixed race/ethnicity), with associated artifacts/grave goods appearing like those found in the house remains (Shevchenko et al., 2013). Cemetery No. 1, located 600 m north of the site, covers over 3000 m² and is split into two sections, with the east section containing 20 burials (8 of which were excavated in 1980, labeled M1-M8) and the west section containing 32 burials (5 excavated in 1980, labeled M9-M13) (Lu & Zheng, 2003). Of the western section excavations, consisting of 4 earth-pit and 1 cave-cum-shaft burials, held unearthed items of pottery, stone, iron, bronze, leather, and other woolen artifacts, with the human remains of one burial (M11) including a woman, man, and infant (Image below). Cemetery No. 3, located on a terrace 80 m west of the site (Area of 80 m x 20 m), was excavated in 1992, unearthing 30 burials and similar funerary objects like ceramic vessels (some containing food remains), wooden wares, ironware, stone tools, bone artifacts, and woolen/leather articles (Gong et al., 2011).

Complete set of mummified female remains found in labeled grave M11 at Cemetery No. 1 site.

Several recent examinations of this site have turned to food remains found within the cemetery grave goods, looking to reveal potential ancient food preparation techniques in the hopes of revealing similarities in these to other groups moving near/through this area at the time (Gong et al, 2011; Shevchenko et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2012). Utilizing methods involving proteomic examinations of food residue/remains such as sourdough bread (Svechenko et al., 2013) and milk components (Hong et al., 2012) as well as performing simulated cooking methods of cakes, millet, and noodles (Gong et al., 2011) found mostly within grave goods, the researchers present similar hypotheses that these preparatory procedures further indicate the Subeixi site as an integral part of eastern and western societal/group communication. With the Turpan basin constructed with the role of route for cultural communication, as well as with work done at other nearby sites like the Astana cemeteries and its evidence of Cannabis fiber being utilized in ancient burial practices (Chen et al., 2014), it may be possible to see that the East/West divide of Eurasia might have been closer than previously thought.

References

Chen, Tao, Shuwen Yao, Mark Merlin, Huijuan Mai, Zhenwei Qiu, Yaowu Hu, Bo Wang, Changsui Wang, and Hongen Jiang. 2014. “Identification of Cannabis Fiber from the Astana Cemeteries, Xinjiang, China, with Reference to Its Unique Decorative Utilization.” Economic Botany 68 (1): 59-66. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden Press.

Gong, Yiwen, Yimin Yang, David K. Ferguson, Dawei Tao, Wenying Li, Changsui Wang, Enguo Lu, and Hongen Jiang. 2011. “Investigation of ancient noodles, cakes, and millet at the Subeixi Site, Xinjiang, China.” Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 470-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.10.006.

Hirst, K. Kris. 2016. “The Gushi Kingdom – Archaeology of the Subeixi Culture in Turpan: The First Permanent Residents of the Turpan Basin in China.” ThoughtCo., October 16. Accessed May 9, 2017. https://www.thoughtco.com/gushi-kingdom-subeixi-culture-in-turpan-169398.

Hong, Chuan, Hongen Jiang, Enguo Lu, Yunfei Wu, Lihai Guo, Yongming Xie, Changsui Wang, and Yimin Yang. 2012. “Identification of Milk Component in Ancient Food Residue by Proteomics.” PLoS ONE 7(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037053.

Lu, Enguo, and Boqiu Zheng. 2003. “The Subeixi Site and Cemeteries in Shanshan County, Xinjiang.” Translated by Yi Nan. Chinese Archaeology 3: 135-142.

Shevchenko, Anna, Yimin Yang, Andrea Knaust, Henrik Thomas, Hongen Jiang, Enguo Lu, Changsui Wang, and Andrej Shevchenko. 2013. “Proteomics identifies the composition and manufacturing recipe of the 2500-year old sourdough bread from Subeixi cemetery in China.” Journal of Proteomics 105: 363-371. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.016.

Ulug Depe

May 9, 2017

Ulug depe, in what is now the nation of Turkmenistan, is an important Central Asian archaeological site. It is known for its pottery assemblages and citadel structural remains from multiple cultural layers, from the Late Namazga IV and V (Bronze Age) to the Yaz II and III (Iron Age). The remains of the site lie in the steppe of the eastern Kopet Dagh piedmont zone where alluvial fanning spread throughout the land starting from the Kelet River (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). The nearest major city is Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan, which is 175 km west of the site. The nearest small town is Dushak, about 5 km north. (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). Ulug depe’s coordinates according to Google Earth are 37 ° 09’17.38”N, 60 ° 01’46.42”E, and its elevation is 931 feet. The main citadel’s area is 1.7 square km. Although Ulug depe is the most common spelling, occasionally the archaeological site is referred to as Ulug tepe.

Archaeologists V. I. Sarianidi, K. A. Kachuris, and I. S. Masimov conducted multiple excavations at Ulug depe starting in the late 1960s and early 1970s (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). From 2001-2010, Lecomte, Bendezu-Sarmiento, and Mamedov took part in the Turkmen-French Archaeological Expedition (also known as the French-Turkmen Archaeological Mission) and excavated multiple trenches by Ulug depe’s main citadel. (Bendezu-Sarmiento & Lhuillier, 2011).

Various Yaz II potsherds from Ulug depe.

Ulug depe contains many cultural layers that denote its ages of occupation; in fact, it contains the longest stratigraphic sequence in Central Asia (Boucharlat et al., 2002). The main mud-brick citadel has been dated to the Iron Age/Yaz II period according to ten charcoal samples upon which radiocarbon dating was performed. This dating process determined the structure was built between 979–833 BCE to 799–759 BCE at 99% probability (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). Going deeper into the soil (and therefore further into the past), older ceramics were dated to the Bronze Age/Late Namazga IV and V periods. Potsherd slip testing specifically provided the dates of 2646 ± 100 BCE – 2690 ± 100 BCE (Masson, 1988). Clearly, Ulug depe was inhabited during drastically different time periods, and therefore it can be argued that different “cultures” lived at the site. However, it is most likely that the people who occupied the site during the different eras were actually similar people. Nomadism, trade, and environmental changes could have caused them to leave, then come back again generations later.

Many materials, especially pottery, have been found at the site of Ulug depe. Approximately 40 different pottery shapes have been discovered dating to the Iron Age/Yaz II period. In particular, pieces of large jars with convex walls and sealings typical of the Iranian Iron Age/Yaz II period were found in ground floor rooms of the citadel, indicating the citadel’s possible function for food storage (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). The jar sherds appear to be mainly coil-built and wheel-fashioned (despite a few handmade coarse wares for storage. Potsherds for the Yaz II period number in the hundreds, and more than half indicate closed, rather than open, profiles (Bendezu-Sarmiento & Lhuillier, 2011). Fine horizontal lines on much of the Yaz II period pottery walls indicate the wheel-throwing technique of pottery (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). Three paste types were found: fine and light, coarser paste with mineral temper, and very coarse. About a quarter of the pottery from Yaz II was decorated with painted motifs (Bendezu-Sarmiento & Lhuillier, 2011). What is unique to Ulug depe is the red slip covering some sherds.

Skeletonized remains of about 15 people were discovered, associated with potsherds and animal bones from the Iron Age. One of these graves included a two to four year old child from the Middle-Late Iron Age, with his arms positioned bent against the thorax and his body bent so that his feet almost touch his skull. These remains possibly indicate sacrifice and decarnization based on Zoroastrian religion and culture (Bendezu-Sarmiento & Lhuillier, 2011).

Pottery from Ulug Depe with characteristic red slip.

Ulug depe was probably the village center based on its large size and centrality of the citadel, which was built on the highest elevation of land in the immediate vicinity. The high concentration of pottery and evidence of a main road also point to its importance as a settlement center (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). Other smaller buildings that indicate the existence of a city were also excavated, such as a treasury and palatial complex associated with a fortification wall (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). In some of the remains of multiple-room houses at the site, two-story kilns were uncovered point to pottery firing in the Early Bronze Age (Kohl, 2015).

Many of the ceramics unearthed at Ulug depe represent the Yaz II culture, which is characterized by beak- and hooked-rim jars. Yaz II has been identified in other sites such as Bektepa, Kuchuk II, and Kyzylcha 6 (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). Chronologically, the Yaz II cultural period in Ulug depe dated to more recent times than these other sites, possibly because aspects of Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) culture took a longer time to reach the Kopet Dagh foothills. Related to this, the use of red slip indicates cultural contact with people of the Iranian plateau because similar slip has been found at sites such as Sialk A in modern-day Iran (Bendezu-Sarmiento et al., 2013). The archaeological evidence of wheel-made pottery beginning in the Yaz II period marks the transition between Bronze Age and Iron Age cultures. In the Bronze Age, pottery was mainly handmade coarse ware (Bendezu-Sarmiento & Lhuillier, 2011). The painting of pottery occurred in all layers including as far back as Namazga IV, but became the predominant style by Yaz II across Central Asia, and specifically at Ulug depe (Kohl, 2015). This evidence of cultures comes together to the conclusion that the Yaz II type artifacts did not arise autochthonously, but rather as a result of cultural contact between those at Ulug depe in the foothills of the Kopet Dagh and other cultures in the BMAC (Kohl, 2015).

Works Cited

Bendezu-Sarmiento, J., Dupont-Delaleuf, A., Lecomte, O., Lhuillier, J. “The Middle Iron Age in Ulug-depe: A preliminary typo-chronological and technological study of the Yaz II ceramic complex.” Marcin Wagner. Pottery and chronology of the Early Iron Age in Central Asia, The Kazimierz Michalowski Foundation. 2013.

Bendezu-Sarmiento, J. and Lhuillier, J. “Iron Age in Turkmenistan: Ulug depe in the Kopet-Dagh piedmont.” M. Mamedow. Historical and Cultural sites of Turkmenistan. Discoveries, Researches and restoration for 20 years of independence, Turkmen state publishing service, 2011.

Boucharlat R., Francfort H.P., Lecomte O., Mamedow M. “Recherches archéologiques récentes à Ulug Dépé (Turkménistan).” Paléorient, Vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 132-131. 2002.

Kohl, P. L. The Bronze Age Civilization of Central Asia: Recent Soviet Discoveries. Routledge, 2015.

Masson, V. M. Altyn-Depe. UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1988.

Sel-Ungur

May 8, 2017

Also Known as: Sel’Ungur, Сельунгур, Сель-Унгур, Селюнгур

Coordinates: 39.95°N, 71.32°E

Originally discovered in 1955 by A.P. Okladnikov, the Sel-Ungur cave-site was officially excavated in 1980 by Islamov’s team from the Soviet Institute of Archaeology (1988). Sel-Ungur is a Lower Paleolithic site located in the Alai mountain region of Kyrgyzstan and is one of the most significant finds of Paleolithic Central Asia. Most notably, it houses human remains whose origins have been recently disputed in anthropological literature. These remains may be critical in tracing the early hominids’ pattern of migration across inner Asia. Earlier finds, such as Teshik-Tash and Obi-Rakhmat, have clearly established a Neanderthal presence in the region and even suggested that these Central Asian Neanderthals were in contact with other species of humans during that time. Further research into the Sel-Ungur site may provide us with critical insight of what types of humans were living in Central Asia and when.

Map of Lower Paleolithic sites found in Central Asia. Taken from Davis & Ranov (1999).

Cave Site

The Sel-Ungur cave is located in the Ferghana basin of the Alai mountain system at an elevation of about 1,900 meters. The entrance to the cave itself is about 50 meters above the lower portion of the Katrantau Ridge. The site is 120 m long, and its width and height at the mouth are 34m and 25m respectively. Archaeologists have identified 5 main cultural layers (0.2-0.4m thick) separated by thin strata (0.3-1.0 m thick) and lying at a depth of 2.5 to 6.5 m (Markova, 1992). A uranium-thorium date of 126,000 B.P. ± 5,000 years was obtained on a travertine sample taken from the stratum overlying the upper cultural layer (Davis & Ranov, 1999).

In an extensive paleoecological analysis of the site, Velichko et al. (1991) were able to establish that the sediment strata enclosing the cultural layers were generally homogeneous, showing no significant changes of ecological conditions during the period of the archeological layers’ formation. Put more simply, pollen and sediment sample analysis suggest that in contrast to the drastic environmental changes characteristic of Central Asia during the Lower Paleolithic, Sel-Ungur’s climate has remained relatively stable over time. As previously suggested by Glantz (2010), it is probable that the cave’s location at the base of a mountain may have shielded the site from any severe climatic fluctuations. In this way, Sel-Ungur’s relatively stable climate may have attracted long-term human settlement.

Satellite image of Sel-Ungur cave opening taken through Google Earth

Tool Industry

The Sel-Ungur site contains the oldest and most expansive tool industry found in the Ferghana region of Kyrgyzstan. 1,500 stone tools were found on site, with most items made of jasper and slate pebbles, and a few others from volcanic rock (Islamov, Zubov, & Kharitonov, 1988). The most common type of tool found were short massive flakes with wide smooth platforms. Other prevalent artifact types included choppers, side scrapers, notches, retouched flakes, and fragments. Vishnyatsky (1999) was also able to identify at least one cleaver from the items found at the site. Importantly, however, almost no blades nor prepared cores were found at Sel-Ungur. Instead, the collection is mostly derived from pebbles that have been worked by discoidal and opposed platform-core techniques.

According to Glantz (2010), the Lower Paleolithic of Central Asia is comprised of four technological industries, each of which is identified by key tool types such as Acheulian-like bifaces, pebbles, cores and flakes, and “small” artifacts. The original excavators of Sel-Ungur considered the tool industry to be Acheulean because they believed that they had found a bi-facial hand axe within the artifacts. However, Vishnyatsky (1999) considers this particular hand axe to be morphologically vague and argued that the artifact be considered a stone core instead. Consequently, in the absence of true hand axes, as well as the tools’ morphological similarities to other pebble assemblies in the region, there is reasonable argument to attribute Sel-Ungur to the group of the Lower Paleolithic pebble industries of Central Asia. This culture is not often associated with Neanderthal tool industries, and suggests that another species of human may have been inhabiting the site.

Bifacially retouched artifact from Sel-Ungur Cave, Kyrgyzstan. Taken from Vishnyatsky (1999).

Animal Remains

In addition to the expansive stone artifacts found at Sel-Ungur, the site also contained 4,000 mammal bone fragments, most of which are badly preserved. The two upper layers of the site are dominated by wild sheep (Ovis cf. ammon), wild goat (Capra sibirica), deer (Cervus cf. elaphus bactrianus), and cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) remains. The third and fourth cultural layers yielded aurochs (Bos primigenius), rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus cd. Kirchbergensis), sheep, and goat. Other layers bore wolf (Canis cf. lupus), fox (Vulpes vulpes), cave hyena (Crocuta spelaea), cave lion (Panthera cf. spelaea), Pleistocene ass (Equus hydruntinus) and horse (equus sp.) The variety of species found in the Sel-Ungur animal remains were critical in categorizing the cave as a Lower Paleolithic site. Furthermore, the Sel-Ungur’s rodents were also useful for providing insight into the environmental conditions surrounding the prehistoric site. The rodents are represented by 10 species, most important of which are Neodon, Microtus juldaschi, Ellobius tancrei, Cricetulus migratorius, alticola argentatus, meriones libycus, and Ochotona rufescens. According to Markova (1992), such a composition of rodents (which does not undergo any significant change from layer to layer) is indicative of the existence of mountain steppes with patches of woods and shrubbery in the cave’s surroundings. These environmental conditions are usually attributed to the Middle Pleistocene age in Central Asia and provides strong evidence to that the site can be dated to this time period.

Wild sheep (Ovis cf. ammon) bones found in Layer 1 of Sel-Ungur Cave. Taken from Glantz et al. (2004)

Human Remains

Besides the animal bones, the Sel-Ungur cave deposits included some human and some putatively human remains. In the first excavation, six teeth (three upper incisors and three lower premolars) belonging to two or three individuals, and a humerus fragment were identified (Islamov et al., 1988). The original paleoanthropologists attributed these hominid remains to be from a local specialized variant of Homo Erectus. By comparing the size and shape of the bones to other human remains, Zubov and Islamov (1988) considered the Sel-Ungur individuals to be a species of humans that were somewhere between Homo Erectus and Homo sapiens neanderthalensis . However, a more recent analysis of the remains by Glantz et la. (2004) determined that the teeth are in reality a mixture of cave bear and possibly ungulate teeth, while the long bone is probably a juvenile hominin humerus, whose species is indeterminate. Although the origins of these human remains are still debated, Sel-Ungur remains a major Central Asian site because it provides us with the first Central Asian hominid fossil find since Teshik Tash. In response to the recent findings of diverse human species (Donisovans, Neanderthals, and Cro-magnons) in Central Asia, new research is currently underway to excavate the potential of Sel-Ungur’s human remains. Most notably, researchers are now determined to uncover the DNA origins of Sel-Ungur juvenile humerus to determine which species of human were occupying the site during the Lower Paleolithic period (Lykosov, 2016). Their identification will provide invaluable insight into the diverse populations of humans living and migrating in the previously understudied area of Central Asia.

References

Davis, R.S., & Ranov, V.A. (1999). Recent work on the Paleolithic of Central Asia. Evolutionary Anthropology, 8(5), p. 186-193.

Glantz, M. M. (2010). The History of Hominin Occupation of Central Asia in Review. Asian Paleoanthropology Vertebrate Paleobiology and Paleoanthropology, p. 101-112.

Glantz, M. M., Viola, B., & Chikisheva, T. (2004). New hominid remains from Obi-Rakhmat Grotto. In A.P. Derevianlko (Ed.), Grot Obi-Rakhmat (pp. 77-93). Novosibirsk: Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, Siberian Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences.

Islamov, U. I., Zubov, A. A., & Kharitonov, V. M. (1988). Paleoliticheskaya stoyanka SelUngur v Ferganskoi doline (The Paleolithic site of Sel-Ungur in the Fergana valley). Voprosy antropologii, 80, p. 38-49.

Lykosov, M. (2016, December 01). Archaeologists Resume Digging in Sel-Ungur Cave. Retrieved May 7, 2017, from https://english.nsu.ru/news-events/news/research/archaeologists-resume-digging-in-sel-ungur-cave/?sphrase_id=6710

Markova, A. (1992). Fossil rodents (Rodentia, Mammalia) from the Sel’- Ungur Acheulian cave site (Kirghizstan). Acta zool. cracov., 35(2), p. 217-239.

Velichko, A.A., Arslanov, K. A., Gerasimova, S.A., Gerasimova, A., Islamov, U.I., Kremenetski, K.V., Markova, A.K., Udartsev, V.P., & Chikolini, I. (1991). Paleoecology of the Acheulian cave site Sel-Ungur (Soviet Central Asia). Anthropologie, 24(1), p. 9-15.

Vishnyatsky, L.B. (1999). The Paleolithic of Central Asia. Journal of World Prehistory, 13(1), p.69-122.

Tamsagbulag

May 7, 2017

Alternate spellings: “Tamsag Bulag,” “Tamsagbulak,” “Tamsag,” “Tamsak Bulak,” Mongolian: “Тамсагбулагийг”

Tamsagbulag was a major site during the relatively understudied Mongolian Neolithic. While originally presumed to have been active during the 3rd millennium BCE, recent radiocarbon dating techniques place the site between 4753 and 4155 BCE (Okladnikov and Derevianko, 1970), (Séfériadès, 2004). This site, or constellation of sites, rather, served as the key location of a sophisticated but short-lived Tamsagbulag culture. This culture was characterized, among other things, by both sedentary hunter-fisher-gatherers and agriculturists who occupied southeastern Mongolia and northern China during the late Neolithic.

(Location of Tamsagbulag within Mongolia) (Séfériadès, 2004)

Tamsagbulag lies in the Dornod region – the easternmost province of Mongolia – just a few kilometers away from the Chinese border (Manchuria) (see figure 1). The sites can be accessed after a five-hour drive southeast from the town of Choibalsan, the province’s capital. In Mongolian, “Bulag” means spring, and it’s likely that a fertile spring once existed here though the area today more closely resembles a dry desert steppe (Okladnikov and Derevianko, 1970). Most of the sites in Tamsagbulag are situated on a high plateau terrace (at an elevation of 700 m) with a flood plain at its foot. About 1 km away from the area exists the remains of a large, shallow lake that is almost completely dry today. Natives of the region, in conjunction with some fossil finds, suggest that the area was once rich in gazelles, boar, and saiga antelopes before the Soviet Army drove them out (Séfériadès, 2004).

The site itself is constituted by at least three major clusters (villages?) of semi-subterranean, quadrangular, wattle-and-daub houses. As a whole, this constellation of houses occupies around 12-13 km of area, with each house individually spanning 30-40m2 (7.60 m long, 5.60 m wide and 0.60 m deep) (Séfériadès, 2004). The position of the houses atop the plateau allowed for its inhabitants to observe the surrounding landscape and its fauna. The houses all lack any ostensible windows or doors, suggesting that the inhabitants entered and exited through the pyramidal roofs (Dani, 1993, 172).

Several artifacts have been discovered in each of the three recorded ‘villages’, all of which suggest a very distinct, relatively advanced Tamsagbulag culture. Tamsagbulag 1, which was first investigated in 1970 by a Russian research team led by A. P. Okladnikov and A. P. Derevianko, revealed several stone implements made from flakes and cores of a variety of shapes. One such shape of core scraper was so anomalous that it is now referred to as the “Tamsagbulag type” (Dani, 1993, 172). The Tamsagbulag type of stone tools is characterized by “a bevelled striking surface fashioned by making transverse chips. The flakes were removed from only one side and the shoulder was cut into a point or wedge shape” (Dani, 1993, 172) (See figure 2). At the time of Tamsagbulag 1’s discovery, tools of this nature were entirely unique to the Tamsagbulag culture alone. In addition to these distinct scrapers, remnants of arrowheads, hammers, adzes, and primitive hoes were also found in great quantity. The presence of these artifacts, in addition to fossil discoveries of ostensibly domesticated livestock, suggest that the Tamsagbulag people enjoyed a relatively rich and sophisticated culture of hunting, gathering, fishing, and even agriculture (Dani, 1993, 172).

(Illustration of Tamsagbulag stone tools) (Dani, 1993)

Further evidence of the sophistication of the Tamsagbulag culture was discovered during a second excavation of the site in by a French research team led by Séfériadès (1997). This session revealed the sites of Tamsagbulag 2 and 3, which were discovered on the opposite bank of the ancient lake (Séfériadès, 2004). In addition to the discovery of these sites, several new artifacts were also unearthed, including chipped stones, ceramics, and grave goods. The chipped stone remnants discovered at both of these sites suggest a diverse and thriving stone industry within Tamsagbulag culture. Many utilitarian stone remnants were found, including bladelets and fragments of both adzes and hoes, further suggesting that the inhabitants of Tamsagbulag engaged in some form of early agricultural behavior. This behavior has been referred to as the earliest known indicator of farming in Mongolia, and helps provide a narrative about Central Asian cultures during the Neolithic that deviates from the traditional nomadic archetype (Eisma, 2012).

In addition to stone tools, the research team discovered semi-precious stones of a variety of colors, such as jasper, quartz and chalcedony (Séfériadès, 2004). They were also able to recover two pieces of obsidian, which are not native to the area, and may suggest the presence of medium and long-distance exchange network patterns within the Tamsagbulag culture (Séfériadès, 2004). Following these discoveries, Séfériadès began to refer to the inhabitants of Tamsagbulag as “les preimiers paysans de Mongolie,” or, “the first peasants of Mongolia” (Séfériadès, 7, 1999).

Excavation of all three Tamsagbulag sites have also yielded pottery fragments from the Neolithic and possibly Early Bronze Age (Séfériadès, 2004). These pieces of pottery are also seen as a distinct aspect of the Tamsagbulag culture, as “nothing like it has been found among remains from the same period in other parts of Central, North and East Asia” (Dani, 173, 1993). The fragments are distinguished by grey, thick-walled, friable, pieces of clay with high sand content and geometrically incised or impressed surfaces (Dani, 1993), (Séfériadès, 2004). The distinct nature of these ceramic fragments are seen by Dani (1993) as “unquestionable evidence” of a local thriving ceramic industry (172).

A third indicator of a relatively sophisticated, distinct Tamsagbulag culture is found in their burial customs. Tamsagbulag burials were first reported by Okladnikov and Derevianko (1970), when the researchers found human skeletal remains beneath the floor of Tamsagbulag 1. Remarkably, the skeletons were discovered in a sitting position, which is almost entirely anomalous in Europe and Asia and more akin to mummies of ancient Peru (Séfériadès, 2004) (see figure 3). A series of grave goods accompanied these skeletons, including bone knives and necklaces fashioned from Maral incisors and mother of pearl beads (Séfériadès, 2004) (see figure 4).

(Recreation of Tamsagbulag burials) (Séfériadès, 2004)

(Illustration of necklace found in Tamsagbulag burial site) (Séfériadès, 2004)

(Illustration of necklace found in Tamsagbulag burial site) (Séfériadès, 2004)

Fortunately, a scholar by the name of Alex Humbolt has already mapped out key sites of the Tamsagbulag expeditions on Google Earth. In my opinion, the most impressive set of coordinates, (47°15’46.65″N, 117°17’23.50″E) depicts what appears to be an ancient Neolithic, Tamsagbulag village with many houses. The site becomes visible from an eye altitude of 13,869 feet and spans an area of roughly 7km. However, from the Google Earth view, it’s difficult to discern which notches in the earth are ancient houses and which are the result of archaeological excavations. Another set of coordinates: (47°16’20.25″N, 117°16’9.38″E) very clearly show the remnants of a few long semi-subterranean houses characteristic of Tamsagbulag culture. These houses individually are consistently 42 m long and 7.5 m in width and are still remarkably visible today.

References:

Séfériadès, M. L. 2004. An aspect of Neolithisation in Mongolia: the Mesolithic-Neolithic site of Tamsagbulag (Dornod district). Universités Rennes 1, Laboratoire d’Anthropologie. Retrieved from: <http://revije.ff.uni-lj.si/DocumentaPraehistorica/article/view/31.10>

Séfériadès, M. L. 1999. A Tamsagbulag, les premiers paysans de Mongolie. Archeologia 0570-6270. Retrieved from: <http://cat.inist.fr/?aModele=afficheN&cpsidt=2022715>

Dani, A. H. 1993. History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B.C. United Nations Educational.

Eisma, D. 2012. Agriculture on the Mongolian Steppe. The Silk Road. Retrieved from: <http://www.silk-road.com/newsletter/vol10/SilkRoad_10_2012_eisma.pdf>

Humbolt, A. 2006. Mongolia – Tamsagbulag neolithic site (5.000 BC) Google Forums. Retrieved from: <https://productforums.google.com/forum/#!topic/gec-history-illustrated/LfqBNkf0n18>

Okladnikov, A. P., and A. P. Derevianko (1970). Tamsag-Bulak. Neoliticeskaja kul’tura Vostocnoj Mongolii. Materiali po istorii I filologii Tsentral’noy Azii 5: 3–20.

Sarazm (Саразм)

May 7, 2017

Sarazm ( Саразм) is an Aneolithic site located in Western Tadjikistan in the Sughd region about 5.0 km from the Uzbekistan border. Situated on the Samarkand plain on the left bank of the Zarafshan river, Sarazm provides evidence for a sophisticated sedentary settlement with agricultural and metallurgical advancements in the Steppic landscape (Isakov 1981). Sarazm is located at N39 30 28 E67 27 37 (UNESCO World Heritage Convention).

The site is easily identified using Google Earth, coming into view at approximately 6,500 ft. The entire site’s total area is approximately 130,100 m2 and its perimeter is approximately 1,682 m. Its elevation is around 3020 ft (Google Earth).

Excavations sponsored by the USSR began in 1976 under Abdullah Isakov. During this initial period there were two small villages, Avazali and Sokhibnazar, on either end of the site and Penjikent was the nearest city at 15 km east (Spengler and Willcox, 2013, 213). Today the area is more populated, featuring developed areas on the outskirts of the site (Google Earth). Later excavations were done collaboratively between Isakov, his team and French and American archaeologists after the dissolution of the USSR. The site has been excavated and researched continuously since the initial dig.

Circular building (Besenval and Isakov 1989, 9)

According to Isakov et. al (1987) Sarazm dates back as early as the fourth millennium BCE placing it around 6000 years old via radiocarbon dating of materials such as clay and bones (90). Isakov et al.(1987) divides the chronological frame of Sarazm into three distinct phases; Sarazm I is dated to the early fourth millennium, Sarazm II to the late fourth and early third millennia, and Sarazm III to the later half of the third millennium (90). According to a later archaeologist Razzokov (2008) there are four distinct occupation phases; Sarazm I dates from 3500-2900 BCE, Sarazm II from 2900-2600 BCE, Sarazm III from 2600-2300 BCE, and Sarazm IV from 2300-2000 BCE (Spengler and Willcox 2013, 213). Razzokov’s phases are more supported and concrete, as dating techniques have improved.

Isakov’s initial excavations unearthed multiroom buildings, burials, and other artifacts including pottery, stone objects, and metal pieces. During the second excavation, evidence of occupation during all three of Isakov’s phases was discovered.The findings from the Sarazm I phase were limited due to disturbances from later building by the former occupants of the site. A courtyard and three rooms were found; two of the rooms were connected by a doorway. The Sarazm II phase findings included five living complexes, each having an exit to a courtyard containing a hearth and bread oven (Isakov 1981, 274). Within the Sarazm III phase, more rooms were found along with five burials of two children and three adults. These graves had no grave goods, instead artifacts such as bones, ceramics, and ashes were found in courtyards (Isakov, 1981, 276). Circular hearths found within some of the rooms showed parallels in design to those in Turkmenian sites Geoksyur and Aina-depe.

Excavation II map (Isakov 1981, 275)

Isakov’s third excavation contained the remains of seven rooms constructed from brick unlike the former excavation which had clay as the predominant material. This complex is suggested to be a communal building with storage areas for grain, supported by its layout and the lack of material remains within the complex (Isakov 1981, 278). The ceramic fragments found are of particular interest to researchers because of their painted nature and similarity to those of the Namazga culture from southern Turkmenistan. The pottery was either polychrome, featuring dark-brown and dark-rose designs on red or light-yellow backgrounds, or monochrome with dark-brown designs on a lighter background. The triangles and sawed designs within rectangles on certain ceramics parallel designs from Geoksyur and Kara-depe (Isakov 1981, 278). Issakov and Lyonnet (1988) note that there is an absence of local ceramics and suggest that this is because those from Turkmenistan colonized Sarazm (42). Sarazm was an ideal location because of its proximity to lapis-lazuli and mineral rich mountains, its proximity to the Zerafshan River, and its formation and preservation of long term trade (Issakov and Lyonnet 1988).

Ceramic fragments studied by Issakov and Lyonnet (1988, 41)

Reconstructed ceramics (Isakov and Besenval 1989, 15).

According to Isakov (1981) stone objects such as plummets, cups, mortars, grinding stones, pestles, spindle whorls, beads, jambs, and whetstones showed similarities to those from Anau, Kara-depe and other non-Central Asian sites including those in Iran and Afghanistan (279). Bronze knives, daggers and an axe-adze were found indicating the presence of metallurgy.

Excavation III Map (Isakov 1981, 277).

During Isakov’s fourth excavation four terracotta venus statuettes were found (Isakov 1994, 4). One statuette with a bird-like head shows similarities to statuettes found at Göksür, but, overall, the statuettes resemble those found in Southern Turkmenistan. Bone awls, piercers, and needles were found, suggesting they were used in conjunction with bronze tools. Shells were also found suggesting that contact was established and maintained with distant places (Isakov 1994, 5). Four other burials with grave goods were found, contents included domestic and cosmetic objects including a bronze mirror, seashells, and gold and silver beads indicating the high statuses of those buried (Isakov 1994, 6). Isakov’s later excavations revealed religious buildings along with more communal buildings and residential buildings.

Evidence for metallurgy at Sarazm include vast amounts of bronze tools and ornaments along with stone metal-casting molds and crucibles. Tools included daggers, knives, a fishhook, spear tips, darts and needles while other objects included beads, a mirror, a stamp and pins. (Isakov 1994, 9). Isakov et al. (1987) studied the chemical composition of metals present in the objects found, showing that many are essentially pure copper combined with lead or iron in some cases (100). Cold-working produced the bronze mirror found; this process involves hammering the metal to the desired shape and then heating it to 500 Celsius. Other objects were produced in the more traditional manner of heating and then pouring into a mold. The latter method is similar to other metallurgical contemporaries in Mesopotamia, Iran, and the Indus Valley (Isakov et al. 1987, 101). Sarazm’s copper was likely smelted from malachite, cuprite, or azurite from the Zerafshan Valley. The settlement likely had its own stores of metal since many objects come from the same smelting batches (Iakov et al. 1987, 101).

Bronze daggers and bronze axe-adze (Isakov 1981, 284)

Evidence for the agricultural nature of Sarazm include archaeobotanical analysis of seeds at the site. (Spengler and Willcox 2013). Seed samples, taken from hearths, house floors and middens, were analyzed by flotation, allowing comparison between native flora of the area. Wheat and barley seeds were found along with other wild flora suggesting that the settlement did grow crops but also still depended on native flora to survive (Spengler and Willcox 2013). Lentils were also found, however, their wild or domestic origin is unclear. Sarazm’s granary along with bread hearths near residential areas suggest that they had a surplus of grain from farming (Benseval and Isakov 1989). Sarazm also depended on herding, as shown by the remains of sheep, goat and cattle, however hunting of gazelle, wild pig, fox and birds also supplemented their diet (Spengler and Willcox 2013, 214). It is theorized that since the area is unable to be irrigated traditionally that dry farming was implemented (Spengler and Willcox 2013).

Sarazm is an ancient permanent settlement known for the presence of agriculture and metallurgy. The site contains multi-room residential complexes, communal buildings complete with granaries, religious buildings, and areas where burials have occurred. Sarazm demonstrates a greater span of communication during the Aneolithic period as evidenced by the similarities its ceramics and metal objects show compared to Turkmenian, Iranian, and Mesopotamian sites. It is likely a member of the same culture that Namazga sites as evidenced by the analogous designs and paintings on ceramics.

Besenval, R. and Isakov, A. “Sarazm et les débuts du peuplement agricole dans la région de Samarkand.” Arts Asiatiques Vol. 44 (1989), pp. 5-20. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43484861

Isakov, A. “Excavations of the Bronze Age Settlement of Sarazm.” Soviet Anthropology and Archaeology, 1981, 19:3-4, 273-286, http://dx.doi.org/10.2753/AAE1061-1959190304273

Isakov, A. “Sarazm: An Agricultural Center of Ancient Sogdiana.” Bulletin of the Asia Institute. Vol 8, 1-12. 1994. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24048761

Isakov, A., Kohl, P. L., Lamberg-Karlovsky, C. C. and Maddin, R. (1987), Metallurgical Analysis From Sarazm, Tadjikistan SSR. Archaeometry, 29: 90–102. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1987.tb00400.x

Isakov, A., and Lyonnet, B.. “Céramiques De Sarazm (Tadjikistan, URSS): Problèmes D’échanges et de Peuplement à la Fin du Chalcolithique et au Début de l’âge du Bronze.” Paléorient, vol. 14, no. 1, 1988, pp. 31–47., www.jstor.org/stable/41492267.

Spengler, R. and Willcox, G. “Archaeobotanical results from Sarazm, Tajikistan, an Early Bronze Age Settlement on the edge: Agriculture and exchange.” Journal of Environmental Archaeology. 2013. Vol.18:3. 211-221.

UNESCO “Proto-Urban Site of Sarazm” http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1141

Maibulak (example)

April 16, 2017

Also: Maybulak / Майбұлақ (Kazakh) /Майбулак (Russian)

Location: 43° 9’5.01″N, 76°23’7.79″E (Mica Glantz, personal communication)

Elevation: 1044 m

Maybulak is an Upper Paleolithic site located on the outskirts of the town of Kargaly, about 40 km west-southwest of Almaty in Kazakhstan. At an elevation of around 1000 m, it is in the northern foothills of the Zaili Alatau range of the Tien Shan mountains (Taimagambetov, 2010); just to the south on the opposite side of the mountains is Lake Issyk Kul.

The site was excavated first in 2004 by archaeologists from Al Farabi University and the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology in Novosibirsk, Russia (Taimagambetov, 2010). Later excavations saw collaborators from Nazarbayev University in Astana, Kazakhstan and the Max Planck Institute in Germany. Professor Cofran (formerly of Nazarbayev University) participated in excavations in 2014 when it came to light that the team had spent a month digging through what turned out to be back-dirt used to refill the site from previous excavations. It wasn’t his fault! Excavations are set to continue under the direction of Dr. Radu Iovita at New York University (Radu Iovita, personal communication).

The site is important for two main reasons (Taimagambetov, 2010). First, it is the first stratified Paleolithic site in the Zhetysu oblast of Kazakhstan. Most archaeological discoveries from this period are from deflated geological surfaces (Chlachula, 2010), lacking stratigraphy. Second and related, because the site has several clearly delineated strata, the different layers can be dated. Fortunately, the presence of charcoal provides material for radiocarbon dating – the first radiocarbon dates for any Paleolithic site in Kazakhstan (Taimagambetov, 2010). The third or lowest stratum was dated to 35 ± 0.6 kya, the second to between 30-27.5 kya, and the first and highest stratum to 24.3 ± .2 kya. This time period also saw two large “pulses” loess accumulation (Fitzsimmons et al., 2016), which may have facilitated preservation of these archaeological materials.

Chronologically placed in the Upper Paleolithic period, the artifacts are said to be “transitional” between Mousterian or Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic tools (Taimagambetov, 2010), as is characteristic of many comparably-aged Central Asian sites (Vishnyatsky, 1999). Tools include choppers, side-scrapers, blades …. [say something more meaningful than this, such as what kinds of tools are found, what is most common, what is most interesting, raw materials, etc.].

Figure 2 from Taimagambetov, nd., showing selected artifacts from Horizon II at Maibulak. [In a real post, you’d want also to point out what’s significant in the image that you want the reader to know. In this case it might be significant that #s 3 and 6 are scrapers that have been retouched]

Using Google Earth, the site is clearly identifiable. The visible excavation is rectangular measuring 10.2 x 29.5 m, with an area of about 286 square meters. The site is only 18.4 m away from a road. The site is just downhill from a cemetery, 144.3 m due east at an elevation of 1070 m. The closest, stratified Paleolithic site to Maibulak is Valikhanova, in the Karatau range of the Tien Shan. Measuring the distance between the two sites on Google Earth, Valikhanova is nearly straight west (heading 89.52º) 557 km (both ground- and map-length

References

[Note there are few publications on this site, as it was only recently discovered. Nevertheless, by drawing on other, relevant articles in the discussion, we’ve easily achieved the minimum of 4 peer-reviewed journal articles and 1 non-English reference]

Chlachula J. 2010. Pleistocene climate change, natural environments and Paleolithic occupation in East Kazakhstan. Quaternary International 220: 64–87. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.09.011

Fitzsimmons K, Sprafke T, Zielhofer C, et al. Loess accumulation in the Tian Shan piedmont: Implications for palaeoenvironmental change in arid Central Asia. Quaternary International, in press. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2016.07.041

Fu Q, Li H, Moorjani P, et al. 2014. Genome sequence of a 45,000-year-old modern human from western Siberia. Nature 514: 445–449. doi:10.1038/nature13810

Glantz M. 2010. The history of hominin occupation of Central Asia in review. In Asian Paleoanthropology: From Africa to China and Beyond, eds Norton and Braun. Springer Science+Business Media BV, pp. 101–112.

Taimagambetov Zh. 2009. Maibulak – First stratified Paleolith site in Zhetysu. Scientific Fund March-June. [Note this isn’t an ideal reference for the assignment since it’s from the internet, so difficult to verify peer review or other credentials]

Taimagambetov, Zh. nd Новые сведения о палеолитической стоянке Майбулак (New information about the Maibulak paleolithic site). Institute for Archaeology. Translated from Russian. <http://archaeolog.kz/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=105:2013-09-25-09-36-00&catid=19:—–2&Itemid=25&lang=en>

Vishnyatsky 1999. The Paleolithic of Central Asia. Journal of World Prehistory 13: 69–122.