In 1991, Lipp's son's Boy Scout troop built a bridge over the Casperkill in the Lipps' backyard. They used logs and rope.

Ron Lipp is a dedicated member of The Casperkill Watershed Alliance and longtime resident of Hagan Town. We talked with him on June 18th about his experience living in the watershed and working with the CWA.

Liz Jones: How long have you lived in the watershed?

Ron Lipp: I’ve lived here for 22 years.

LJ: In the same house?

RL: In the same house. We moved here from Ann Arbor, Michigan. One of the things that attracted us to the house that we live in was its location on the water. It made it very attractive and it was in the school district that we wanted.

Nadine Souto: What role did you envision the stream playing in your life at that point?

RL: Well, when you see a house with water… to me it represents beauty, serenity, a peaceful setting to enjoy. We have a deck at the back of our house and that deck is a highlight because we can sit out there and enjoy the stream and all the wildlife that goes along with it.

LJ: Has your perception of the stream changed since you first moved here?

RL: I have observed significant erosion on the other side of the stream, on our neighbor’s property, since the storm drain empties into the creek right behind our house. There is significant flooding of the stream with every significant rainfall. I have taken pictures many times when it floods and people will come to our yard to see if we float away.

LJ: Was that always the case or did that start after a certain point?

RL: Our basement is probably 25 feet from the stream and that was a question I had when I bought the house. I asked the previous owner if she had had any problem with the flooding and she said that neither she nor the previous owner had ever had a problem. So, with that description, I felt reasonably assured.

NS: And has your basement ever flooded?

RL: Never. Although when we get significant rain, I wonder how much it would take.

NS: How would you describe your relationship to the Casperkill? How do you or your family interact with it?

RL: I feel that we are part of it because we live on it and our property line actually goes through the middle of it. We have a double lot, so I would say that we have a significant portion of the Kill that we consider ours. It is not only part of nature and our neighborhood, it is part of our homestead.

LJ: Did your kids play in the stream?

RL: We didn’t encourage it, because we weren’t sure how safe that would be. There were occasions when we would see foaming material, colorful water and we weren’t sure where the contaminants were coming from and how serious they were. So we encouraged our children not to play in the stream, though it was pretty hard to keep them totally out.

NS: Did you ever get any official notification or information about the health of the stream?

RL: Never. I first learned about the health of the stream when I attended a watershed presentation at Vassar College about four years ago, when they shared the results of their study. That was confirmation enough for me not to have people go in it and certainly not drink it or expose oneself to the hazards of the water.

LJ: Did you see those kinds of things pretty much throughout or did it get worse at any point?

RL: It doesn’t happen too frequently, but once a year, on average, I see something in there that doesn’t look natural.

LJ: How did you hear about the Casperkill Watershed Alliance?

RL: Through the newspaper, when they announced that there was going to be a meeting at the college. I attended probably one of the first presentations by the faculty. Since I lived on [the stream], I was interested in it, and so I became aware of [the Alliance] and was probably one of its first members.

LJ: Why is that group important to you? Why do you keep going?

RL: I think I have become, because of the Alliance, more of an advocate for watersheds and their importance for the water supply and the environment. Through the Alliance, I learned that we as homeowners could take steps of our own to improve the health of the watershed, namely by reducing or eliminating our use of pesticides. And I made a significant change in our lawn care as a result of the knowledge gained through the Alliance. Another thing that we are encouraged to do is to grow plants and leave grass long along the stream, which I have done personally and encouraged neighbors to do. For example, the neighbors behind us, where I observed significant erosion, I not only recruited them to participate in the Alliance but also encouraged them to leave the grass long and make plantings to prevent further erosion.

LJ: How long ago was it that you started doing those things?

RL: Well, since I’ve been with the Alliance, I have been advocating for the plantings. This year was the first year that I made a change in my lawn care, because, while I volunteered to be an advocate for the watershed, we created a one-page flyer that could be used in neighbor-to-neighbor campaigns and one of the first suggestions says ‘reduce or eliminate the use of pesticides.’ That’s when I realized that if I’m going to be an advocate, I have to practice what I preach. So as a result of that, I requested of my lawn care company that they use only organic or natural substances, which they have complied with.

NS: And have your observed any direct results of that, in terms of the health of the stream?

RL: Of course not, but I feel much better about it. And I have learned to accept dandelions as part of my environment. So, my new motto is ‘dandelions are beautiful.’

LJ: Do you have any other specific memories of the stream?

RL: As I mentioned, we really enjoy the wildlife associated with the stream. There is a large flock of mallards that live in and around the stream year-round. And I suspect by our feeding them, we’ve assured that they’ll stay close-by. And that is enjoyed by our children and neighborhood children who love to come by and feed the ducks. There are also some Pekins that are here, not because they are native but because families, around Easter time, buy ducklings for their kids. When they outgrow their little cages and wading pools, they get deposited in a body of water and become domesticated to our neighborhood.

NS: Going back to your involvement in the CWA, what is your vision for the future of the Alliance? What role do you think it can play in the community?

RL: Well, my approach would be to do it one neighbor at a time. I think through targeted mailings and continual recruitment of people who live on or near the Kill, we could continue to educate and inform and encourage people to promote its health.

NS: Are there any other values that you see in the Casperkill, either for yourself or the community at large?

RL: I’ve seen children fishing in the stream. I’ve seen people coming to observe the wildlife, the frogs, the turtles, the fish… But another benefit to working with the Alliance is collaborating with faculty and students at Vassar College who also have interest in the environment. It’s made the whole project more stimulating and challenging.

Photographs courtesy of Ron Lipp.

Posted in Casperkill | Tagged Casperkill Watershed Alliance, erosion, flooding, Hagan Town, homeowner, lawn care | No Comments »

When Nadine and I approached Chris Scott, his dog Pebbles was frolicking happily in the Casperkill. Chris, a resident of Meadowview Drive, told us that whenever he is home (he currently attends college in Virginia), he and Pebbles frequent Hagantown Park. Pebbles is particularly fond of swimming in the stream and eating the stream-side vegetation; “I think it cleans her teeth,” Chris explained.

When Nadine and I approached Chris Scott, his dog Pebbles was frolicking happily in the Casperkill. Chris, a resident of Meadowview Drive, told us that whenever he is home (he currently attends college in Virginia), he and Pebbles frequent Hagantown Park. Pebbles is particularly fond of swimming in the stream and eating the stream-side vegetation; “I think it cleans her teeth,” Chris explained.

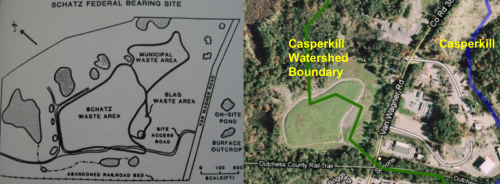

The abandoned Schatz Federal Bearing Company waste disposal site can be seen from the Rail Trail.

The abandoned Schatz Federal Bearing Company waste disposal site can be seen from the Rail Trail.