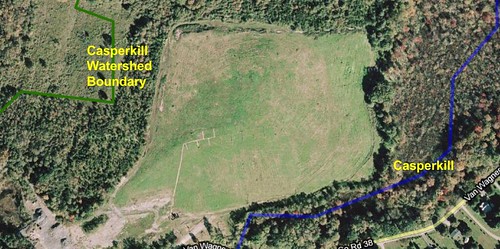

This manhole is only a few yards away from the Casperkill. It overflows sewage into the creek during heavy rain storms.

This manhole is only a few yards away from the Casperkill. It overflows sewage into the creek during heavy rain storms.

Residents on Old Mill Drive spoke with us about sewage in the creek, and about all of the deer (and Lyme disease) that the creek attracts.

On December 21, 2006, Michael Mayfield of the Poughkeepsie Journal spoke with residents along Old Mill Drive about sewage seeping through residents’ backyards before emptying into the Casperkill. The sewage had polluted the creek so much that it became difficult for wildlife to thrive. Olga Carmel told Mr. Mayfield “It’s not the same creek as when I moved here many years ago…there used to be fish, heron; I had pheasants in my backyard. Now there are only deer.”

Three and a half years later, the situation has not improved. Sonia, a homeowner along Old Mill Drive, talked with us about the manhole that repeatedly overflows into her backyard during periods of heavy rainfall. “The sewage just goes into our yard. Like last week, when it rained really hard, the ducks were swimming there! I mean, it was beautiful to see them because there was a momma duck with the little ducklings. It was cute to see that, but it was in sewage on the lawn, you know, not in the stream where they really should be.”

Although Sonia and her neighbors have been writing to the Town of Poughkeepsie for several years, they have not yet gotten a response. “We are not even expecting them to do it for free, it’s just that this is their thing and it is against the law to even touch it. We cannot bring a plumber. We can’t do anything.” Left with no other options, Sonia’s neighbor resorted to building a small white fence around the manhole to try to keep her grandchildren away from the sewage.

A few houses downstream, homeowner Richard Partridge said that, aside from some toilet paper in the stream after heavy rains, sewage in the stream does not affect him too much. Instead, he identified deer as the biggest problem confronting residents living along the creek. Deer are rampant in the lower part of the Spackenkill neighborhood due to all of the open space and shelter on the nearby Casperkill golf course. Mr. Partridge once counted twenty deer in his backyard, although there are usually around three or four at a time. He hopes that the Town might some day act to reduce the deer population to a sustainable level in order to cut down on the Lyme disease in the area. “I am delighted to have a buffer space behind me. We get all sorts of wild turkeys and other things in the backyard…I don’t mind having wildlife. It’s just that I wish the deer wouldn’t eat all of my stuff all the time, they’re just a little bit too prevalent.”

Information from:

Mayfield, Michael. “Forum to look at Saving Stream.” The Poughkeepsie Journal 21 December 2006.

Posted in Casperkill | No Comments »