How was the Casperkill formed?

June 18, 2010 by admin

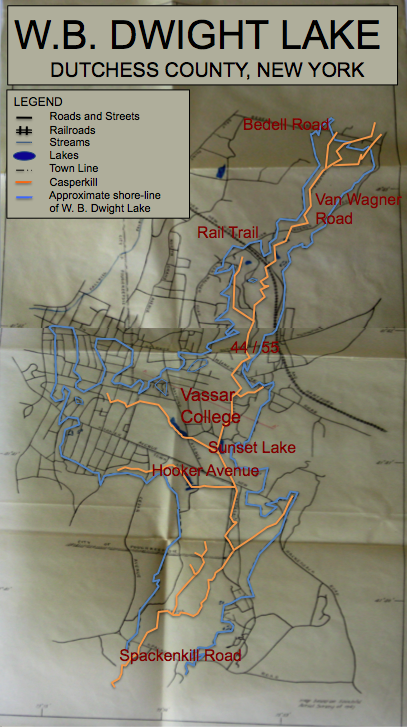

A map of Lake Dwight from Marlyn Magnus’ 1957 thesis.

In 1957, Vassar student Marlyn Mangus completed a senior thesis in Geology in which she identified and mapped the boundaries of a glacial lake that formed in front of the retreating Laurentide ice sheet. This lake, which she named Lake Dwight, is thought to underlie much of the town of Poughkeepsie, stretching from the Peach Hill Park area north of the Vassar Campus southward to Spackenkill Road.

Continental ice sheets covered much of North America and northern Europe during the Pleistocene (2.588 million to 12,000 years before present). As the earth warmed and these glaciers retreated, they eroded land away and in some cases left behind glacial lakes. When glaciers retreated, blocks of ice were sometimes isolated from the ice front and were left near the lower reaches of valleys. The ice blocks acted as dams, impounding water in the valleys until the ice klaved off and the lakes could drain out.

In her 1957 thesis, Marlyn Magnus proposed that this sort of thing occurred in what is now the valley of the Casperkill:

Ice blocks must have been isolated from the main ice front and left below what is now Spackenkill Road, forming a dam and backing up the water as far as Bedell Road. Thus a lake was formed which has been named the W. B. Dwight Lake. Streams running into the lake brought material, which was deposited on the floor of the lake. Eventually the ice blocks melted, leaving klaves (which can be seen south of the Spackenkill Road), and the water drained from the lake. A stream, the Casperkill, developed upon the old lake clays, and it is this stream which now drains the valley.”

About 50 years after Magnus first proposed and mapped Lake Dwight, students in a paleoclimatology class at Vassar College proved its existence. The students analyzed a 33 meter-long sediment core from the Vassar Farm (thought to be in the middle of the glacial lake) looking for pollen, evidence of trees, grain size (size can tell us where the water was coming from…whether the core was in the middle of the lake or at the edge of the lake), and other organic material. Emily Vail and I sat down to discuss what the class found: “All we found the whole way down, aside from some sand and iron at the surface, was (drum roll please)… grey, Gley, clay”

Not very exciting…but it did prove that Lake Dwight existed, and that it was pretty large and long-lived. All that clay was deposited while the lake was around. Vail told me that the class was still a great experience, and that it gave her a very different perspective on the landscape:

Thinking about time frames like the Pleistocene was just really far out for me. That’s a really long time ago. And it was amazing to go back and look at this thesis, and to think about what this place looked like during the ice age. To think about how with the Casperkill…we have a big valley out there. Why does it look that way? Well, partially because of Lake Dwight, and partially because the Casperkill has come in after the Pleistocene.”

We are often reminded of how the land affects us: how it affects vegetation cover, where we develop, the kinds of things we might do in a particular area. But by imagining Lake Dwight we are encouraged to think about something that we almost never consider. That is, how land is actually formed, how it came to look the way it does.

Information and map from: W. B. Dwight Lake, Dutchess County, New York, Marlyn Mangus, Dept. of Geology, Vassar College, January 1957

Personal interview with Emily Vail, June 11, 2010.