[This is the final section of the blog post “how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands”]

The two ideal types that I’ve been developing over these two blog posts — the Thornhill sound and the OCA band — converged with the biggest effect in Martha and the Muffins. The group began in May 1977 when Oh Those Pants! member David Millar suggested to fellow OCA student Mark Gane that they write some songs. Both were students of Udo Kasemets, so the offer implied a more serious approach than was typical of QSW bands at the time.

[David Millar] was another Sound Lab monitor, which meant we had access to it; we could use it in off hours. He had been in a bunch of bands with Martha, and one day he said, “Hey, do you want to start a band?” Because I used my guitar a lot for ambient stuff, too, like sort of drony things, almost like a prepared piano, putting things in the strings, and rattling it around, all that stuff… As soon as somebody says that, all these things flash through your head. Like, wow that would be kind of scary, because you’d have to get up in front of an audience, but you’re also flashing back to seeing the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. And all of this is kind of built into your whole experience. So I said, “Yeah, that would be cool.” I don’t think either of us had any idea. I think he had some songs ready. [Mark Gane]

The next member was Martha Johnson — not an OCA student, but Millar’s former OTP! bandmate now fresh from the Doncasters with her Ace Tone organ. The others liked its eerie, reedy sound, but it was agreed the Ace Tone would rarely stand alone, given the effects at Millar and Gane’s disposal. Martha brought in bassist Carl Finkle, who was unengaged after the Country Lads broke up. Others filtered in and out of Millar’s apartment that summer, including fellow OCA students Andy Haas (originally from Detroit), Martha’s brother David, her ex-husband John Corbett, and David Clarkson, contributing sounds and process to the unnamed project at a measured pace — a contrast to the rapid proliferation of QSW bands in that Crash ‘n’ Burn summer.

Mark and Dave were perfect, musical experimenters because they had — and Andy Haas, as well — a really open attitude towards music. They had actually more experience playing than any of the guys I had played with to that point in Toronto. And so it was fun to get together and see, like, what we were going to put together that’s not just three chords, you know, and 4/4, something that’s 160 beats per minute or something like that. So we had a lot of fun for a few times, and I liked playing with them. [David Clarkson]

Again it wasn’t the Muffins at that time; it was quite a while later that it became the Muffins. But it was just a bunch of people getting together trying to see about putting a group together… We did these sort of speakeasy kind of things, I guess might be the the best way to describe it I guess. We did a few of those things, we opened for other people, stuff like that. [Carl Finkle]

The opportunity to play the Halloween show at the OCA auditorium prompted two decisions for a new drummer (Tim Gane, Mark’s younger brother) and a band name. The latter would be David Clarkson’s final contribution to the group:

We had been having some beers at the Beverly Tavern, which is only a block away from the school, and it was a kind of hotbed of, you know, OCA punk bands, Toronto punk music at that time… I think we were probably talking about the importance of having a great name that stood out, one that would distinctively cut across and be a critique of these punk names like the Viletones and the Ugly. So we were trying to think what would be like the complete antithesis of this black leather band name. And I think it just came out of my head… I think it was extraordinarily useful at the beginning. Because that is the most foolish name I’ve ever heard for a band, you know? You know, who in their right mind would call themselves the Muffins, you know? Because it’s a feminization of a really masculine pose. [David Clarkson]

Clarkson withdrew from the OCA for a year, but the Muffins’ official debut at the OCA Halloween show went well enough to lead to two dates opening for their friends the Dishes at the Shock Theater in December, then four dates at the Bev in the new year. When Millar dropped out, Andy Haas joined full-time.

I was living with Millar at the time in those rental houses that I was talking about, and the frustrating part was trying to get David to come to the practices at any regular basis on time. And then he didn’t like practicing and didn’t like the formality of it, so eventually he lost interest in becoming a musician or anything. He was more of the — I know I keep using Eno as a bit of slang, but he was sort of the Eno part of the band. [Carl Finkle]

Well, Millar quit because he hated playing live. And he started doing our live sound, because he was just too nervous. We were all really nervous, but I think he just went, “Oh man, I can’t; this is just too much for me.” So I remember it was on the annual bus trip to New York every maybe March, April. It was on the bus, and we were all on it, and Andy was there… I have this memory of us having this sort of fairly serious conversation about Millar. We all knew each other, and I said, “David doesn’t want to do it anymore. Do you think you might be interested?” I think [Andy] was just learning the sax, basically teaching himself. And he would be in the Annex and have himself up against the wall to hear the reflections, and doing all this crazy stuff. [Mark Gane]

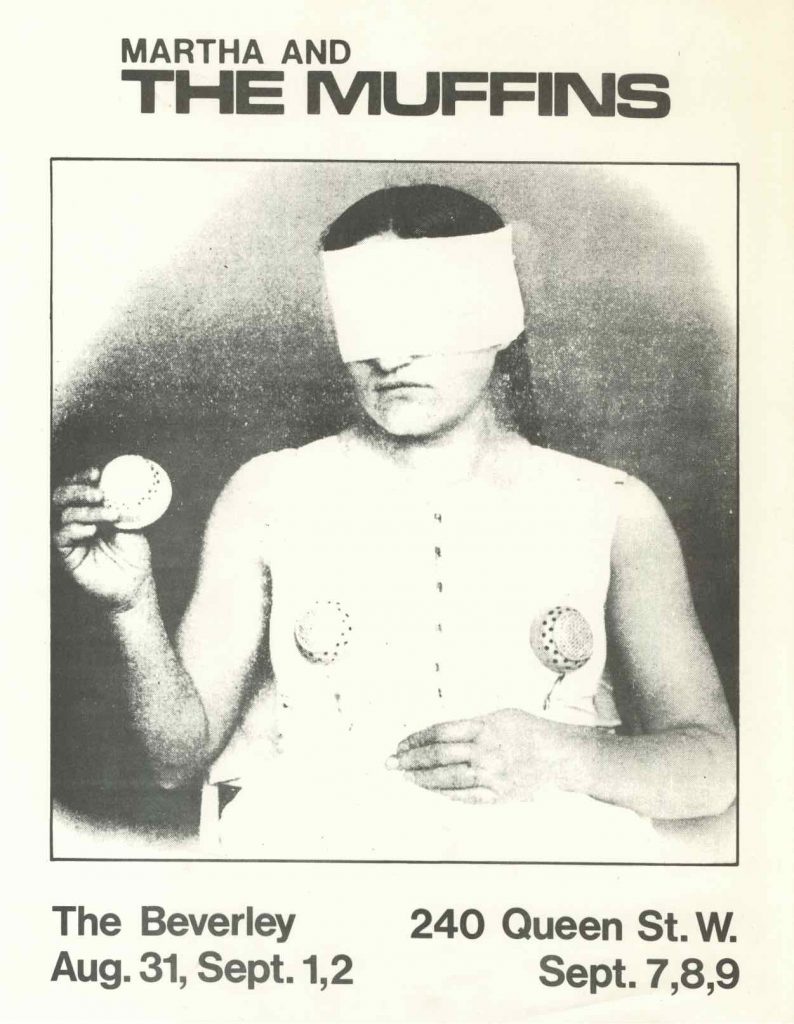

Martha Ladly, another OCA student and Gane’s girlfriend at the time, was added on Wurlitzer organ, cementing the classic Muffins six-piece line-up. Two keyboards, two female vocalists — two Marthas! — plus saxophone atop a tight, melodic trio distinguished the band from even the template established by the Dishes. Here was a real OCA band with three enrolled students bringing to bear sound effects, compositional experimentation, and a gender challenge on the traditional rock format. Even their smartly designed flyers reflected their art school training. At the same time, they were fundamentally suburban (in addition to the two seasoned Thornhill musicians, the Ganes and Ladly were from Etobicoke), with a lyrical and visual commentary that highlighted the suburban framework of so much activity in the QSW.

Downtown wasn’t necessarily family oriented or had young people living there. The phenomenon of repopulating the downtown is due to the artists and the musicians, who all obviously came from elsewhere. They were not downtowners. They were not urban in that respect, so they would be suburban. Suburban within the outskirts, within Toronto — although Toronto is like very residential very close to the downtown — but outskirts like Thornhill, Willowdale, a bit closer than Thornhill. But also from outside of Toronto… So the people that came to Toronto to join the art community came a bit farther, but they came from suburbs as well. So yes, [the new art scene] was a suburban movement that found ironic reference back to their adolescence. You know, their late childhood, adolescence. All these were the signifiers — you know, the late 1950s, early 1960s were signifiers that new wave picked up on. [Philip Monk]

Elsewhere I’ve written in greater detail about the story of the Muffins’ rapid commercial ascent, from a 1978 demo tape sent to Interview magazine to a 1980 top ten hit in the UK, Australia, and Canada with “Echo Beach.” Here I focus on the QSW art scene’s embrace of the Muffins. As 1978 rolled on, the Dishes broke up, the Viletones split up, with Steven Leckie keeping the name and sputtering into a rockabilly pose, and the Diodes battled their Canadian major label to get effective promotion. Meanwhile the Muffins were headlining the Beverley, playing 12 shows there that summer alone.

These occurred in the context of the waning of the Crash ‘n’ Burn generation of QSW punk bands, a story told in Liz Worth’s oral history Treat Me Like Dirt. The local art community would still seek out QSW music for entertainment, inspiration, and socializing, but punk bands had become less its focus. A comparison of two music-heavy issues of General Idea’s FILE Magazine is suggestive. Whereas the Fall 1977 “Punk Till You Puke” issue drew photo subjects and participants from the Crash ‘n’ Burn set, two years later the “Special Transgressions” issue featured a wider-ranging set of musicians (the Muffins’ lyrics to “Insect Love were the basis for one piece) as well as artistic practices that, from a distance, can be included into Toronto new wave.

The art scene’s embrace of a new wave aesthetic is prominent in David Buchan’s “variety show” Fruit Cocktails, a September 1978 event taped for Tele-Performance, a festival of the emerging QSW video art community. Buchan stages lip-sync performances to classic 50s/60s pop for the camera: e.g., his alter ego Lamonte Del Monte croons “Going Out of My Head” in a straightjacket, Anya Varda vamps to “My Heart Belongs To Daddy.” Predictably there are Dishes present: Murray Ball sings a number, while Steven Davey serves as sleazy emcee Red Sublime. The break-out stars of Fruit Cocktails were the Clichettes, whose lip-sync of Leslie Gore’s “You Don’t Own Me” would later be recognized as a milestone in Toronto art.

Like everything good it started out as a joke. Janice Hladki and Louise Garfield and Elizabeth Chitty — Elizabeth and I had been at York together. I think everyone had a slight connection to York, maybe summer dance school or something like that. But Janice and Louise, anyway, we were all at 15 Dance Lab. You know, we were the independent choreographers. Lawrence liked to call us dance workers. People were identifying themselves as art workers instead of as artists or dancers or that kind of thing. There was that political undertone type of thing. And everyone was just in each other’s work, because it was a small interested group of people. So it’s like you would see somebody performing their work, and then you would say, “Oh I’m working on this piece. Do you want to be in it?” So Janice and Louise and Elizabeth and I were all in each other’s work. And then decided that we wanted to be rock stars so we invented the Clichettes. [Johanna Householder]

Pounding their fists on the floor to the lyrics, “Don’t tell me what do do, Don’t tell me what to say…” the Clichettes were subconsciously helping to hammer out part of the foundation for a new woman’s cultural community… Looking back, it can be argued that the birth of the Clichettes coincided with the birth, or public emergence of Toronto’s recent progressive cultural scene. For 1978-79 was the year when the gay community would look for and receive cross-community support in the first court battle of The Body Politic. And 1978 was also the year when Immican, the Regent’s Park Caribbean community organization, emerged publicly as the generator of dub poetry and reggae music. At the same time, the decade-old downtown artist community was about to make a tentative leap into the larger cultural milieu, aided by external allegiances of gender, sexuality and class politics. [Robertson 1986: 11]

So, lip sync: we had no talent. We were dancers. We couldn’t play instruments, but like everybody we wanted to be rock stars. But we were very conscious of the kind of meta level that we were in. People think meta came later, but meta has always been I think part of the art scene, or art thinking. It was obviously a strong feminist statement. We had all been working pretty hard in the previous few years as dancer thinkers. trying to figure out how physical performance could address social political-issues. That’s pretty straightforward. And we also wanted to look at choreography that was disallowed in mainstream choreography, which is basically Motown. So we were really looking to that choreography as a location for our own bodies to present this sexy but controlled, emotional but controlled performance. These are the factors: feminism, Motown, social political, wanting to try to resurrect dance from Graham or even Cunningham. [Johanna Householder]

In 1978, as the Clichettes’ performance proved, cultural criticism could be fun, too, rather than earnestly moralistic, and control of the means of representation could mean a playful engagement with the “oppressor.” [Monk 1998]

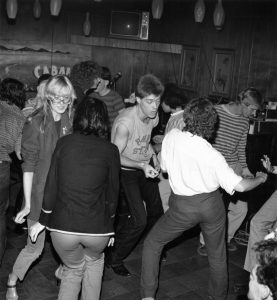

Much of the fun of Fruit Cocktails is the decoration scheme: neon colors, cheap plastic sunglasses, leopard skin, vinyl, shapes and colors that seem to have leaped off a Wonder Bread bag — all retro signifiers from the North American pre-synthpop new wave aesthetic. As the Clichettes’ performance demonstrates, new wave was an early vessel in which QSW performance and video artists increasingly took up issues of embodiment, gender, and codes of transgression (Monk 2016: 70). Simultaneously, new wave music in the QSW offered artists and on-lookers an environment where women and queer people could find a hospitable and, yes, fun scene. At the Cabana room, the twist contest was one of the more popular events.

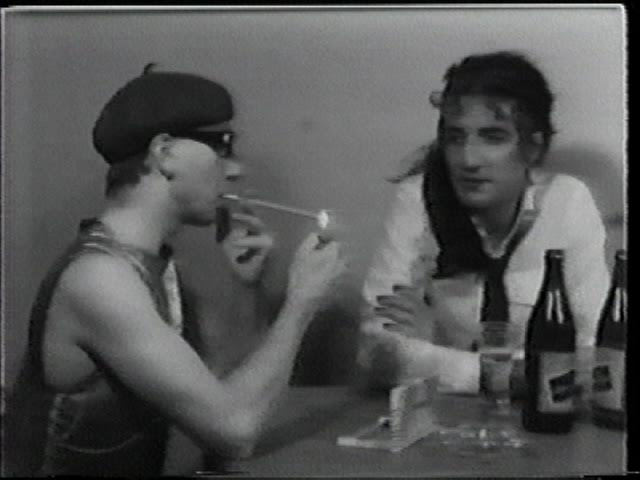

In this milieu, an “OCA band” fronted by two women playing eerie retro keyboards, known to throw in covers of “Telstar” and “Day Tripper” into their set, was bound to be a hit. Martha and the Muffins’ status as 1978-79 “house band” to the flourishing QSW art scene is cemented in Modern Love, a 1978 video by Colin Campbell. Now hailed as a pioneer of video art whose work from the 70s until his death in 2001 prefigured central concerns of contemporary queer studies, Campbell taught film and video at the OCA in the late 70s. Modern Love features Campbell in the lead role of Robin, a Thornhill girl with a boring job as an office clerk, first seen watching a Muffins gig at the Beverley Tavern. There she falls prey to Lamonte Del Monte, portrayed by David Buchan as a louche QSW scenester. The Muffins are heard performing in the background as Lamonte makes his move.

R: What are you doing in Toronto now?

M: Oh I’m working on a TV show. Doing a special. With Anne Murray.

R: With Anne Murray? I really like Anne Murray.

M: Oh yes, she’s had a couple of real big hits, you know. She’s got a hit now, number one in the states.

R: The closest I ever got to show business was my boyfriend said with me being such a tall girl, that if I’d been born in New York City I could’ve been with the Rockettes or something, you know?

M: Well, yeah —

R: But I come from Thornhill.

M: From Thornhill, is that near here?

R: That’s north of here. That’s — Martha’s from Thornhill, too.

M: Really?

R: Yes, but I never knew her in school or anything.

M: I’ve never heard of it. Is it nice? Is it nice up there?

R: Yeah, it’s okay, but I find — I find it more interesting downtown, coming to the Beverly, things like that. It’s just real — you can see all the best groups here, and I really like it.

M: I’ve sort of been looking for, you know, new talent.

R: Really?

M: Oh yeah.

R: What kind of — like, secretary maybe?

M: Well I — I was looking for some of this new wave stuff. You know, I hear this is really popular.

R: Oh, definitely.

M: We were thinking, you know, it’d be good for the Anne Murray special. Something that — something you know, really contemporary, something really modern. I just love everything modern. [Campbell 1979]

Shot on a non-descript set, Campbell achieves a note of QSW resonance (if not verité) by depicting inside knowledge of Toronto’s downtown scene of the time. His representation of Martha and the Muffins as the band of choice — for hapless Robin, and for the video’s conceit — testifies to the Muffins’ status as the new wave band in 1978-79. General Idea’s AA Bronson speaks further to the art scene’s self-consciousness, which suggests the choice of the Muffins was not as casual as it might seem.

In order to be an art scene you have to be able to see yourself as an art scene. In the early 70s magazines such as FILE, Proof Only, Image Nation and Impulse set out to do just that, to reflect the art scene back to itself. Similarly, early Toronto video was usually narrative and usually aimed at an audience of other artists. Artists starred in each others tapes, and a premiere of a new Colin Campbell tape at the Cabana Room was a little like attending the Academy Awards. In this way both periodicals and video aided artists in seeing themselves as an art scene and in representing themselves as an art scene [AA Bronson (1987), quoted in Monk 2016: 21]

Well known (and sometimes criticized by the press) as an art-school band, Martha and the Muffins’ symbolic place in the QSW art community was as much a result of the Thornhill network as it was any aesthetic agenda developed by the art students in the band (none of which, it should be remembered, came from Thornhill). Dawn Eagle, her post-Thornhill artist boyfriend Michael Robertson, and of course Johnson’s high school confidante Steven Davey were just three connections that brought the band into the circles of David Buchan, General Idea, and Colin Campbell — all gay artists pushing the local edge of queer art at a time when Toronto’s feminist performance artists explored similar themes.

Whereas the Muffins don’t appear per se in Modern Love, Colin Campbell evidently saw something in Johnson enough to cast her as the lead in his 1980 video “He’s A Growing Boy – She’s Turning Forty.” Johnson plays Maxine, a tough mid-level corporate manager fretting over her off-screen husband’s affair, which she confesses to Ricky, her young employee who hides his homosexuality from his prying family. Such mature themes, a reveal of Maxine’s stash of male porn, and (by today’s standards) an inappropriate office back-rub surprised many at the video’s June 1980 premiere, not least because the Muffins were known for their disdain of pop music’s traditional romantic preoccupations.

[Colin Campbell] asked me to be in this video, I think, an art video. I was playing this forty-year old woman who ran some office or something — I can’t remember exactly what the part was… He got a young office worker, and somehow he gives me a massage, and it’s kind of sexual — nothing happens or anything. My boyfriend at the time called me up when I was making [Trance and Dance, the Muffins’ second album] at [UK recording studio] the Manor, I believe, to tell me he was so embarrassed when he went to this opening of this video at some place in Toronto. He was embarrassed that I was having this sexual/affair thing happen in the video, and I said, ‘It’s acting, it’s acting! It’s not real!’ I mean, the guy who was giving me a massage was gay; people are hanging around; it’s just acting. [Martha Johnson]

One last episode in Martha and the Muffin’s moment as house band to the QSW art community: Summer 1981 was a significant transitional period for the band. The original six-piece line-up that had achieved a global hit with “Echo Beach” had disintegrated after the departure of Martha Ladly and Carl Finkle, the latter replaced by Jocelyne Lanois. The band was increasingly becoming the vehicle for Martha Johnson and Mark Gane, supported by an adventurous and mostly unknown producer based in Hamilton, Dan Lanois (Jocelyne’s brother). In between apartments following months of touring, Johnson was offered a summer residence at David Buchan’s apartment at 241 Yonge Street (the building that housed the original Art Metropole), a top-floor unit with a long arched window overlooking the busy street. “I think he got a grant, a Canada Council grant or something like that, to go and live in Paris for a summer,” remembers Johnson, so she paid no rent. Further sweetening the deal was the fact that Buchan’s next-door neighbor was a familiar face, Colin Campbell.

Mark Gane remembers that summer as one of the happiest times of the Muffins’ career. He and Johnson enjoyed the freedom that came with committing themselves to recording a highly personal and experimental album — pretty much the opposite of what their intransigent British label Virgin wanted from the band. After three years of playing in the band together, the two musicians were forming a romantic relationship, one that has endured to the present. Needless to say, Gane found himself over at Buchan’s apartment a lot that summer. One night he placed a boombox outside Buchan’s window and pressed record.

I don’t know what it was about Yonge Street then, and it’d be different now, but everybody who had a muscle car and, you know, a reason to beat somebody up or get pissed or whatever would be on that street on a Saturday night. So it’s just jammed with all these cars honking and fights. [Mark Gane]

With a modicum of overdubbing, he made the first sound collage — an old audio technique from his days at the OCA Sound Lab — to go onto a Muffins record. It’s the first sound heard on This Is The Ice Age, the band’s artistic breakthrough, opening the lead track “Swimming,” Its sonic impressionism and trancelike rhythms notwithstanding, the song is evidently more autobiographical than it lets on, telling the story of a surreptitious romance developing between two characters.

The Everglades: Did I mention Colin Campbell’s sequel to Modern Love? Released in 1979, Bad Girls (Parts 1-3) sees the return of the hapless Robin, now fronting her own electronic-dance duo “Robin and the Robots” and trying to get into the good graces of a particularly crass and jaded Susan Britton, proprietor of the Cabana Room. The no-fi music of Robin and the Robots (whose name has a familiar ring, don’t you think?) is a hoot — someone needs to finally issue it as a single, I think — while Campbell milks the character for even more inside comedic fodder than in Modern Love.

While hatching her plans for QSW stardom, Robin seeks the advice of one Steven Davey, seen coming off the stage at the Cabana Room following a set by his own band the Everglades. In real life, the Everglades were a mainstay on the QSW in 1978-80 — a period when the music scene had heated up sufficiently that new wave bands needed the modifier “OCA band” less and less. Plying hard rocking new wave behind Davey’s droll lyrics, surprisingly serviceable vocals, and rhythm guitar, the Everglades initially included Glenn Schellenberg (also from the Dishes) on keyboards, Brad Townsend on bass, and lead guitarist Michael Brook, then sidelining from his own band Flivva plus a day job as administrator of the A Space video lab. Old Dishes saxophonist Michael Lacroix also had a brief spell in the group.

As was the case for most new wave groups on the QSW, nothing really happened for the Evergrades outside the scene. The band landed two tracks on the recorded soundtrack to the documentary The Last Pogo, the name given to the final nights in late 1978 of the Horseshoe Tavern’s as a punk and new wave venue (under the booking of “the two Garys,” Topp and Cormier), although they didn’t actually make it into the documentary itself. Towards the end Davey shuffled the Everglades’ line-up to bring in two Thornhill comrades, John Corbett and Chris Terry, as well as local music critic Kevin Kennedy.

E-static: A virtually un-Googleable group that apparently left no legacy behind, E-static was the vehicle for OCA student Matt Harvey and a number of familiar suspects : Glen Binmore, John Corbett, and Chris Terry.

That was kind of an attempt, partially on my part, partially on Chris Terry’s part, to — I don’t mean this in a harsh way — but to sort of break away from working with Steve Davey. We had spent so many years doing that, we just wanted to put our own band together. So we pulled in Glen Binmore, because the Cads had broken up by that point… and Glen brought in his cousin Blanche from the suburbs, nice Jewish girl, who was just, like, freaked out, like, “Who are you people?!” But you know, she was game, and she played some stuff and wrote some songs. And we played a few gigs like that. [John Corbett]

Again, a different sound: we were kind of exploring that alternate singer-songwriter stuff that kind of marked the new wave. That was good for about a year, maybe a year and a bit. Again, we did some great recording. I was just listening to some awhile ago. We were all trying to make something go of it. That fell apart. [Chris Terry]

The Paysley Brothers: Murray Ball (vocals), Scott Davey (vocals, guitar), Niels Dahl (bass), Bruce Moffat (drums). After briefly playing a spell in the band for Sherry Kean, a singer carving a solo career out of pop group the Sharks, Scott Davey started up a band with his friend Niels Dahl, the Dishes former soundman who had previously played in Drastic Measures. Describing their sound, Davey says, “Picture the Everly Brothers singing the early Animals, Yardbirds and Motown.” Dahl secured drummer Bruce Moffatt via singer Mary Margaret O’Hara, who was dating Dahl and had previously played with Moffatt in folk-rock favorites Songship.

And then [Dahl] drowned. And I went, “Screw it.” It’s like, oh my gosh dude, we’re all ready to play, and a guy who was really super important, like, drowned, you know, in a canoe up here in cottage country up here in Canada, in the same canoe as Ken Farr, who was our bass player in the Dishes. He fell out of a canoe and sank to the bottom. Actually he had a seizure. He had a seizure. Fell out of the canoe and died. And so I stopped. And that’s when I joined the family business, ‘cause my family’s in the publishing business — you know, as a wholesale business in publishing; we sell books to public libraries, is what we do as our family business. And I took that over and I’ve run it for thirty years with my brother. [Scott Davey]

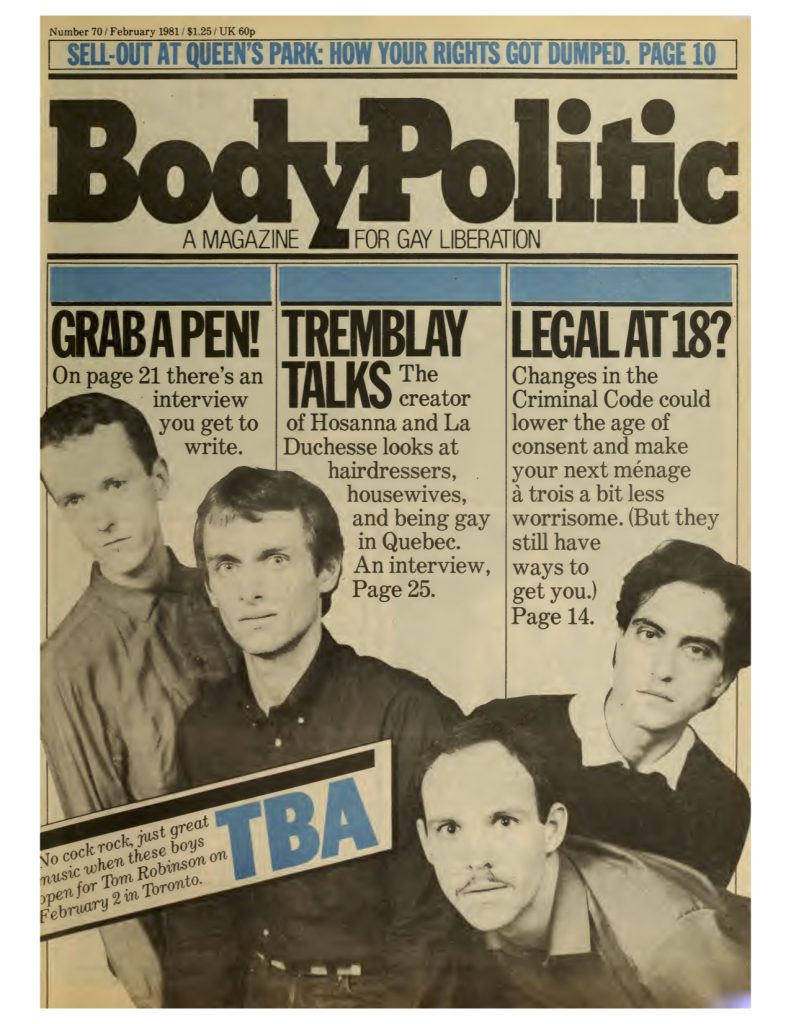

TBA: After leaving the Everglades in late 1979, Glenn Schellenberg formed his own group, TBA, which as much as any other band helped shift the sound of QSW from new wave’s initial guitar/sax format into a full-fledged electronic pop phase. TBA included additional keyboardists Paul Hackney and Andrew Zealley as well as drummer Steven Bock. A band comprised mostly of queer musicians, TBA addressed themes of gay identity and politics in their lyrics. A 1981 cover story in Body Politic (Toronto’s most important gay and lesbian publication of the time) reported, “Basic to much of their material is a clear-sighted look at social reality and a sense of the vulnerable yet undefeated position of the individual in the world.” Way ahead in Canadian pop for expression of gay themes, TBA landed a gig opening for the Tom Robinson Group (the British group that recorded the anthem “Glad To Be Gay”) and played NYC venues a handful of times.

By 1982, when TBA recorded their single “Love Across The Nation” and a self-titled EP, the band’s line-up had changed: Diane Bos had replaced Hackney on keyboards, Brian Skol took over the drummer position from Bock, and guitarist Glen Binmore (formerly of the Cads) made it five. Yet the band was running on fumes at this point. By 1982, Canadian major labels continued to come up short in terms of breaking QSW bands. Local groups often recorded music on independent labels (TBA put theirs out on Fringe Product) and sometimes landed it on “new music” playlists at CFNY or CHUM, but most struggled to develop a base outside of Toronto. It was difficult for bands to graduate past the day-job stage, and TBA’s Schellenberg had one of his own, as second keyboardist for Martha and the Muffins.

While promoting their second album, 1980’s Trance and Dance, Martha and the Muffins were weathering a difficult patch. After Ladly, Finkle, and brief replacement keyboardist Jean Wilson had left the band, saxophonist Andy Haas and drummer Tim Gane were becoming uneasy about their place in the group. Yet there was still commercial momentum with the band. In February 1981, “Echo Beach” won a Juno Award (Canada’s version of the Grammys) for single of the year (technically, a split with Anne Murray’s “Could I Have This Dance” — the only tie for this category in Juno history). Committed to finishing 20 more tour dates in the U.S., the Muffins drafted Schellenberg — a connection forged from the Thornhill sound and mutual affiliation with the Dishes.

Oh, yeah. I was like early 20s, and they asked me to tour with them. And the next thing, I was flying to San Francisco, I stayed there for five nights, and we got per diems… It was just like that glamorous kind of rockstar lifestyle. I was so wide-eyed. [Glenn Schellenberg]

The recording of This Is The Ice Age began shortly thereafter. A relatively minimalist album — almost half the album is beatless, for instance — the band could lean on Johnson, Gane, Jocelyne and Daniel Lanois for most of the keyboards, with recording tricks (e.g., a mixing board “choir” of individually recorded voices) producing other synth-like sounds. When a fuller, more melodic keyboard was needed, they brought Schellenberg into the studio. His piano on the coda of “You Sold The Cottage” is a highlight of this excellent album.

This Is The Ice Age was released in the fall of 1981, after which more touring required Schellenberg’s services again. With his own band TBA looking to create some momentum out of their forthcoming single “Love Across the Nation,” the pull between TBA and the Muffins was becoming unsustainable, he remembers.

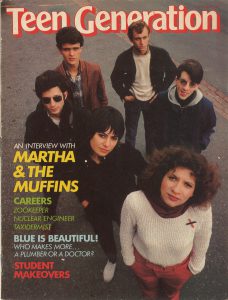

Martha and the Muffins, fall 1981: Martha Johnson, Jocelyne Lanois, Andy Haas, Nick Kent, Glenn Schellenberg, Mark Gane (clockwise from bottom).

[T]here was some New Year’s Eve gig, and TBA had a gig booked at the Cabana Room. It was like very local, but it was cool. And the Muffins had this chance to open for Rush, and they paid my band twice what we would have made at the Cabana Room, and then I got paid well for doing this arena gig with them. God, that was scary… At the time, the Muffins would need me to do their live thing sometimes, just because all their plans were organized around live performance. Then after that gig, when they had to buy me out, they thought, “Oh god, we can’t be in this position anymore.” And I couldn’t, so that ended my relationship with them too. Not in an unfriendly way, but yeah. [Glenn Schellenberg]

(Let me say, the possibility that Martha and the Muffins played on the same bill Rush is so crazy to me, I had to investigate further. In fact, their tour itinerary indicates they performed on December 31 at the Northlands Coliseum in Edmonton, Alberta, with the bands Toronto and Klaatu. Despite Schellenberg’s recollection, neither Klaatu’s own website or this fan-created Rush concert history indicate that Rush performed at this event. If anyone knows differently, let me know.)

TBA dissolved shortly after its 1982 recordings came out. Schellenberg could be found in the mid-1980s playing occasional QSW events with temporary projects antinormal, the Beds (with Tony Malone), and Big Baby. More successfully he turned to composing soundtracks, earning a Genie Awards best original song nomination for “Just Like Schaharazade” (from the 1993 gay-themed film Zero Patience) and penning the theme song to “The Adventures of Dudley the Dragon,” a 1990s children’s show. Schellenberg then went back to school and is currently on the Psychology faculty at the University of Toronto.

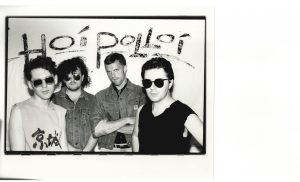

Hoi Polloi: In 1981 Steven Davey formed another band, the electronic dance-oriented Hoi Polloi, with ex-Demics singer Keith Whitaker, fellow Everglade Kevin Kennedy, Steven Gee, and the ubiquitous John Corbett.

By that point I was playing synthesizer bass, and we had a drummer who got poached at some point by a woman named Molly Johnson…. She poached our drummer for a band called — what was her band called — Alta Moda. “High Fashion.” Anyhow, so we ended up using a drum machine and sequencers and things like that, which I would pre-record on a reel-to-reel tape, and I was basically playing synthesizer bass and running the tape machine. And praying to god that everybody counted in correctly, ‘cause if you got lost in the middle of some of our arrangements, you got really lost. [John Corbett]

At the peak of the Human League’s success, Hoi Polloi recruited two female singers Adrian and Andrea. The band’s break-up seems to have been the moment at which Davey and Corbett abandoned their musical plans and shifted their respective career tracks to full-time writer and computer operator.

The Lost Anglers: This is as good a point as any to end the story of the Thornhill sound’s legacy in galvanizing the QSW music scene. By 1982, this cohort of suburban musicians was entering their 30s. If making a living at music hadn’t happened for them at this point, they largely began to reconsider their options. The sound of QSW was changing anyway, giving way to performers like the roots-rocking Handsome Ned and the Caribbean-flavored dance unit Parachute Club. The action moved to new music venues like the El Mocambo and new art hang-outs like the Cameron.

People began to cluck over the decline of street energy and DIY creativity in the neighborhood. Ever the hipster, Steven Davey (quoted in Worth 2011: 366) marked the moment with a specific retail turnover: “The death knell for Queen Street was when the Goodwill turned into Le Chateau in ‘83 or ‘84.” Most others cite 1984, when the music video channel MuchMusic took over the Ryerson Building, located in the heart of Queen Street West.

When MuchMusic got there, you know, [QSW] greatly changed it because they occupied a gigantic building. That occupies, virtually an entire block, so it’s like the biggest thing on the street. But it’s not like you can go in there and hang out there. You know, it’s not like you can go in there and have some drinks, Len. It’s a business! They got security and the like, dude. So you can’t really do that. [Scott Davey]

In turn, MuchMusic’s arrival fueled the commercial ambitions of bands and musicians who were now coming to Toronto at a greater pace than in the prior decade. In a similar way, the downtown art community may have also lost its innocence at this time, if it can be called that.

[In the 1970s] there was this moment where nobody was looking, and the artists weren’t looking to New York, for instance — they were looking to Europe, certainly — but they had the freedom to create an art scene that wasn’t dependent on elsewhere. Whereas the art scene of the early 1980s really once again fell back on this problematic of Canadian art constructing itself elsewhere. So once again look to New York and also look to Europe with the development of the painting scene, the neo-expressionist painting scene in Europe. So I think there are really two distinct, well not distinct communities, but there are two distinct generations. One was a failure and the other was more successful. But both of them went hand in hand in developing the contours of the downtown art community. [Philip Monk]

In 2017, the Thornhill sound plays on in the guise of the Lost Anglers, an all-star group composed of John Ford, Owen Burgess, Ross Edmonds, Chris Terry, and their occasional Etobicoke guest Mark Gane. In clubs on Danforth Avenue or other spots many steps removed from QSW, the Angers play country-rock originals and, from time to time, songs from the old days.

ROAD MAP TO QSW:

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 1: the Thornhill sound

the Thornhill sound

suburban dream

precocious urbanites: the Ross sisters

the starmaker: Steven Davey

the bands of Thornhill

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands

the Thornhill sound leaves home

how art came to QSW

Oh Those Pants! bring the Thornhill sound to OCA

the Dishes open up QSW to new music

punk and art: the Diodes

the Thornhill sound set loose on QSW

the last house band: Martha and the Muffins

sources, citations and updates