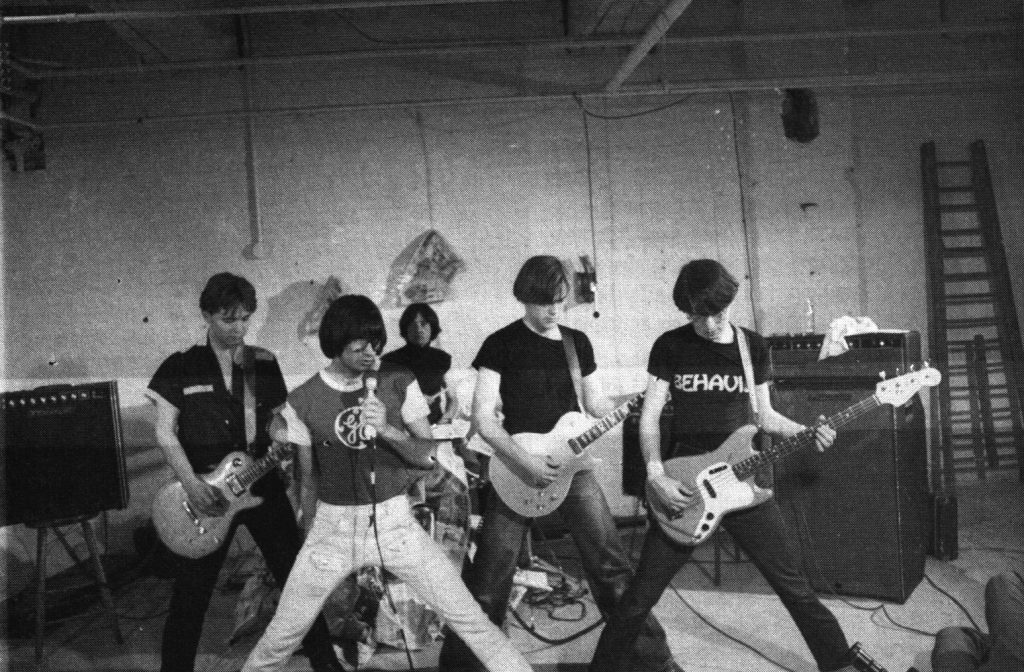

The Diodes: John Catto, Paul Robinson, John Hamilton, Ian Mackay, John Corbett (l-r). Photo by Ralph Alonso: Source: Worth 2011.

[This is the fifth section of the blog post “how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands”]

Once Thornhill got to OCA, you’d have to probably put the Diodes more in that origins, rather than in the origins of punk in general. Because we really come from that OCA piece, you know. [Ian Mackay]

The genesis of Toronto’s first punk explosion, memorialized in its 1977 “Crash ‘n’ Burn summer,” is generally focused on the Viletones, the Diodes, the Ugly, and the Curse. Of all these groups, the Diodes are of particular interest here because of their association with OCA and the QSW art scene. The Diodes were not from Thornhill, but as such they illustrate another ideal type of the “OCA band” scenario that, in my argument, intersected with the Thornhill sound to establish the QSW scene. They’re also associated with a number of other firsts that provide a fuller picture of the QSW music scene.

I can’t do justice to the legacy of the Diodes in this post; fortunately, there are plenty of other sources for that, such as Liz Worth’s oral history Treat Me Like Dirt. Instead, I’ll turn to their origins as the Eels.

The Eels: In September 1976, OCA students David Clarkson and Ian Mackay made a couple of decisions that inadvertently changed the trajectory of the QSW music scene. First, they chose their concentrations in OCA’s Photo/Electrics Arts Department, where their relationship and interests began to cement.

And my third year I transferred into the Photo/Electric Arts department, which was influential on a lot of us. It was dedicated to video electronics, music synthesis, cybernetics. This is all, you know, a brand new department. So I became very, very interested in software and hardware. [Ian Mackay]

I did a sort of split program between Photo/Electric Arts and Experimental Arts, which was what they called contemporary painting… The Photo/Electric Arts aspect of it was more kind of critical theory area, that was founded on kind of a philosophic or communications theory that Marshall McLuhan had been writing about. He, by the way, had his tenure at the University of Toronto, which was literally two blocks away from where I was studying. So I would go up there; he had a carriage house, the McLuhan Center, and I would go up there and kind of listen to some of the workshops and discussions that he would do. And the Photo/Electric Arts program was taught by a number of the faculty there who had studied with McLuhan. So it was underscored by a lot of his ideas into media and perception. And a lot of it was talking about the coming digital age, the coming electronic age, information age, that we were going into. So it was kind of predicated on a situation that hadn’t quite arrived yet. Of course, right now we live with it everyday, so it was an odd kind of prefiguring of that. [David Clarkson]

Second, Mackay skipped the Ramones’ first concert in Toronto, but his roommate, the Finland-born Harri Palm, went with Clarkson. Like so many others in the audience — as in cities over the world where the Ramones played in those early days — Palm and Clarkson came away buzzing with momentum to start their own band. Of course, as art students, Clarkson and Mackay couldn’t just jam a group into existence without first developing an aesthetic agenda.

We were studying kind of contemporary art, and you know, looking at the sculpture of Richard Serra, for example. And we had this idea: we wanted to create a wall of sound, but we wanted to do it using the influences of pop art. And so when the Ramones came along, it was kind of like the perfect solution. You know, get up there on stage and be a punk rock band and project this wall of sound, sort of, and consider it music and sculpture — sort of this hybrid. That was the idea as third year students; that’s kind of what we were thinking. And the Eels were actually born out of that, sort of as a conceptual nod to pop art and contemporary sound sculpture and, you know, how would you blend, hybridize this sort of thing? And then I think it was also secretly stoking our own egos, too. But, you know, none of us were admitting to that, I guess. It was just a lot of fun, too. [Ian Mackay]

A band was put together: Harri Palm on guitar, David Clarkson on bass, another OCA student Rob Rogers on guitar, and a drummer from around town, Bent Rasmussen (who previously played in BBC, a trio also featuring John Hamilton and future Viletone Chris Haight). Ian Mackay worked the sound offstage. No recordings exist of the Eels so far as know, probably because the group played at best three gigs in the last half of 1976. (The former Eels have been hazy on the exact number in interviews with me and others, with estimates ranging from one to three gigs.) The band debuted at the OCA auditorium, opening for Oh Those Pants!

A lot of the songs were improvised and spontaneous. We kind of re-thought the pop song so that it only was choruses and then this jammed instrumental part and then a bunch of the same choruses. We did away with verses and things because we were in such a rush and they seemed kind of extraneous. The lyrics were something like, “Television, television, watch you every day, television, television, nothin’ more to say.” [David Clarkson, quoted in Worth 2011: 42]

I’ve had difficulty dating the Eels’ other performances, although John MacLeod says he remembers the Eels’ final performance — a November 1976 gig at the OCA auditorium featuring the Silverleaf Jazz Band (a still-operative Toronto jazz ensemble), the Country Lads, and the Eels — because this was where he discussed forming a new band with Harri Palm. In any case, the Eels dissolved with evidently little acrimony.

Well, we couldn’t get our drummer to stay with us, because he wanted to go and play something more serious, more jazz-like. And I wanted to do something a little more I think formal, like, write the music down before we started to play it, [chuckles] instead of saying, “Okay, first we’ll do, like, a ten minute thing on A and E. And then, look, we’ve never done a song with only one chord in it, let’s do that for fifteen minutes, you know?” That’s the kind of sentence we would have for Eels. I wanted to try my hand at more writing and that kind of stuff. So I went that way. And Harri I think wanted to do stuff that was a little less blunt and had a little more soul, so that’s how he ended up playing with G-Rays, and how I ended up starting the Diodes. [David Clarkson]

The Diodes: This new band formed in late 1976 around the OCA trio of Clarkson (bass), Mackay (guitar), and John Catto (guitar). Their institutional connections let them access a number of resources and skillsets that gave crucial momentum for the band. First, although singer Paul Robinson was actually an art history M.A. student at York University, Mackay recalls he organized an event at OCA.

So I met Paul when he brought the sculptor, Anthony Caro, to OCA to do a lecture. And Paul was the curator of the York gallery up there at the time, I believe. And Paul was playing Ramones on an FM radio or on a tape player at the reception, and David Clarkson and I rushed up to him and said, “God, you know the Ramones, this is amazing!” Because we didn’t think anybody else knew the Ramones except the people who had gone to the show. [Ian Mackay]

Second, the very first rehearsals (which Eels drummer Bent Rasmussen was around for) took place at OCA’s Sound Lab, where David Millar and his friend Mark Gane could also be found. Messing about with the future Diodes didn’t exactly count as studying, but Clarkson’s college job let him find a way around that.

We were rehearsing around the school because I had the keys. By that time I was working on security at the school. That’s how I paid my way through school. I worked in the pub and I worked doing security. But security at that time meant you just — I had the keys, I had to turn off the lights when everybody left. And basically I just worked in my studio until the time it was to close up and kick everybody out. But I had the keys, so we could go in, like, after hours and stuff. We’d set up our equipment in some of the out buildings of the school, you know, in the warehouses there. And that’s where we rehearsed throughout the fall of ’76, and we wrote, you know, a whole bunch of songs. [David Clarkson]

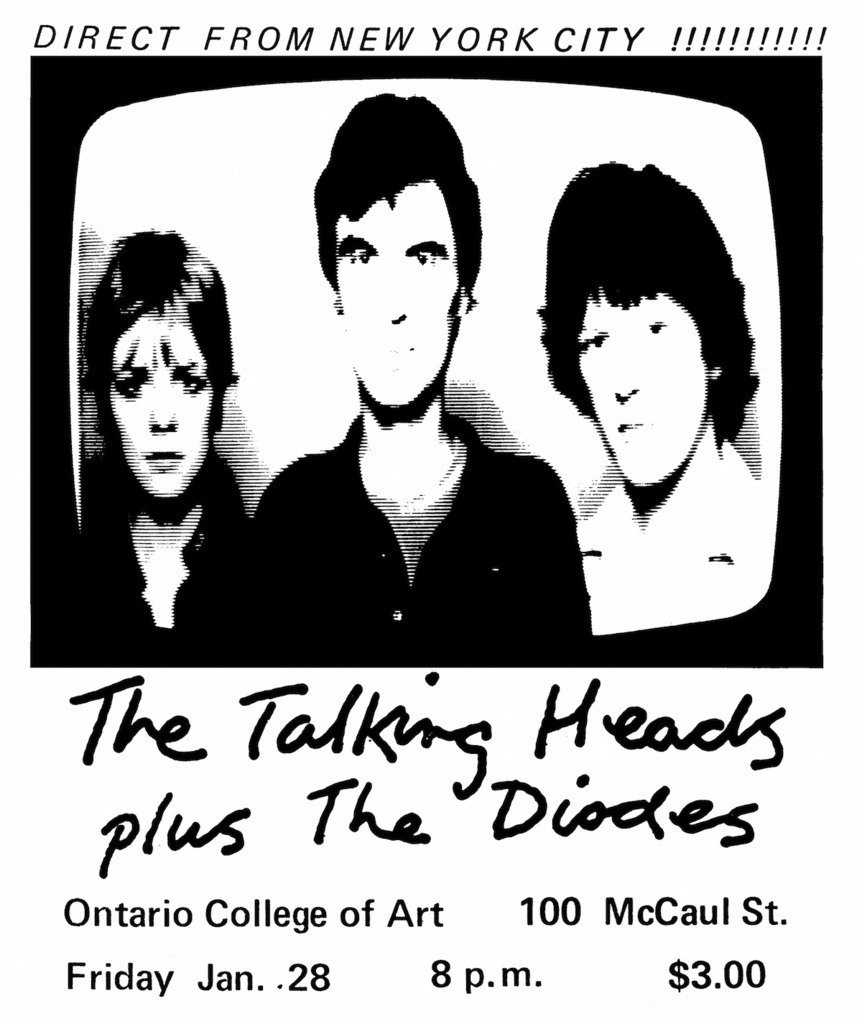

Third, Clarkson and Catto sat on the OCA student entertainment council, which opened the door to an auspicious formal debut for their band. On January 27, 1977, the Talking Heads came to Toronto to play a gig at A Space. The next night they picked up a second gig at the OCA auditorium with the Diodes opening.

We [the Dishes] played with the Talking Heads because David Byrne knew General Idea, because General Idea knew Bob Colacello who was running Interview Magazine… Because we knew General Idea, we were able to play at A Space. Because we were able to play at A Space, we were able to play with the Talking Heads, you know, whose entrée into Toronto initially was through the arts community. That’s the first time they played in Toronto, was at an art gallery, right? [Scott Davey]

My best friend in art college was the person who booked all the entertainment at OCA and we were saying that we really had to do a gig. We found out the Talking Heads were doing a show at A Space… They were a three-piece then. They were doing the A Space show and we were going, “Well, we can co-opt their management and say, ‘Hey, would you like to play another gig when you’re in Toronto and we’ll give you money?’” So that’s what we did. We called them up and sorted it out and of course they went, “Wow, great, we can come to Toronto and do two things.” We booked ourselves in as the opening act. It was a funny gig because everyone from the same period was at that gig.” [John Catto, quoted in Worth 2011: 45]

I recall [Talking Heads] got stuck here for the week because there was a huge snowstorm… Basically they couldn’t drive back when they were supposed to drive back. So they picked up some gigs like at A Space. You know, they were hanging around at the Peter Pan, which was a cool restaurant not far. It was like the first cool Queen Street restaurant. That was started by Sandy Stagg, who was a close friends of, like, the General Idea people, crowd. So they were — Talking Heads were up for around a week and then they went back. But I remember, you know, Tina and Chris being really nice. [David Clarkson]

Fourth, in 1976, OCA established an off-campus studio in New York and began hosting an annual spring fieldtrip there for its students to visit galleries and museums. This quickly became an occasion for musically interested students to hit New York’s nightclubs as well, or even instead; to this end, some snuck their non-OCA friends as well.

There was a trip to New York every year at OCA in March. They’d rent a bus and everybody who wanted to go down would go down. People would be reading fanzines and music magazines from London and New York like NME and Melody Maker and Interview. There was this yearly trip where everybody would go down and go to clubs and see exhibits. So you’d go down and see this stuff and you’d see New York bands down there and it was hugely influential because everybody would come back and say, ‘I just saw Talking Heads.'” [Mark Gane, quoted in Worth 2011: 44]

This would be the second of the OCA New York trips that I went on [March 1977]. Paul by this point had appeared at OCA and was smuggled onto the bus. He tucked himself up on the luggage rack or something, ha ha ha. [John Catto, quoted in Worth 2011: 44]

It was Harri Palm who stowed away in the luggage rack. John Catto is wrong. [Ian Mackay]

The story of the Diodes’ adventures in New York City, which ends with Ian Mackay throwing a brick through the window of a gallery shouting, “Fuck art! Fuck art!” is told in greater detail in Liz Worth’s Treat Me Like Dirt. The thrust of it is that it marked “the end of us being artists, really,” in Paul Robinson’s words — a final nudge toward having a go at making tough rock music versus the intellectualism that was suspect in punk circles. This appears a bit of self-mythology on the part of Robinson, who with Catto has caretaken the Diodes legacy throughout the years. By contrast, at least Clarkson saw the Diodes as a vehicle to pursue an artistic agenda.

Initially, you know, when we started the group, with me and Ian in particular, because we were in Photo/Electric Arts together, and as I said, we were kind of studying these McLuhan-istic ideas of media and perception, we wanted to do kind of what is called a kind of probe into — we call it systems of distribution now, but it was a kind of experiment in publicity and, you know, let’s just start a band. Ian had never played guitar: “Let’s see how fast we can pull these levers” and see [if we could] make ourselves liked or known or whatever it was. So I thought that would be an interesting research project… So we worked really hard on the project and, you know, it started to pay off really, really fast! Like, I’m talking within six or eight months. We played some good gigs, we were getting audience, following, and we’re getting all this stuff in the papers. There’s magazines from outside the country that are wanting to talk to us and take our picture and put it in their magazines and stuff… [But] actually, I always thought of it as a temporary experiment. I didn’t really have an end goal except for to do the research. [Clarkson]

And the most important consequence from the Diodes’ OCA connections was yet to come.

Crash ‘n’ Burn

In September 1976, the Centre for Experimental Art and Communication (CEAC), an offshoot of the Kensington Arts Association, came to Queen Street West. Founded by art theorists Amerigo Marras and Bruce Eves (like OTP!’s Kimmo Eckland, a member of Shitbandit), CEAC pursued a strident Marxist art agenda embodied in their publications Art Communication Edition and (launched in 1978) Strike (see Tuer 2005; Allen 2011). CEAC purchased (allegedly with a wealthy benefactor’s assistance) a four-story building at 15 Duncan Street where a library and archives, a video production studio, a performance space, and a film theatre were installed on the top floors. CEAC rented the ground floor to the Liberal Party of Ontario, and yet still there was room to spare — a basement space that would thrust CEAC into Toronto music history (Worth 2011).

Their critical politics notwithstanding, the CEAC sought in many ways to make their space open to the nascent arts and music activities in QSW. A flyer indicates CEAC hosted two consecutive dates on December 10-11, 1976, from the Thornhill sound: Oh Those Pants! and the Country Lads, followed the Dishes’ “Xmas Wishes” show. Also at some point around this time, CEAC let the OCA Photo/Electric Arts Program host its third-year student exhibit in the basement.

Bruce Eves and Amerigo, they were competing for funding, obviously, for their building, and they were very interested in the social aspects of popular culture. And they knew that David and I were in the Diodes but also doing this mostly video installation and performance work as well, which we did at CEAC in the third year show. Well, shortly after that third year show, Bruce and Amerigo met with David and me and said, “If you guys want to use the space for the summer, you know, we’re gonna be away. What we sort of need is a custodian of the space.” And we kind of agreed. [Ian Mackay]

The six months roughly from the mid-spring to mid-fall 1977 saw the Diodes destabilize, morph, and consolidate. Bent Rasmussen left, to be replaced by QSW rocker John Hamilton, formerly of BBC and the Zoom. The members and manager Ralph Alfonso hatched a scheme for the CEAC basement: they would create a space to support local and touring bands from the punk rock world that was reaching its zenith in the UK and NYC and (with the formation that year of the Viletones, the Curse, and the Ugly) glowing molten in Toronto. CEAC agreed, as a way to have a hand in the youth culture and (they believed) class energy of the punk scene that was appearing alongside the increasingly staked-out art scene.

Thus began the Crash ‘n’ Burn, a weekly venue with a liquor license that launched inauspiciously with the touring L.A. power-pop group the Nerves; the Diodes opened, as invariably they would the whole summer. Over the next eight weeks on Friday and Saturday, the Crash ‘n’ Burn hosted touring groups like the Dead Boys and local faves like the Viletones, Hamilton’s Teenage Head, and other groups from the first generation of Toronto punk. The venue began to attract local press attention, often sensationalistic, and in turn a new audience — young, working-class men from the East End and metro suburbs like Scarborough. Lines began to be drawn between punk and poser. And yet the Dishes also headlined the Crash ‘n’ Burn, while David Buchan held his Fashion Burn runway show there. The venue and its organizers the Diodes were always more open-minded in this “Crash ‘n’ Burn summer” of 1977 than is often remembered.

The Crash ‘n’ Burn was these arty types mixed with these thugs; it was a real coming together. [Anna Borque, bassist from the Curse, quoted in Worth 2011: 87]

On June 8, the Diodes headlined a show at the Colonial Underground. An unanswered request from upstairs to keep the volume down led the bouncers to charge downstairs and beat people severely with pool cues. The “Colonial riot” led David Clarkson to leave the band.

It made me like, “Okay, experiment’s done,” you know. I can see where this is going. Because after we had a number of other gigs coming up, it looked very apparent to me, like, all that’s going to happen is the same machinery is going to be clicking away, and the energy of it is just picking up like inertia, and it’s just going to get bigger and bigger. And so soon it’s like there was, I remember, talk about record deals and signing lawyers and stuff. So as soon as that circumstance changed, where it was gonna go into the public realm in a real social way with literal and legal and, you know, physical consequences, I thought, for me, that’s my experiment. My research is concluded. Any further research is going to preclude me from doing my art, which is, you know, that was the reason I was there. [David Clarkson]

Clarkson was replaced by “John Korvette,” a.k.a. Thornhill musician John Corbett. He played in the band a brief but crucial early period of the Diodes when they worked up their early material (he proposed they cover the Cyrkle’s 1966 nugget, which made their debut album released later that year) and established their punk bona fides via the Crash ‘n’ Burn.

They also had the same kind of streak in it that many of the Thornhill kind of bands did, the sort of weird, slightly sick humor stuff. Do you remember a television show — I think it might’ve been called “Family Affair”? These kids’ parents died in a car accident, and they had to move in with Uncle Bill, and Uncle Bill had a butler called Mr. French. And anyway, years later after all of this, the youngest young lady of the kids committed suicide. She overdosed on pills. So the Diodes, we did a song about that. “Uncle Bill, Uncle Bill, I took a pill. Mr. French, Mr. French, I’m really dense.” So you know, not high art, but hey it was okay, and we were loud. [John Corbett]

On July 7-10, the Diodes hopped in on a series of dates at New York’s CBGB — the Toronto scene’s first splash in the birthplace of punk rock — that were originally reserved for the Viletones and Teenage Head. This act of opportunism fueled the vocal resentments by Steven Leckie and the Viletones for the Diodes’ ambitions, which were only strengthened after the Diodes got signed by CBS Records’ Canadian subsidiary later that year. The CBGB gig also presaged the end of Corbett’s brief membership and the Diodes’ history as a five-piece. Ian Mackay took over the bass guitar slot, while John Catto’s DIY guitar pedals and effects made a second guitarist unnecessary to the Diodes’ sound.

The Crash ‘n’ Burn came to an uproarious end by August 1977, with the media stoking a sensationalistic frenzy about punk rockers and the Liberal Party of Ontario complaining about the damage each weekend. Marras and Eves released a 7” record, RAW/WAR, with musical backing by the Diodes and, on the b-side, a spoken vocal track by Mickey Curse. This represented the Diodes’ first official recording — not at all like the tuneful punk they would subsequently record, but an announcement nonetheless that another “house band” to a QSW artist-run centre had emerged.

The Government: After the Dishes and the Diodes, perhaps the most significant punk participant in the QSW art community was Andy Paterson. In 1976 Paterson became involved with the artist-run Video Cabaret, contributing music to the works of playwright Michael Hollingsworth and feminist performance artists the Hummer Sisters, solo and with the musicians from the band Flivva (about which, see my discussion of The Everglades). The following year Paterson formed his own group the Government to create and realize his accompaniments with his own musicians.

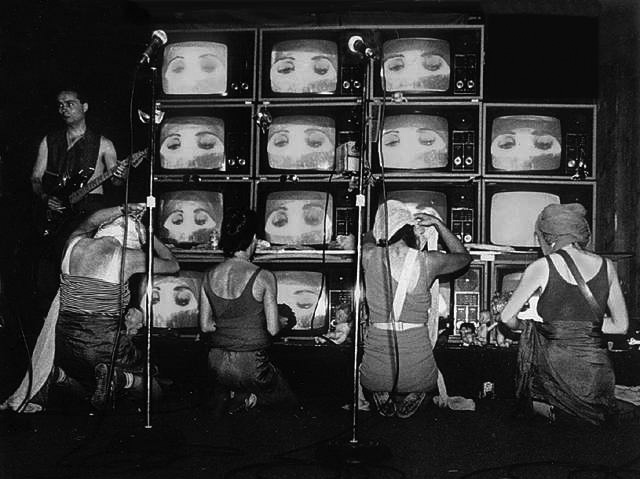

The Hummer Sisters, The Bible as Told to Karen Ann Quinlan. Andy Paterson seen playing in background. From the VideoCabaret collection.

So … I wrote songs, played dirge guitar, and sang. We had a parallel existence as the house band for VideoCab and as an autonomous band, and for a while this was actually tenable. I was at least as interested in soundtrack music as I was in traditional song structures then — I was obsessed with Brian Eno wallpaper, or what Satie called “furniture music”. My main collaborator in the band was Robert Stewart, who played bass, sang, and did some writing. Robert was truly a force of nature, when he was on. He wasn’t a serial or career musician — he was an artist who developed an idiosyncratic style of playing that worked perfectly with his or my or our collaborative songs. Robert was also a great performer – not nearly as self-conscious as I was. The Government had three drummers — Patrice Desbiens from Sept. 1977 to May 1978, Ed Boyd from June 1978 to December 1980, and then Billy Bryans. Billy is a very good funk and salsa drummer, and he kicked some ass into The Government. I mean, I was all theory and not much practice, and I took pride in this. But …even before Billy came on board … the dirge/Goth element had yielded to a sort of scratch funkiness, also with some dub elements. [Andrew James Paterson; ellipses in original]

If the Government’s origins in the Toronto art community is sometimes forgotten, perhaps that’s because the rivalry between General Idea and CEAC has sucked up much of the air in the room that houses the collective memory of the Crash ‘n’ Burn summer. Not helping matters is the perennial slight by art historians given to feminist performance artists like the Hummer Sisters, who are probably best known for their 1982 campaign to unseat Toronto mayor Art Eggleston. (He was handily re-elected, although the Hummers came in 2nd out of a field of 11 candidates.) Thus the Government are more often remembered as a rather idiosyncratic group pushing the musical envelope of Toronto punk in its early days. But Paterson’s stamp is all over the history of Toronto performance, video and interdisciplinary art — the field he continues to work in to this day.

Next – the Thornhill sound set loose on QSW.

ROAD MAP TO QSW:

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 1: the Thornhill sound

the Thornhill sound

suburban dream

precocious urbanites: the Ross sisters

the starmaker: Steven Davey

the bands of Thornhill

how the Queen Street West scene began, pt. 2: OCA bands

the Thornhill sound leaves home

how art came to QSW

Oh Those Pants! bring the Thornhill sound to OCA

the Dishes open up QSW to new music

punk and art: the Diodes

the Thornhill sound set loose on QSW

the last house band: Martha and the Muffins